Ray Johnson

A conversation with exhibition curator Jarrett Earnest on the occasion of Ray Johnson: WHAT A DUMP, currently on view at David Zwirner in New York.

Interview by Dan Golden

Photograph of Ray Johnson, October 1984, by Edvard Lieber. Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate.

“For this exhibition I got really interested in some aspects of (Johnson’s) work that haven’t been seen or written about, shifting the focus to how younger queer artists in the 1970s saw what he was up to and ran with it, in their own experiments with sexuality and building a subculture.”

— Jarrett Earnest

Dan Golden: Ray Johnson is an artist I’ve always been fascinated by but one, I hate to admit, who I have also found challenging, especially considering the range and depth of his creative output. Can you provide some insight into Johnson and his work from a 10,000-foot view, so to speak?

Jarrett Earnest: From 10,000 feet Ray Johnson looks very small, but so does everybody. But that height does have the advantage of seeing the shape of his larger networks as they moved throughout the world in the second half of the twentieth century—so it’s actually a great way to see what he’s all about. Famously, he pioneered sending art through the mail, usually with directions to do something to it and pass it along, a practice that was dubbed the “New York Correspondance (sic) School” in the early 1960s.

For this exhibition I got really interested in some aspects of his work that haven’t been seen or written about, shifting the focus to how younger queer artists in the 1970s saw what he was up to and ran with it, in their own experiments with sexuality and building a subculture.

The collages that are mostly known are elegant semiotic works made with incredible precision and care and are almost spare compared to those found in his house after his death in 1995, which he just continued cutting up and adding to for literally decades, so they became almost abjectly dense with references, associations, and additions. With WHAT A DUMP, I wanted to shift the gravity to this later, almost punk, aesthetic.

Ray Johnson, Untitled (Lucky Strike Lucky Strike May), 1979-1987; 1991 © Ray Johnson Estate, Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate

How would you define Johnson in art-historical terms? Do terms like “pop,” “conceptual,” or “avant-garde” apply? Or, are all those sorts of labels too limiting when considering an artist like Johnson?

He was pretty against labels, unless he was making fun of them, like creating stamps for his work that said “FAKE COLLAGE BY RAY JOHNSON.” That’s one of the “problems” that makes him so interesting. Johnson had what we now think of as a ground-zero modernist education at Black Mountain College and as soon as he moves to New York starts making work that prefigures pop art, then performance and conceptual art, even postmodern Pictures Generation stuff; but he never wants to be part of a group, resolutely creating his own context through his New York Correspondance School network, so he doesn’t nicely fit into any of those categories. One reason I think he’s so interesting to look at and think about now is because of how those official stories have more or less given way. We’re actively trying to find new ways to tell the stories of twentieth-century American art; Ray Johnson is a perfect lens for doing that, almost a kind of cipher ...

Ray Johnson, Untitled (Dear Shirley Temple, Geldzahler), 1956-1992 © Ray Johnson Estate, Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate

Ray Johnson, Untitled (Liza Minnelli with Pink Paint), n.d. © Ray Johnson Estate, Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate

Ray Johnson, Untitled (BRUNCH), n.d. © Ray Johnson Estate, Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate

I’d love to hear about your curation process. How did the idea for this exhibition originally come about? What was it like working with the Ray Johnson Estate? How did you select the specific pieces?

Because all the curatorial research was done during the pandemic, it strangely forced me to work in a very Ray Johnsonian way—cold-calling strangers, asking them to go into their storage unit to find an answering machine tape with old Ray Johnson voice messages on it, as one example; or getting someone to photograph specific pages out of a rare catalogue they had and email them to me, as another—basically convincing people to inconvenience themselves for this project. Every single thing in the show, every bit of information I pulled together, had to be located that way, often asking for something I didn’t really even know how to articulate, but casting around until they remember something they have in a drawer or someone else they know I should talk to. In my writing on art, I believe that the language and form should match the art that it’s about; I guess I never thought of a curatorial process following the same edict, but in this case it made perfect sense. I borrowed work from a number of artists’ estates for this show, and they all were beyond helpful. It was humbling the lengths they went to in making this happen, to arrange getting me access to the stuff, so in many ways the whole show feels like a collaboration in the truest sense. I think the past year has made people more openhearted in some ways, and the driving desire for connection at a remove in Ray Johnson’s work made it an ideal subject for the time.

