Susan Chen

Susan Chen is an artist searching for the meaning of home. Through painted portraiture, Chen investigates the psychology of race and concepts of community, immigration, prejudice, identity, family, longing, love, and loss. She takes a strong interest in the lived experiences of her sitters, who are members of the Asian diaspora Chen finds through the Internet and paints via Zoom. Broadly, her work is driven by the political potential of figurative painting to enact social change through increased visibility and representation.

A 2020 Hopper Prize Winner and a 2019 AXA Art Prize finalist, Chen received her MFA from Columbia University in 2021 and her BA from Brown University in 2015. Her work has been featured multiple times in New American Paintings and reviewed by The New York Times, Hyperallergic, Artsy, Artnet, Art & Object, Observer, It’s Nice That, Galerie Magazine, and others. Chen presented her debut solo exhibition, On Longing, at Meredith Rosen Gallery in August 2020.

I Am Not A Virus is Chen’s first solo exhibition at Night Gallery and in Los Angeles. She is currently an artist-in-residence at Silver Art Projects in New York City.

Interview by Heidi Howard

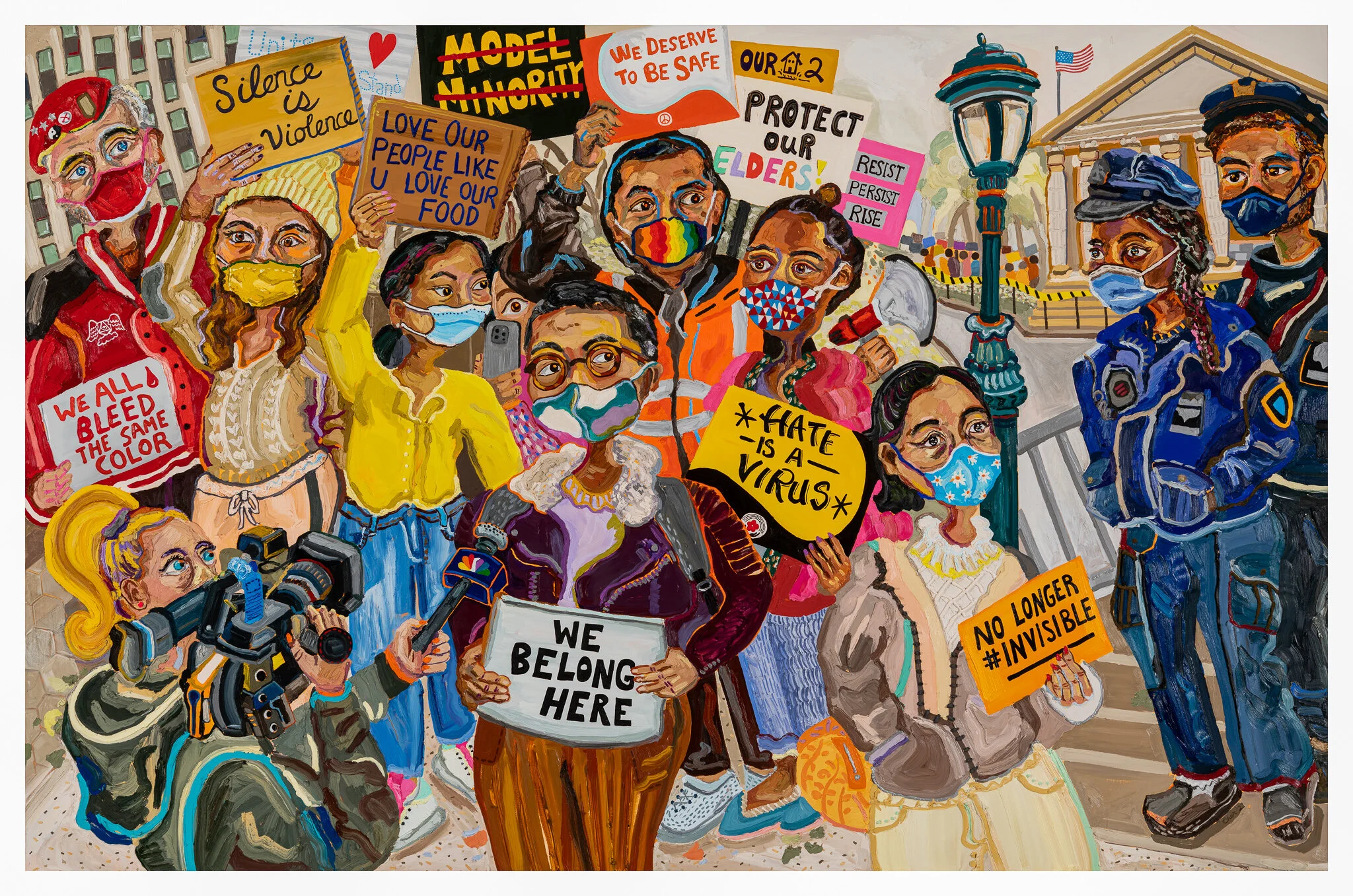

#StopAsianHate, 2021, Oil on canvas, 78” x 120”

