September 2025

Speculative Fantasy

A series by Nato Thompson

Welcome to the Carnival

Joe Coleman and Gluklya

Nato Thompson, Illustration for Marshsong, 2024

In the second installment of his Speculative Fantasy series, Nato Thompson turns his gaze toward the carnival—not as mere entertainment, but as a dreamlike portal where chaos and ritual entwine.

Welcome to the Carnival unfolds through two distinct visions: Joe Coleman’s obsessive shrines—dense with relics and myth—and Gluklya’s communal pageantry, where garments and stories weave solidarity into public space. An interlude from Scott Gracheff’s documentary How Dark My Love expands the dialogue, featuring appearances by Iggy Pop, Dave Navarro, and Asia Argento, while Coleman’s recent curatorial venture Carnival at Jeffrey Deitch reverberates through the piece.

I had this nagging, strange, creepy dream. It kept coming back. It took place in a carnival: a masquerade bogged down in silted mud. This tarp-laden, soggy mess of a good time called to me from my slumber. I found it alluring, scary, enticing, and unhygienic. There were sideshows, weirdos, broken rickety rides, and few-toothed children. The air sat heavy with fog and smells. All roads were backroads replete with shifty drug dealers, beckoning hookers, and lantern-lit hovels where the voyeurs watched Hieronymus bosch-like freaks with beards and lost limbs. In my hazy waking days, I felt the painted fingernail claws of this place reaching into my life. It inspired a book.

The book stars twins who sleep in a cave during the day and go out at night. They have a cruel master who is away. This master, Marty McGuinn, is away at a place called The Muddy Carnival. This is the carnival of my dreams, and strangely, the place I feel is harkening to us now. If I were to trace the outlines of that dream into the world, I’d find myself among a lineage of festivals that stretches back thousands of years, when the air was thick with incense and roasting meat, and the rules of everyday life were gleefully undone.

Installation view, Carnival, Curated by Joe Coleman, Jeffrey Deitch, New York, May 3–June 28, 2025

Rehearsals for Another World

“During my week, the serious is barred; no business allowed. Drinking and being drunk, noise and games and dice, appointing of kings and feasting of slaves, singing naked, clapping of tremulous hands, an occasional ducking of corked faces in icy water—such are the functions over which I preside.”

—Lucian of Samosata, 160-180 BC

In ancient Rome, there was Saturnalia—seven days beginning December 17th, marking the winter solstice. The city would unbind the statue of Saturn, symbolically releasing the god and all the pent-up desires of the people. The usual order collapsed: masters served slaves at the table, dice games and public drunkenness were not just tolerated but expected, and a “Lord of Misrule”—often the town fool or a lowly servant—was crowned to preside over the chaos. In the Capitoline Hill’s Temple of Saturn, the ritual slaughter of cattle filled the air with a heavy, iron smell. Beyond the temple, the whole city was a stage for unrestrained appetite.

Later, in the season of Lent, came Lupercalia—a fertility rite where young men, dressed only in goat hides, sprinted through the streets, striking women with strips of the hide to bless them with children. The combination of absurdity, sacred ritual, and sanctioned misbehavior was a kind of social alchemy—dissolving norms for a moment so that life could be reimagined.

As anthropologists David Graeber and David Wengrow remind us in The Dawn of Everything, the roots of carnival stretch far deeper than the streets of Rome or the canals of Venice. They trace evidence of ritualized role reversal and collective play all the way back to the Pleistocene, when seasonal gatherings in hunter-gatherer societies could temporarily suspend—or even invert—the norms of daily life. These were not simply cathartic release valves, as some modern sociologists frame carnival, but lived experiments in alternative social arrangements: leaders serving the people, resources shared or temporarily dissolved, sacred hierarchies openly mocked. Play, in this sense, was not a diversion from “real life” but a portal into other value systems—a space where people could test modes of living beyond the dominant order. Seen this way, carnival becomes less an indulgent interlude than a recurring human technology for loosening the ideological traps we build for ourselves, including the capitalist logic that now feels so totalizing.