Did you learn anything new or surprising about Johnson during the development of this show?

It began just by looking through the art and ephemera at The Ray Johnson Estate and asking them to pull out the weirdest things they had—stuff people don’t look at or show. Soon I gave the archivist there a list of key words I was interested in and they pulled everything they had that might be related: things like fisting, Arthur Rimbaud, false eyelashes, Greta Garbo, William Burroughs, gay porn, and so on. That initial request brought back sixty boxes of stuff from the estate’s storage. Looking through it, the first surprising thing was how explicitly queer Ray Johnson and his work was—that isn’t something that really gets discussed! But it was undeniable. The second was realizing how involved he was with radical queer artists of the 1970s, like General Idea or Jimmy DeSana, and then I spent a lot of time trying to reconstitute and retrace their friendships and relationships through their art and letters and publications. I wrote a zine to accompany the show that tells all that history I pieced together through interviews and ephemera.

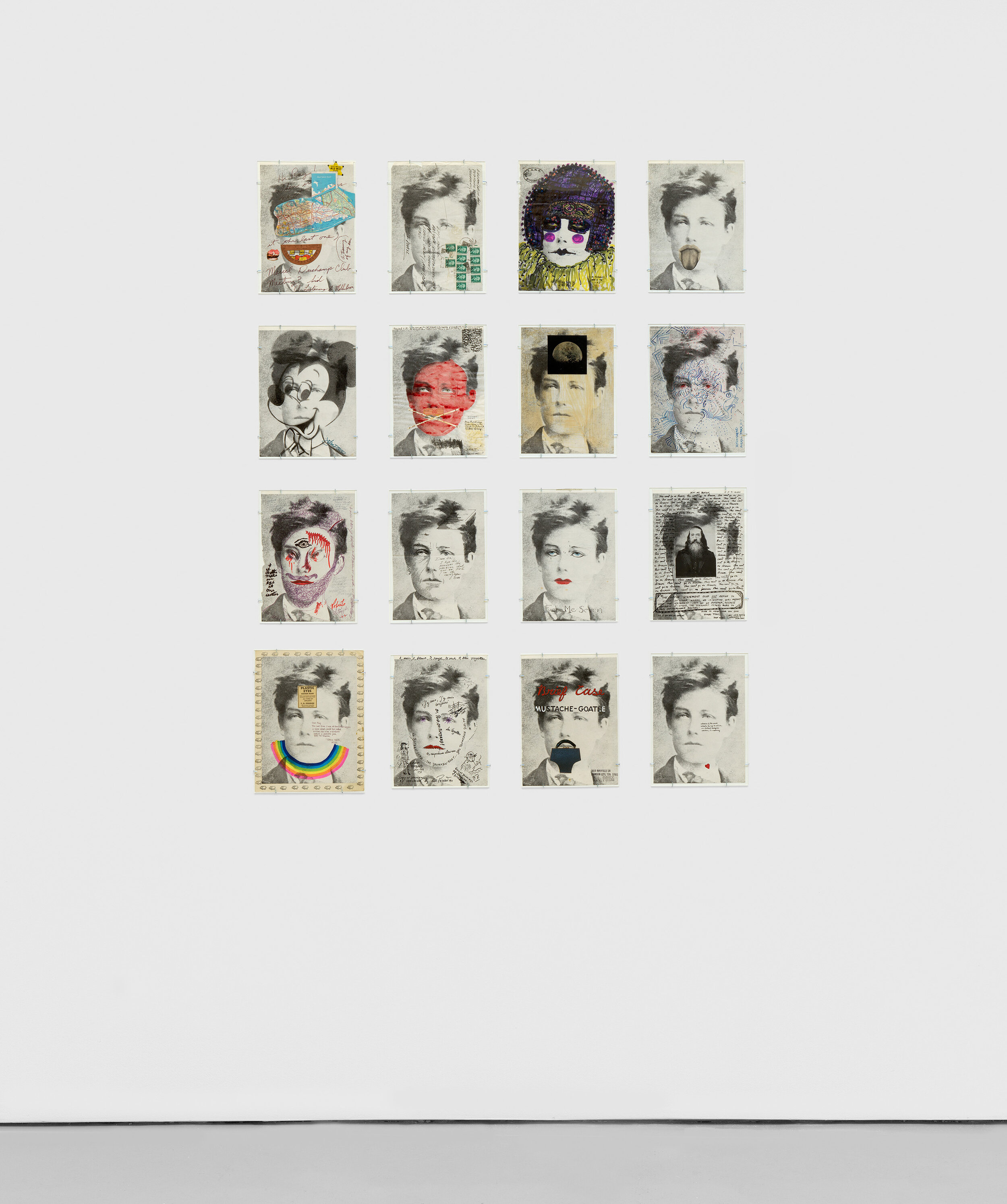

Installation view, Ray Johson: WHAT A DUMP, David Zwirner, New York, April 8—May 22, 2021. Courtesy of David Zwirner

Installation view, Ray Johson: WHAT A DUMP, David Zwirner, New York, April 8—May 22, 2021. Courtesy of David Zwirner

Installation view, Ray Johson: WHAT A DUMP, David Zwirner, New York, April 8—May 22, 2021. Courtesy of David Zwirner

Installation view, Ray Johson: WHAT A DUMP, David Zwirner, New York, April 8—May 22, 2021. Courtesy of David Zwirner

Installation view, Ray Johson: WHAT A DUMP, David Zwirner, New York, April 8—May 22, 2021. Courtesy of David Zwirner

Installation view, Ray Johson: WHAT A DUMP, David Zwirner, New York, April 8—May 22, 2021. Courtesy of David Zwirner

I read that there are some never-before-exhibited works in this show. Can you tell me a bit about what those pieces are, and why this is the first time they are being displayed?