I vividly remember the first time we met at an opening at CUE Art Foundation. You came up to me, you knew all about me and my work, and you were very enthusiastic and hopeful. You made a point of introducing me to all the other painters from your class, giving me a short summary of their work. You reminded me so much of myself at the beginning of grad school. I was so happy to be there with other great artists and so anxious to be a part of a community, to make good work, and to show it. I remember you asking me that day about the transition from grad school to becoming an exhibiting artist, and I knew from your positive attitude that you had nothing to worry about in regards to exhibiting soon. It has been a pleasure to see your mindset unfold through painting over the course of the pandemic, especially in the paintings in this show. The pandemic has been difficult, especially for Asian immigrants. Can you talk about your first experiences of the pandemic and how you adapted your practice, how this body of work came about?

During Spring 2020, I was still in my final semester at Columbia MFA when the pandemic hit New York. Because of lockdown mandates, we (the students) all had to evacuate our MFA studios in just a weekend, so the whole situation of losing your studio and having to find a new workspace happened pretty dramatically for my class. None of us knew how long we’d be gone from our studios for, so I remember just taking a box and throwing in all my oil paints and a couple of art books. It’s funny because in a fire, you quickly learn which artist books you must save and which you have to leave behind (sorry Soutine, your book was just way too heavy!!).

I ended up converting my 200 square foot living room at the time into an art studio and painting there during the lockdown months (It was kind of crazy, I wouldn’t recommend it, because then all the paint fumes become part of your kitchen fumes, and it’s just not the best health and safety practice.). During the fall, I transitioned to a garage studio in Connecticut where I made my Night Gallery show.

Because of COVID, I suddenly lost the ability to paint sitters in real life. This forced me to move into self-portraiture pretty much overnight, where I could continue painting a live sitter--that being myself. At the same time, I remember talking to a professor who mentioned he had been threatened at an upstate NY gas station by two rednecks with verbal assaults related to COVID and being Asian. My mom came home from the supermarket one day and told me strangers on the street had shouted at her to “Go back to China.” My sister and I also felt this strange discomfort and embarrassment whenever someone called COVID “the Chinese virus,” which happened frequently at the beginning of the pandemic because the WHO hadn’t declared the official COVID-19 name yet then.

Seeing how the people close to me were affected just because of their racial appearance prompted me to start tracking anti-Asian hate crimes on the internet on a weekly basis. If these events were occurring to people I knew in big cities, I wondered how other Asians were affected in the smaller, rural areas.

For about a year from March 2020 to March 2021, I was reading about these hate crimes pretty much weekly on Google--these were usually reported by smaller news channels but barely covered by mainstream television. After my first NYC solo show, Davida Nemeroff of Night Gallery approached me to do a show, and what I pitched her at the time was that I wanted to do these Zoom portraits of Asian Americans from across the United States. My intentions were to get a sense of how other Asians/Asian-Americans were affected by COVID-related racism, as I had already been reading so much about it for months. But, I was curious about perception (on the news) versus reality, and what was happening locally in different states.

I began with an open call online and invited Asian Americans to submit their experiences during COVID. To my surprise, I received an overwhelming response. I wasn't even sure how to go about filtering who I should pick to paint, because everyone’s stories were just so disheartening and depressing.

Barron Leung, 2021, Oil on canvas, 26” x 20”

Dorcas Tang, 2021, Oil on canvas, 26” x 20”

The first Zoom portrait I painted was of Barron Leung, a Vietnamese American resident in Atlanta, Georgia. I painted him during the week of elections, where he had just gone out to vote that day for Biden (he still had his “I Voted” sticker on). Neither of us knew it at the time, but it turned out Asian Americans in Atlanta made a huge difference in affecting final vote counts in that swing state this past election. I painted him with Georgia peach trees in the background to symbolize his home state, his voting sticker on his shirt, as well as a book: Maria Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet, something he would gift to the world if he could exchange it for negating racism. Barron himself was attacked on public transportation that year because of the increased xenophobia against Asians, so he felt personally invested in my painting project.