By the 10th century, Venice had its own signature carnival, a sprawling, water-laced masquerade announced by the Doge. Costumed figures spilled into narrow streets and piazzas: masked lovers, drunken nobles, actors in harlequin diamonds. A Lord of Misrule again presided, while plague-haunted Venetians wove tragedy into the festivities, donning long-nosed death masks that mingled fear and flirtation. Carnival became both an ecstatic celebration and a subtle negotiation with mortality.

Carnival, Curated by Joe Coleman, Installation view, Jeffrey Deitch, NY 2025, Photograph by Genevieve Hanson

Joe Coleman, Stigma/Stigmata: Camille 2000, 2019, acrylic on found triptych, 4.25 x 6 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Andrew Edlin, New York. Photograph by Genevieve Hanson.

Centuries later, in Soviet-era Russia, the literary philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin would give this world a name: the carnivalesque. Writing in the late 1930s under the shadow of Stalinism, he described it as a way of living—not just a holiday—in which hierarchies are inverted, the sacred mocked, and the grotesque body celebrated. Laughter, he insisted, could be a form of political resistance. Bakhtin had seen the promise of revolution curdle into authoritarian control; perhaps this is why his vision of carnival was not mere escapism, but a glimpse of a freer social order.

Fast forward to our scattered now. In place of the Lord of Misrule, we have the strongman President mugging for cameras, the masked agents carting Latino mothers away, the legislative spectacle of commandments posted in classrooms, and a wealthy dead pedophile and his client list. The grotesque is not hidden in sideshows – it is prime-time entertainment. And here in the arts, simultaneously, sensitivities are abounding; the spectacle turns inward. Denunciations on social feeds, people fired for talking about Palestine, artists curtailing their words for fear of offending. Every exhibition should be titled, “Please don’t fire me.” Here too, roles are inverted, the jesters become judges, the audience the executioner. And yet, in both, the inversion does not unite; it fractures. Unlike the temporary commons of carnival, today’s theater offers no shared release. The laughter circles, the masks harden, and the stage becomes a tribunal.

So much violence. So much sex. So few ways to get it all right.

I want to step into the spaces where the carnivalesque still thrives in the art world, in forms both personal and collective. I will begin with Joe Coleman—his love for Whitney, the Jeffrey Deitch exhibition, and the subcultural ecosystem that surrounds them—a vision of the carnival as private devotion, obsessive archive, and dark joy inherited from the punk excesses of the 1980s. From there, I will move to the work of Russian-born, carnival-for-the-working-class hero Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya, otherwise known as Gluklya, whose pageantry unfolds not in a cabinet of wonders but in the streets, drawing on the utopian and theatrical traditions of communist-era street performance. In tracing these two very different embodiments of the carnivalesque, I want to meditate on what it means to embrace pleasure and subversion in public with others, and to examine the strange tension of our moment: an increasingly careful, self-policing art world on one side, a dangerously unrestrained, often violent political right on the other. Ultimately, I will return to the carnival of my dreams—and to Marshsong—to suggest that the carnivalesque is not simply the shadow of society but a parallel landscape, one that is still alive, still seductive, and still terrifying in the ways it calls us to live.

