January 2026

Patrick Eugène

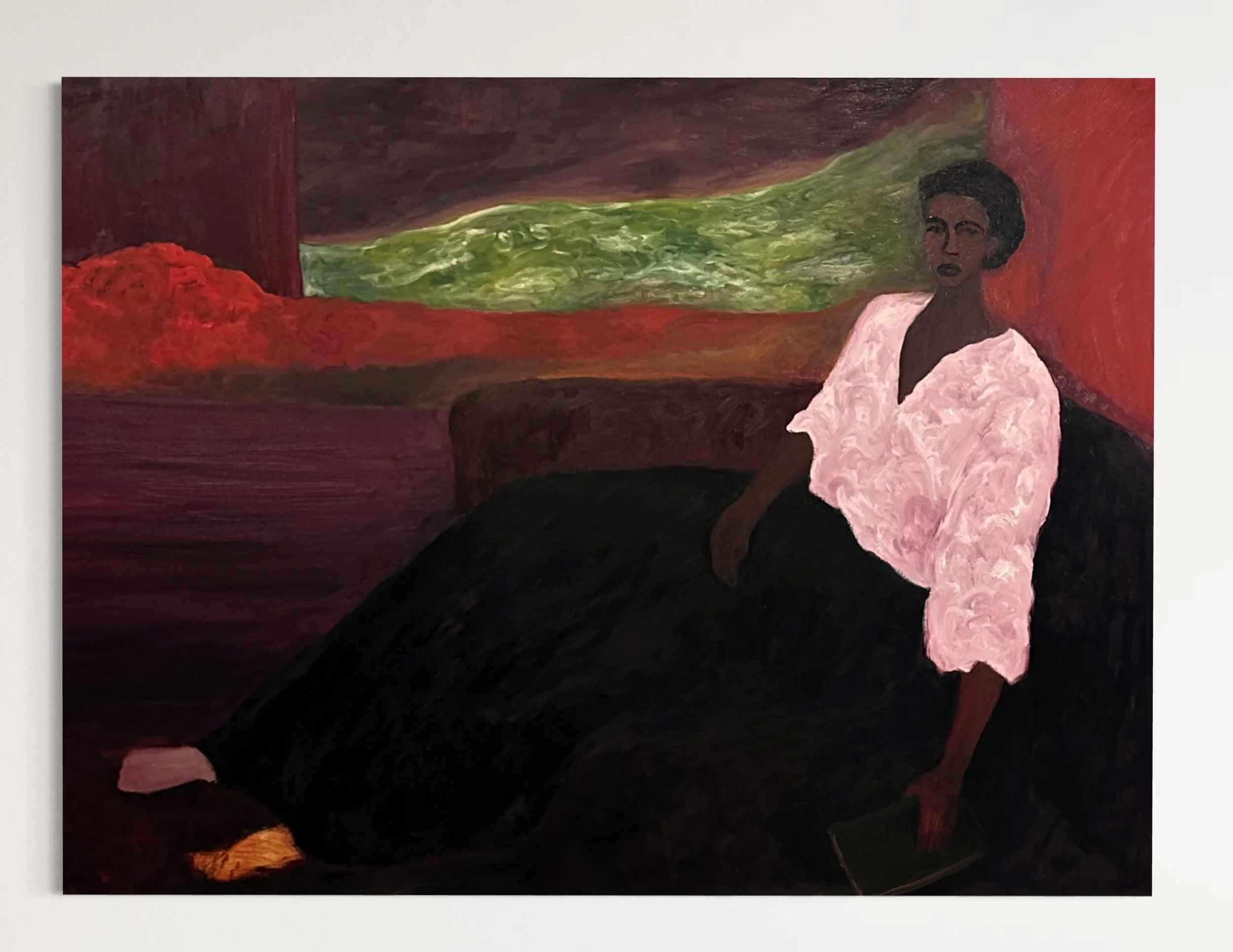

Detail, Waiting on the Trumpet, 2025, oil on canvas, 60 x 72 inches

Artist Patrick Eugène on memory, meditation, and the bridge between abstraction and figuration.

Interview by Dan Golden

DG: Hi Patrick. It’s great to talk with you. From what I’ve read, you work entirely from memory, so I’m curious to hear where your figures originate and what guides their presence on the canvas.

PE: Yeah, it's all memory. We're all flooded with images every day, and they stick somewhere in the back of our heads. I don't want a sitter or photo telling me what to do. I like letting the figures show up awkward, a little off, sometimes not perfectly proportioned. That's where the humanity is. I paint almost like I did when I was abstracting, moving things around, letting spirituality guide it, letting it flow until it feels right.

DG: What inspires you and your work?