I was super nervous to paint Barron because I had never painted someone from Zoom before, or even just successfully from a photograph. But he was such an easy sitter to work with!

I was also super lucky and had gotten myself a snazzy second-hand 4K monitor for just ninety bucks from some gamer on Facebook Marketplace. It turned out to be an awesome monitor that I ended up painting the entire series of all the Zoom portraits from. Barron’s painting led to more Zoom portraits thereafter, and I continued collaborating with sitters I had found on Facebook and community social media groups over the next few months.

Susan Chen working with a sitter from Zoom in her studio, 2021

When you sat for a portrait in 2019, I remember you discussing a desire to expand your practice beyond painting Asians to painting mixed-race couples. This was before you started making paintings of groups of people. I think there was something very exciting that happened there. I remember seeing a big group in your 2019 open studio. Can you talk about the format of painting a group and some of the actual groups you have met through your painting process?

Something I do think about when working in this genre of identity is that you can easily be pigeonholed into painting only certain types of people. I also often wonder if I am perpetuating this kind of “us versus them” mentality, which can also become dangerous. But then I think about the bigger picture, which is that, when you go to museums, there really is a lack of diversity when it comes to portraiture and who you see up on those walls--and it’s all tied with reflecting world history and who is and was in power.

America is a very diverse place when you analyze population groups and neighborhoods, and I think in that sense, America is a unique social setting and experiment when you consider how often race is talked about in the news (we must be reminded that this doesn’t happen often in other parts of the world) and how we all coexist here, racially and socially, in post-colonialism.

I love that in America you can make mixed-race group portraits. Particularly in the aftermath of the Black Lives Matter movement, I also think a lot about “who is allowed to represent who” in America, and “who can protect whom”; this is something I seek to question when painting group portraits of contemporary society. In terms of the format of painting a group, the last two large group portraits I made were #StopAsianHate (2021), which is currently in the Night Gallery show, and Yang Gang (2020). Both reflected real-life events like the Stop Asian Hate rallies I had attended or signature-gathering events for Andrew Yang when he was running for president in 2019. I was inspired by these on-the-ground movements, and after getting a compositional sense of what the painting would look like, I invited local sitters to participate. Each individual came into the studio to be painted over a 4–6-hour period, and they’d only get to meet each other once the painting was completed. I like to think about assembly and assembling people and how painting not only has the ability to portray an existing crew but can also facilitate bringing people together for the first time through a shared cause.

Susan Chen working with sitters in the studio, 2021

Susan Chen working with sitters in the studio, 2021

I also see the group feeling translating to some of the self-portraits you made with objects at the beginning of the pandemic and to many of the portraits in this show. Can you talk about the animacy of the objects in your portraits? How do they become actors?

When you paint objects or still life, you spend so much time looking at that object that you start to wonder if it’s alive (I have on many occasions talked to flowers that I’m painting, and sometimes I feel like they can totally hear me!). It’s like all the characters in Beauty and the Beast: Lumiere, Cogswoth, and Chip!

But I also tend to think about objects and what they look like on the store shelf versus what they represent. How do these products come to be? Who manufactures them? Why are they designed the way they are designed? Who is making these decisions? I remember when I was painting Covid-19 Survival Kit, so many of the items in that painting were packaged in yellow because the color yellow symbolizes caution.

When I was painting Xixi for Sex Positivity (2021), I got to paint period pads, tampons, and birth control pills, and it made me think hard about who initially invented and marketed these healthcare items. Most of these products were designed by a board full of men who often prioritized sales profit margins over the actual health of women. And now in 2021, the recent status of the Texas’s abortion ban, for example, shows how much power and control men still have over what women can and cannot do with their bodies. In general, these objects aren’t just objects. They especially come alive via painting! Each comes with a social history, policies, cultural baggage, movements, stories of humanity, etc.

Xixi for Sex Positivity, 2021, Oil on canvas, 27” x 20”

Carmen & Her Hello Kitties, 2021, Oil on canvas, 26” x 20”

I see Van Gogh all over this show; in the bed in the top left corner of Xixi for Sex Positivity, in the landscape behind Barron Leung. I also see Shara Hughes, Susanna Coffey and Aliza Nisenbaum. However, the paintings are also totally your own! Can you talk about influences and how you remix them?