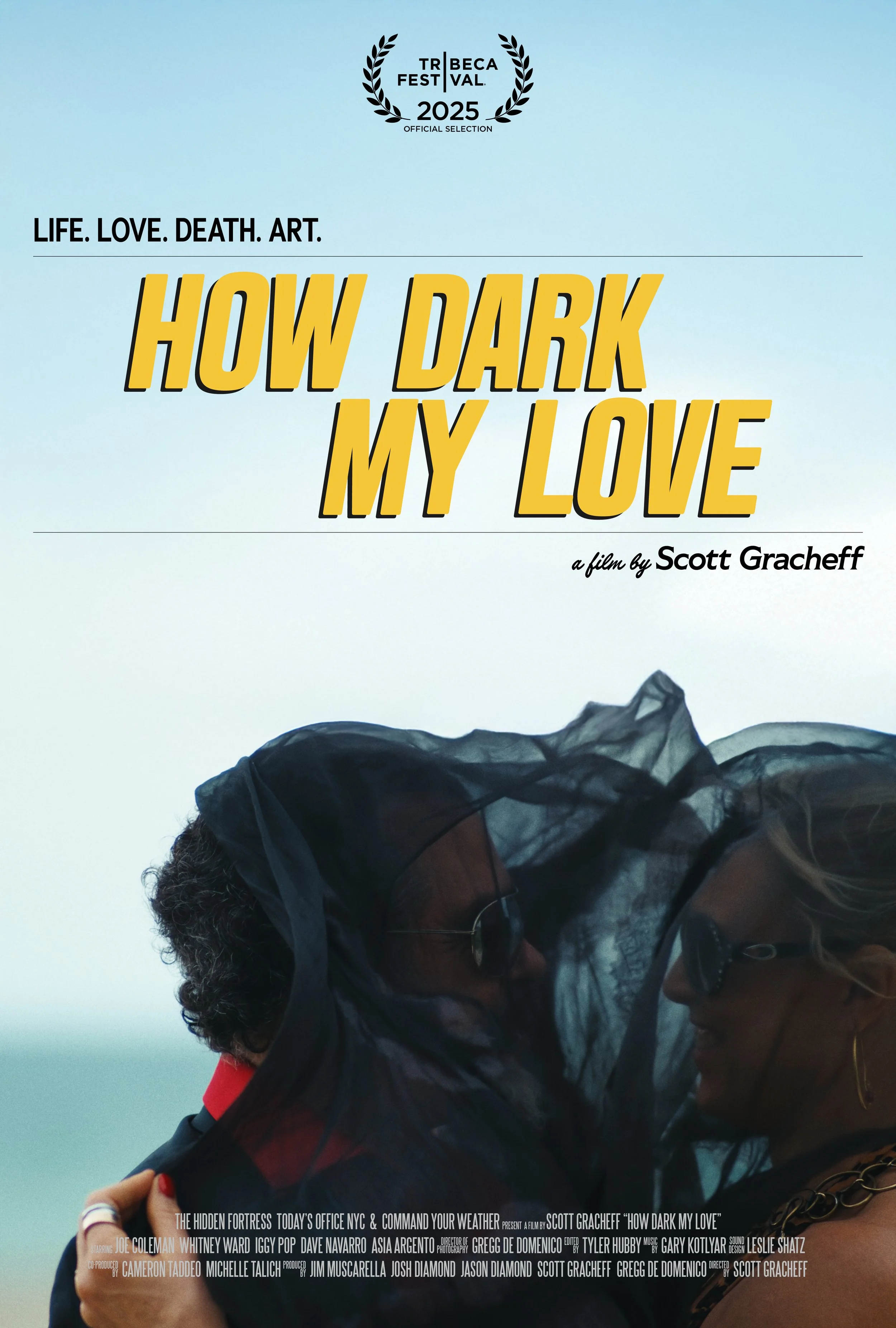

Poster for How Dark My Love, Writer & Director Scott Gracheff, 2025

Joe Coleman and Whitney Ward, Film still, How Dark My Love, 2025, Writer & Director Scott Gracheff

Whitney Ward with Asia Argento, film still, How Dark My Love, 2025, Writer & Director Scott Gracheff

A Saint of the Grotesque

"You're a channel, you're a shaman, and it must be absolutely painful to have all these suicidal spirits, homicidal spirits, suffering spirits go through you, and then there’s love there . . . the spirits need you."

—Asia Argento, How Dark My Love

When I walked into the Joe Coleman show Carnival at Jeffrey Deitch earlier this summer, it felt less like entering a white-walled gallery than stepping into a dense, breathing organism. The air was thick with the smell of fabric, paint, and human obsession. Urges, violence, death, destruction, fetish play, and oddball weirdness pulsed through the space—a reminder that the carnivalesque is not a quaint historical curiosity, but something that still knows how to bare its teeth.