Interesting question. I think in some cases it’s benign neglect, because the kinds of dominant stories about American art in the 1950s and 1960s wanted only a certain kind of art that fit within its parameters. Another reason, inseparable from the first, is internalized and institutionalized homophobia, that museums and academics didn’t want to deal with queerness, and as I said, Ray Johnson is a very queer artist. Maybe an additional facet is that Ray Johnson is a pretty complicated artist—there is just so much work and it’s all layered and it was disbursed far and wide. A lot of the collages that haven’t been seen are his later, more obsessive and heavily collaged works—they are darker, visually and thematically, scatological, filled with sex and death stuff alongside pictures of people like River Phoenix—that do not fit the popular image of Ray Johnson. I’m also including a bunch of stuff that isn’t considered “art”; for instance, some of his clothes that he painted on, like a black leather jacket with neon Mickey Mouse heads painted on it, and a selection of his original silhouette drawings, which have never been shown because they get considered as just patterns for his portrait collages, but I think there is a compelling case to be made for seeing them as a complete conceptual artwork, as he did, calling them the “Silhouette University.”

For those interested in learning more about Johnson and his work in addition to this exhibition, what would you recommend?

The Art Institute of Chicago is publishing a beautiful catalog to accompany their big Ray Johnson show called Ray Johnson c/o, which I think is the single best introduction to all his major themes and projects, written by great scholars as mini-thematic essays. Soberscove Press, also based in Chicago, published the enormously helpful book of Ray Johnson’s collected interviews called That Was the Answer. It’s a fabulous read, like witnessing a free-form performance piece as it unraveled across decades. Last, I would say that Siglio press has been committed to making really good Ray Johnson books, especially important is the selected writing compendium called Not Nothing. Of course, the documentary How to Draw a Bunny (2002) is an art-school classic at this point (that’s where I saw it) and it’ll give a great introduction.

Ray Johnson

WHAT A DUMP

David Zwirner

April 8—May 22, 2021

All images Courtesy of the Ray Johnson Estate and David Zwirner