PE: Music, always. Jazz is on heavy rotation in the studio. Conversations with my people keep me grounded and thinking. And then there's the weight of the times we're in politically and socially; it all feeds into the work. As a Haitian American, I feel a responsibility to speak to Haiti's story and spirit in subtle ways. Recently, The Sweet Flypaper of Life by Roy DeCarava and Langston Hughes has been pushing me to imagine how my painting could sit in dialogue with their photography and poetry.

Waiting on the Trumpet, 2025, oil on canvas, 60 x 72 inches

Dan Golden: You worked in finance before shifting to painting. Was art always a part of your life in some way? What led you to make that transition, and how did it unfold?

Patrick Eugène: Yeah, I was in finance for a while, among other jobs, just doing what I had to do to make a living. Painting came in as a way to offset that nine-to-five grind. I needed something to balance life out, you know? I'd always been creative- heavily into music growing up, producing with friends, but painting was new. I started in my Brooklyn apartment, just me in a converted bedroom, trying to figure out how to put eyes and noses in the right place. It snowballed fast. I'd lose hours there, forget to eat, just completely locked in. Eventually, it went from a hobby to something I had to do all the time. That's when I knew I needed to give it everything.

DG: What draws you to the figure? Have you always felt a connection to figurative work, or did that connection emerge more gradually through your practice?

PE: The figure was just where I started; it was familiar. But for years, I was deep into abstraction, trying to figure out how to tell stories and pull out emotion without anything recognizable on the canvas. When I moved to Atlanta, I came back to figuration with everything I'd learned from that abstract period. Now, even when I'm painting people, it feels loose, open to interpretation, not locked down or overthought. That tension keeps it alive for me.