We enter through a gauntlet of spectacle. Just inside the threshold stand two life-size mannequins—a man and a woman—like sentinels to Coleman’s world. The man, bearded and dressed in Poseidon-like attire, holds a trident’s authority in his stance; the woman, crowned and with a cascade of blue hair, radiates a regal, otherworldly presence. Each has a large seashell covering their privates, as if shielding their erotic charge while amplifying it. They clearly reference Joe and Whitney, but not as literal portraits — more as mythologized avatars, refracted through sideshow fantasy. Passing between them feels like stepping into a portal, the air thick with relics, painted signs, and memento mori. Moving deeper into the gallery, the space narrows, drawing us toward the back, where the twin anchor works—Doorway to Whitney and Doorway to Joe—stand like altarpieces. Painted exclusively for a decade between 2005 and 2015 and first shown in Jeffrey Deitch’s Unrealism exhibition in the Miami Design District during Art Basel Miami Beach, they are devotional self- and couple-portraits in the guise of portal-like frames, each packed with miniature scenes, talismans, and fragments of biography.

Encountering them here, in the context of Carnival, they feel less like static paintings and more like sacred thresholds—entrances into Coleman’s private cosmology, where the carnivalesque is not an occasional mask but the very architecture of his life. It is this devotion, and the obsessive labor behind it, that fuels the film How Dark My Love, which follows Coleman’s meticulous process and tangled history, tracing his early years as a taxi driver, his immersion in New York’s punk underground, his struggles with addiction, and his transformation of that chaos into a life’s work built around Whitney as muse and anchor. The film had its world premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival and won the Audience Award for Best Documentary. The film itself becomes a kind of doorway—a beautifully made work that offers a glimpse into Joe and Whitney as extraordinary individuals, where we encounter tensions, tenderness, passion, and depth.

In Doorway to Whitney, one detail stands out like a whisper of something unspoken: her high heel pierces straight through the body of a goldfish, its small form caught mid-swim in a shallow pool of painted water. In the film How Dark My Love, Whitney tells the story behind this—how a client once derived pleasure from asking her to kill small creatures. She speaks of her regret, but also admits he was one of her favorite clients. The admission is matter-of-fact, but the image lingers, unsettling. Watching, I couldn’t help wondering what else swam in those waters, what other dynamics of pleasure and danger were at play. The film hints at complexities it never names, and I found myself circling the same question: how dark is their love? It is not a question I can answer, nor do I want to, but it made me feel that love itself can be carnivalesque—reveling in shadow as much as light, playing at the edges of danger, desire, and control. As Tolstoy reminds us in Anna Karenina, there are as many kinds of loves as there are hearts, and perhaps the darkness is part of the play.

Installation view, Carnival, Curated by Joe Coleman, Jeffrey Deitch, New York, May 3rd—June 28, 2025, Photograph by Genevieve Hanson

The film lingers on Coleman’s earlier life in New York during the 1970s and ’80s, when he drove a taxi much like Travis Bickle in Taxi Driver. High on heroin, he would nod off behind the wheel, wake to wild and depraved scenes unfolding in the back seat, and then head to the club to perform with his punk band The Steel Tips. After leaving the band, he started performing as Dr. Momboozoo. As Iggy Pop tells Joe in the film “You needed to get rid of all of that music syrup.” The performances became increasingly unhinged: biting the heads off mice, setting off fireworks strapped to his body, embracing the chaos and self-destruction that defined a certain strain of ’80s punk alongside figures like GG Allin. In these years, the carnivalesque was not an art-historical concept for Coleman—it was the air he breathed.

Coleman told me about his early years, being a bright-eyed kid from Connecticut who took a visit to NYC and of course, Times Square. He stared up at the burlesque signs that towered over him and felt the energy and vice of this wild fantastical dirty place. This was the early sixties. He recalled seeing Hubert’s Museum at 228–232 West 42nd Street otherwise known as Hubert’s Dime Museum & Flea Circus. He recalled how grotesque and fascinating it all was. And something about vaudeville, sex, transgression, 80s punk and drugs, took Joe down a very specific path in which he found himself to be the main event and also ringleader.