I always remind people that I entered graduate school with a portfolio of landscapes, and I only figured out how to paint portraits during my time at Columbia. This year, I’ve been thinking a lot more about the artist-sitter relationship, after reading Portraits: John Berger on Artists; Breakfast with Lucien by Geordie Greig; and visiting the Alice Neel retrospective at The Met. I’m also going through a John Bratby obsession at the moment. I’m fascinated by the way he paints everyday items on a kitchen table or how he brings the mundaneness of a bathroom sink to life with paint. I would say Aliza Nisenbaum and Liu Xiaodong are currently working artists with my dream job: working with people and communities. In addition, I want to go into thicker painting the way Tal R, Dana Schutz, or Mark Grotjahn treat their canvases. I’m not there yet, but I am always trying to figure out how to get there next with painting mediums.

Detail: Devon Matsumoto, 2021, Oil on canvas, 26” x 20”

I see two pride flags and some American flags popping out of these new paintings. In your previous work, stripes often functioned as patterns, as landscapes. They take on a different urgency when they become symbols. How do you think about the symbols in the portraits? Do you ask your sitters before you add them, or are they always things they bring to the painting?

I think flags are a big statement to make in a painting. I think for the Asian-American community, the flags in my paintings say so much about desire and wanting to belong. By painting it, it’s almost like saying, “I belong here too.” But, the flag itself also represents how much bloodshed, racism, and colonization took place for America’s birth to take place. Flags are not to be used lightly in a painting. Even the pride flag symbolises a declaration: this is where I stand, this is what I’m for. I think a lot of the symbols in these portraits become manifestos, whether it’s the sitter’s or my own. As the artist, I then become fully responsible for making these statements because of the final painting (even if they’re not my own).

I don’t ask my sitters before adding in symbols, and most of the time their stories are what prompts what gets brought into the paintings. I always set expectations with my sitters upfront, informing them that their painting may not end up looking like them, or the way they expect it to be, and that they don’t get to keep the painting or have financial ties to it. This allows me to protect my creative freedom and to take off some pressure or expectations from the sitter. These days, however, I’m becoming increasingly concerned with the ethics and responsibilities that come with working with sitters, especially when payment is involved.

I’ve actually been meaning to ask you, as I’ve also been very curious. I know you’ve been painting sitters en plein air during COVID. What has that been like for you? Have you noticed a big difference between working with sitters prior to the pandemic versus during?

Well, that same day I painted that portrait of you, we also visited my installation at the Queens Museum, Relative Fields in a Garden. I called it an “expanded portrait,” as it was an expansion of a 50-by-60 inch portrait of my mother in the garden into a 40-by-100-foot wall-painting, which became more of a landscape painting than anything else. I had moved out of New York for the first time as an adult to Amsterdam and I was thinking a lot more about environments and how they affect the body. I am still exploring this, and painting people outside is a wonderful way to integrate flora, fauna, the sky, and more. I love that experience, and the addition of outdoor energy to the paintings. Sometimes there are issues like when it starts to rain, or it is hard to find running water or a bathroom. People have really seemed to appreciate the process of sitting for paintings since the pandemic. I started painting people on Zoom not because I liked the platform or was expecting to make great paintings, but because I wanted to have moments of silence with my friends, space to just relax together and not talk about how we were washing our groceries. The importance of art, especially the slow unfolding and the stillness of painting, I think is very important in this era of high anxiety and ever changing disastrous news. It has always been a part of my project when painting portraits to get us to address these wider environmental problems as a group. The idea is that by being more sensitive towards each other, we can also move more sensitively within our environments.

Oh I love that!! That is such a beautiful and different approach to thinking about portraiture, working with people in this challenging time, and how you can integrate your subjects with nature. In that sense, the flora and fauna become symbols for you too; you as the artist are also taking a stance on a belief. It’s funny because I don’t think either of us would think of our work as political paintings; we’re just concerned about caring for people and for the environment. Yet, portrait paintings, I suppose, have always been political in nature. I can totally feel the slowness in your paintings too, there’s something very calm and delicate about them. It’s got this Raoul Dufy, Matisse drawing-meets-painting quality to it; there’s a softness.

Girl Scouts Honor, 2021, Oil on canvas, 27” x 20”

Sergeant Joy, 2021, Oil on canvas, 28” x 20”

What was your favorite pandemic cooking experience?

We are terrible cooks at my house, but I did get to revisit some epic childhood memories during COVID via the kitchen: eton mess, sticky toffee pudding, pineapple upside down cake, banoffee pie, bread and butter pudding, apple rhubarb crumble, scones, mince pies. Classic British desserts! (I spent my teen years living in the United Kingdom).

Susan Chen in Heidi Howard’s Studio, July 2019

All images courtesy of the artist and Night Gallery