That air fills Carnival. The show’s layout operates like a midway of provocations. Tom Duncan’s kinetic model of Coney Island spins its turquoise Wonder Wheel over miniature sunbathers and mermaid parades, a hymn to the longest-running American sideshow. Raul de Nieves’s glitter-encrusted carousel turns slowly, pastel horses shimmering like sugar hallucinations. A silicone figure of Johnny Eck—the sideshow performer born without a lower torso—stands like a ghost from Tod Browning’s Freaks. Narcissister’s hand-cranked mannequin gyrates with a spotlight between her legs, a mechanical burlesque act.

Nearby, Ghanaian coffins by Theophilus Nii Anum Sowah take the form of fantastical vessels—one cradling a wax figure of Coleman himself, another holding the likeness of Whitney, both in their wedding attire, ready for their funeral voyage. And then there’s Nadia Lee Cohen’s contribution—a holographic display of a young woman caught between wanting attention and recoiling from it, her face and body a high-gloss parody of celebrity self-display. It’s a perfect fit for Deitch’s carnival sensibility: the art of seduction and repulsion folded into the same image, the grotesque hiding in glamour’s mirror.

Coleman’s carnival is an inward spiral: a shrine to private mythologies and obsessions, curated over decades. In this way, it stands in stark yet resonant contrast to the work of Gluklya, whose carnival pushes outward into the street. Where Coleman transforms his personal history into an all-consuming cabinet of wonders, Gluklya transforms collective histories into public rituals of resistance. Both share the DNA of the carnivalesque—inversion of order, embrace of the grotesque, refusal to separate art from life—but their vectors are opposite: one folds the world in, the other unfolds into the world.

The proximity of these two visions points toward one of my central contentions: the carnivalesque is not simply a binary opposition to society, but a parallel landscape, capable of taking radically different forms depending on whose hands it’s in. In Coleman’s, it is obsessive, hermetic, lit by the glow of relics and painted icons. In Gluklya’s, it is porous, collaborative, sewn from the stories of strangers and carried into public space. Both have something to teach us about how to live—and both complicate the notion that the carnivalesque is gone from our present moment.

Gluklya (Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya), Carnival of the Oppressed Feelings/Street Performance Amsterdam, 2017, Photograph by Victoria Ushkanova

Gluklya (Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya), Carnival of the Oppressed Feelings/Street Performance Amsterdam, 2017, Photograph by Victoria Ushkanova

Gluklya (Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya), Carnival of the Oppressed Feelings/Street Performance Amsterdam, 2017, Photograph by Victoria Ushkanova

The People as One Body

The contemporary carnival has become a dull commercial festival that reminds rather [of] a march of the zombies. Bakhtin described the carnivals taking place in the Middle Ages as moments of profound reinvention… where everyone is equal. … To me, the carnival is supposed to give presence, voice and visibility to immigrants and to imagine a better society.” — Gluklya, 2018

On a grey October day in 2017, the streets of Amsterdam filled with the sound of Syrian and Russian folk songs. At the head of the procession, a banner read We Are All Refugees, held high against the damp air. Behind it came a motley assembly: a coat sewn from recycled grocery bags, a dress cobbled together from protest banners, papier-mâché masks with grotesquely oversized mouths. The march began at the former Bijlmerbajes prison, now a temporary refugee center; from barred windows above, a few faces peered down as the parade formed. The air smelled faintly of wet cardboard and coffee from nearby cafés. Every so often, the crowd stopped, and someone stepped forward to speak—stories of bureaucratic limbo, of families split apart, of the ache of homesickness. It was called Carnival of the Oppressed Feelings, and for its organizer, Gluklya, it was not simply a performance, but a shared act of resistance stitched together one garment, one story at a time. The project was born out of a long series of community conversations centered on issues of fair housing and the plight of refugees.

If Joe Coleman’s Carnival was a tightly packed reliquary of personal obsessions —an inward spiral of relics, icons, and private mythology—Gluklya’s carnival works in the opposite direction, unfolding outward into public space and collective action. Both are rooted in the carnivalesque tradition: inversion of order, the embrace of the grotesque, the refusal to separate art from life. Coleman builds an intimate shrine to his own world; Gluklya convenes strangers to imagine a new one. Together, they suggest that the carnivalesque is not a fixed form, but a living spectrum — capable of being both an obsessive, private cosmos and an open-air rehearsal for another kind of society.

Gluklya—born Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya in Leningrad in 1969—traces her fascination with clothing to a deep dive into the subconscious, where garments became a way of navigating both existential and collective memory. Shaped by the devastation of the Soviet Union and the turbulent years of perestroika—when food was scarce—working with clothes became for her a method of overcoming trauma through solitude, imaginative play, and deep concentration. During long summer holidays at her grandparents’ house, she discovered her Aunt’s silk dresses in an old wardrobe. She danced and conversed with them, then transformed them into art objects by attaching fur collars from her grandfather’s coat, naming them The Androgynous and Hermaphrodite Couple. Later, in her St. Petersburg apartment, she hosted salons that brought together poets, intellectuals, and artists. At the height of these gatherings, male poets would joyfully change into her collection of dresses and dance—moments she identifies as the roots of her carnival. Her first performance, at the Assembly of the Untamed Fashion in Riga (1992–93), featured twelve naked men performing swans while wearing her hand-painted silks. From these beginnings, she has carried forward a practice where clothing is not just material but a second skin for memory, vulnerability, and collective transformation.

She came of age during perestroika, a time when the Soviet Union’s rigid ideological structure began to fracture. The underground cultural life that had existed in whispers and backrooms spilled into public view. For young artists like Gluklya, it was a moment of both liberation and uncertainty—censorship loosening even as political and economic systems collapsed. She gravitated toward art that blurred the boundaries between life and performance, politics and play, reflecting the volatile energy of that era.

Gluklya (Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya), Carnival of the Oppressed Feelings/Street Performance Amsterdam, 2017, Photograph by Victoria Ushkanova

Gluklya (Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya), Carnival of the Oppressed Feelings / Street Performance Amsterdam , 2017, Photography : Victoria Ushkanova

In 1995, Gluklya co-founded the Factory of Found Clothes (FFC) with artist Olga Egorova (Tsaplya). The collective staged sartorial performances in courtyards, vacant lots, and cultural institutions, merging the visual language of clothing with performance, installation, and political commentary. Clothing became, for her, a second skin for ideas—a language through which to explore questions of gender, social identity, and power.

The Carnival of the Oppressed Feelings emerged from her ongoing Utopian Unemployment Union—a transnational network of migrants, refugees, artists, and socially marginalized people co-creating new forms of public expression. In this framework, sewing workshops become political laboratories where personal stories are exchanged and transformed into costumes for collective action.

Her current project, Carnival of the Monsters, extends this approach to confront larger systemic forces—bureaucracy, xenophobia, climate crisis, gender violence, and economic precarity. Working with seamstresses and participants in Amsterdam, Central Asia, and Bulgaria, she is developing masks, costumes, and soft sculptures that personify these monsters.

But Gluklya is not interested in simply portraying these “real” monsters. Her approach is to build solidarity among what she calls a cultural community of the weak—care workers, garment workers, mothers, people with disabilities—and to center their vulnerability as a political force. The next Carnival of the Monsters may paradoxically unfold far from the city streets, beginning on the shores of Lake Issyk-Kul in Kyrgyzstan.

She draws from Indigenous traditions to understand how we arrived at the catastrophic climate moment we now inhabit. In particular, she has been inspired by the Kukeri—a pagan carnival in Bulgaria where villagers once mirrored the forces of nature that terrified them. The masks and costumes of the Kukeri were not decorative; they were talismans of transformation, made from grass, sheep’s wool, tree branches, animal skins, and dried flowers. The wearers became as frightening as the fears they sought to ward off.

For Gluklya, the lesson is clear: we must learn to frighten the monsters of our own time, not only by confronting them directly but by inhabiting them—by facing our own fears and fragilities so thoroughly that they can be turned inside out and worn as armor. In Amsterdam, Central Asia, and Bulgaria, she works with seamstresses and garment workers to create masks, costumes, and soft sculptures that embody these monsters. As with her earlier work, the process is as important as the final procession: conversation, labor, and solidarity are sewn into every seam.

Shaped by the collapse of one political system and the ambiguities of what followed, Gluklya’s work carries both idealism and pragmatism. She knows the promises and betrayals of utopian rhetoric firsthand, yet she continues to march, sew, and gather others into her process—insisting that the carnivalesque is not a relic of the past, but a living necessity for imagining the world otherwise.

Gluklya (Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya), Carnival of the Oppressed Feelings/Street Performance Amsterdam, 2017, Photograph by Victoria Ushkanova

A Carnival that Never Ends

“Under, under, under the ground

a place so sensuously unsound

the earth’s rotten center

has never felt better

then when its been scattered and battered around”

Fennel in the book Marshsong

I know these gestures, these energies. I grew up with them. I recall getting face paint at the Oregon Country Fair in the late 1970s, where naked hippies and the smell of weed wafted over our weekend camp. I remember the CalArts Halloween parties of the early ’80s, where installations made from plastic sheeting and discarded furniture were excuses for students to get weird in oddball regalia. I remember early Burning Man in the mid-1990s, when my friends and I dressed up like Jawas and rammed our makeshift Sandcrawler into an orgy called Bianca’s Smut Shack. Yes, there was bacchanalia, there were costumes, there was resistance.

And yet, this isn’t nostalgia for a lost golden age of carnival. If anything, our political landscape is saturated with its logic. We live in an age of memes as mass laughter, body image curated for phone screens, and a buffoon as president. The grotesque body is everywhere: in viral videos, in presidential gaffes replayed as comedy, in the spectacular cruelty of public shaming. This is a political and affective carnivalesque, raw and unfiltered—one that thrives on inversion, ridicule, and spectacle.

Here’s the paradox: while our politics revels in this unruly energy, much of the art world—especially the progressive, institutionalized wing—treads with extreme caution. Fear of offending, of being “problematic,” has fostered a culture of careful speech, even as the world outside is drowning in obscenity, violence, and slapstick cruelty. The jesters have become the judges, the audience the executioner, and the stage a tribunal.

Coleman and Gluklya stand as two very different answers to this tension. His is the dark joy of 1980s punk: self-destruction as theater, obsession as devotion, pleasure and horror entwined in a private shrine. Hers is the utopian pageantry of communist street theater repurposed for the fractured global present: a public rehearsal for solidarity, stitched from the stories and bodies of the displaced. Between them lies a map of the carnivalesque not as a single form, but as a landscape—one that can be as intimate as a locked cabinet of relics or as expansive as a city street.

For me, the carnivalesque is not the binary opposite of reality but a terrain of desire and possibility. If, as Graeber and Wengrow suggest, these integrations of play have always been doorways into other ways of living, then the carnivalesque is not a fossil from a lost golden age but a survival strategy. It offers a way to think and feel beyond the tight circuitry of capitalist realism—not as a utopian escape, but as a rehearsal for values and relations that could exist in the here and now.

It is the dream I keep returning to: the tarp-laden, mud-soaked carnival of Marshsong, its sideshows and broken rides calling to me in the night. Out where the sweat is in the air as the strobe light beckons. Out where the unsettling laughter swirls over a room of cluttered paraphernalia and heavy petting hotel rooms. Where the cops become robbers, the ghettos become sanctuaries, and the dice is rolled eternally. The air tastes like sugar and the museums offer amped up tributes to strange gods. Where Saintlike communists dress up like Gargamel and East Village punks explode. This world, this dream world, beckons through silt and sand. I walk toward its call not knowing if I will come back.

Nato Thompson, Illustration for Marshsong, 2024

Carnival

Curated by Joe Coleman

Jeffrey Deitch

New York

May 3–June 28, 2025

Gluklya (Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya)

How Dark My Love, Scott Gracheff, 2025

Dreaming in Public, Nato Thompson

Joe Coleman is a world-renowned painter, writer and performer who has exhibited for four decades in major museums throughout the world including one-man exhibitions at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, the Kunst-Werke Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin, the Barbican Centre in London, Tilton Gallery and Dickinson Gallery in New York. He was recently featured in the ground-breaking "Unrealism" show in Miami presented by Jeffrey Deitch and Larry Gagosian.

His performance work from the 1980's was some of the most radical of its time, and can be seen in the films Mondo New York (1988) and Captured (2008). The book on extreme performance, Avant Garde from Below: Transgressive Performance from Iggy Pop to Joe Coleman and G.G. Allin by Clemens Marschall, explores Coleman's influence during this pivotal period.

An avid and passionate collector, Coleman's "Odditorium" is a private museum where sideshow objects, wax figures, crime artifacts and works of religious devotion live together to form a dark mirror that reflects the alternative side of the American psyche. His work has been published in numerous books, prints and records.

Joe Coleman was the subject of an award-winning feature length documentary, Rest in Pieces: A Portrait of Joe Coleman (1997). He has appeared in acting roles in films such as Asia Argento's Scarlet Diva (2000) and The Cruel Tale of the Medicine Man (2015). He lives with his wife Whitney Ward in New York.

Natalia Pershina-Yakimanskaya (Gluklya) Lives and works in St Petersburg, Russia and Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Considered as one of the pioneers of Russian Performance she co-founded the artist collective The Factory of Found Clothes (FFC) which uses installation, performance, video, text and “social research” to develop the concept of “fragility” – relationships between internal and external and private and public. In 2012, the FFC was reformulated to the Utopian Unemployment Union, a project uniting art, social science, and progressive pedagogy that gives people from different social backgrounds the opportunity to make art together. Since 2003, Gluklya has also been a co-founder and member of Chto Delat group. Gluklya’s work has been exhibited in Russia and abroad in numerous groups shows as well as solo shows, including Wings of Migrants, Gallery Akinci, Amsterdam (2012); Utopian Unions, MMOMA, Moscow (2013), Reflecting Fashion, MUMOK Vienna , (2013 ), Dump Dreams, Scedhalle Zurich, ( 2013); Debates on Division: When the Private Becomes Public, Manifesta 10, Public Program, St. Petersburg (2014), Hero Mother, Berlin (2016), Universal Hospitality (2016), Vienna; Feminism is Politics, Pratt Institute, NY (2016) as well as Clothes for Demonstration Against False Election of Vladimir Putin, 56th Venice Biennale of Art, All the World’s Futures, curated by Okwui Enwezor (2015).

From 2019 to 2023, in the context of her research project 'Two Natures of Colonialism: Russian and European'/Lives and Work of Oppressed Women, Gluklya visited Indonesia and Kyrgyzstan. Derived from this research she produced a body of work which formed her exhibition titled To Those Who Have No Time to Play. (Framer Framed, Amsterdam, 2022–23).

In 2025, Gluklya was awarded a UK Research and Innovation Network Plus Art Fellowship as part of the Shifting Global Polarities: Russia, China and Eurasia in Transition'. This fellowship will culminate in a new project titled 'Carnival of Monsters’

Nato Thompson is a curator, author, and cultural strategist based in New York and Philadelphia, known for his influential work at the intersection of art, politics, and public engagement. A champion of socially engaged art, Thompson has held a curatorial role at MASS MoCA and was Chief Curator of Creative Time, where he produced landmark projects such as Kara Walker’s A Subtlety, Paul Chan’s Waiting for Godot, and Trevor Paglen’s The Last Pictures.

He is the Founder and Director of The Alternative Art School, an online global platform connecting visionary artists through accessible, artist-led education. His writing has appeared in major publications including ArtForum, Huffington Post, and Art Journal, and he is the author of Seeing Power and Culture as Weapon.

Thompson holds degrees in Political Theory from UC Berkeley and Arts Administration from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. He continues to work with leading contemporary artists and institutions to reimagine the role of art in shaping community and culture.