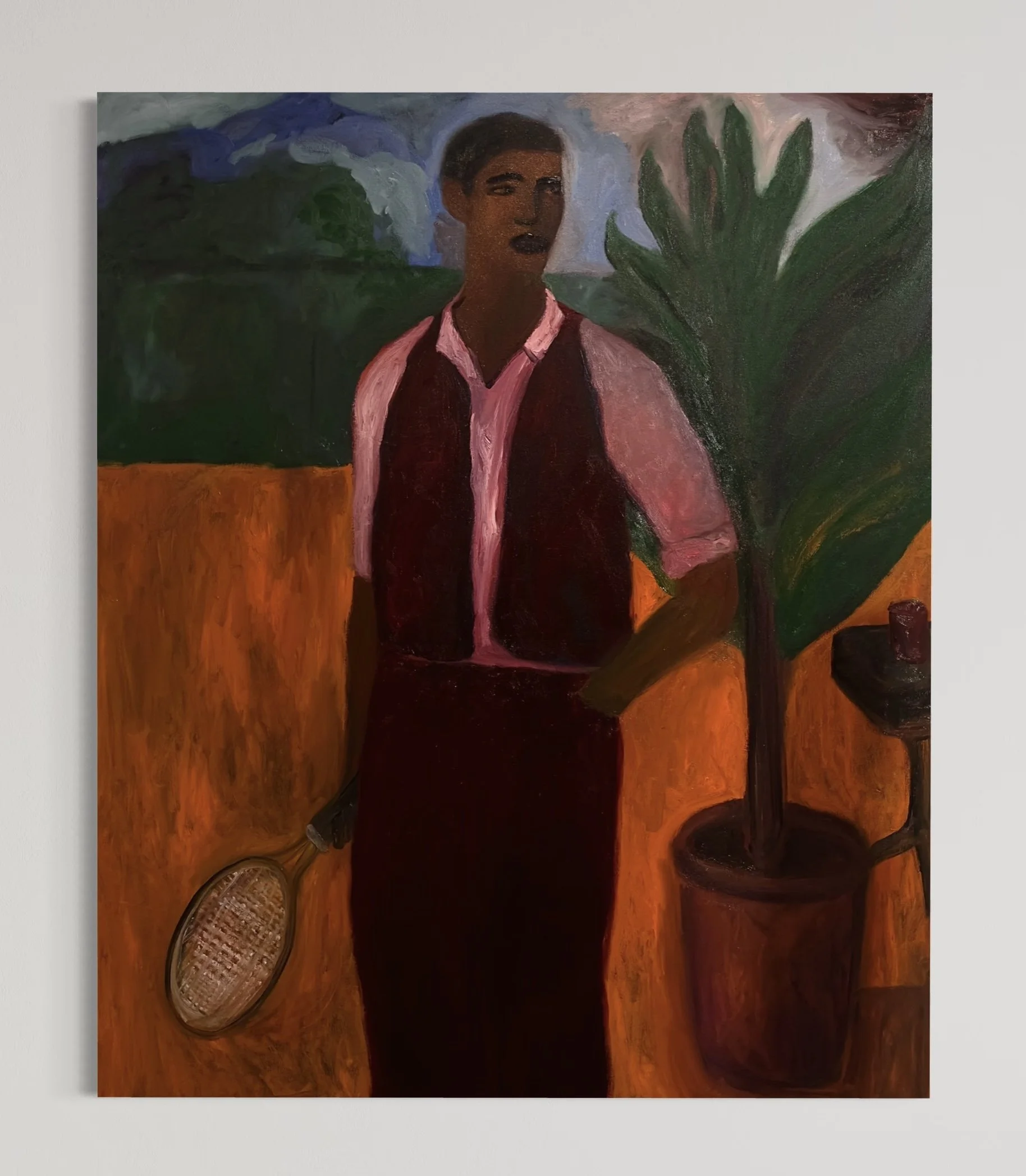

A Lily for the Lost, 2025, oil on canvas, 60 x 72 inches

DG: I recall seeing your exhibition, Solitude, at Mariane Ibrahim. The work was very moving. Tell me about the title and idea behind that series of work.

PE: Solitude was something I'd been thinking about long before COVID, the line between healthy introspection and isolation. My parents and my wife had similar experiences coming from Haiti to New York: excited about the opportunity but feeling locked inside these apartments, missing the community they knew back home. The pandemic just made the whole world live a version of that. The show was my way of exploring that feeling across generations.

DG: There's something timeless about your work, the palette, the posture, the quiet in it. Is that something you think about, or does it come naturally? And who are the artists or thinkers who've shaped the way you see and paint?

PE: I'm definitely an old soul. I love periods where things felt more intentional—music, design, family, community. Life today moves too fast to appreciate authentic craftsmanship.

Photographers like Roy DeCarava and Gordon Parks capture that slower, soulful time, and I chase that feeling in color, in mood. Nostalgia is a big part of what I do.

Madame Céleste, 2025, oil on canvas, 72 x 96 inches

DG: While your work has a reflective quality to it, your presence and personal style are distinctly contemporary. Is that tension something you think about, or do you see those worlds as connected in some way?

PE: It's just who I am, a New Yorker who grew up in the '90s, still got that in me, but I pull from older generations too. I'm not walking around dressed like it's the 1930s, but I borrow from that era. My work does the same thing: it holds onto what was meaningful about the past while living fully in the present.

DG: Your work spans from intimate pieces to larger, more monumental canvases. How do you think about scale when starting a painting or building a series?

PE: Scale depends on where I'm at physically and mentally. In big spaces, I go big, using my whole body. More minor works push me in different ways; it's harder to get the same emotion in that tight space. I like mixing it up to keep things fresh. Lately, I've been building my own frames and incorporating more sculptural elements. That opens up new ways to think about scale and presence.

Man of Arrival, 2025, oil on canvas, 60 x 72 inches

“I’m definitely an old soul. I love periods where things felt more intentional—music, design, family, community. Life today moves too fast to appreciate authentic craftsmanship.”

Paired Sanctuaries, 2025, oil on panel, artist-made walnut frame with burlap, 75 x 50 inches

DG: You recently collaborated with Dior on a series of artist-designed bags. Can you tell me what that experience was like for you, and about the inspiration behind your collection?

PE: Working with Dior felt like taking my painting practice into another medium. There's a heavy history between France and Haiti, so collaborating with a French luxury house was an opportunity to reclaim the "Pearl of the Antilles" in a new way.

I used Haitian materials like raffia and pearls alongside Dior's leathers and gold, abstracting Haiti's landscape and spirit into the design. It wasn't about putting a figure on a bag; it was about telling a story off the canvas.

DG: What was your entry point into the art world? How did you begin forging relationships with galleries or mentors that helped get your work out there?

PE: My first solo show was at a Brooklyn artist-run gallery. Friends from marketing and the art world pitched in, we got press, PBS came by, and NYU brought a class. It was grassroots, just building a community around that space. Over time, those relationships grew, new opportunities came, and I just stayed consistent, pushing myself, knowing there was nothing else I wanted to do.

Patrick Eugène x Dior. Photograph by Heather Sten

Patrick Eugène x Dior. Photograph by Heather Sten

DG: Who are you in conversation with now, whether creatively, personally, or conceptually? Anything or anyone shaping your thinking at the moment?

PE: My family, first, my wife and four boys, give everything I do a deeper purpose now. Beyond that, I'm surrounded by artists I respect and admire through my gallery, and that energy pushes me forward. Lately, that Sweet Flypaper of Life book keeps circling back, making me imagine what kind of collaborations are possible between painting, photography, and poetry.

DG: What's next, whether in the studio, on the road, or in your head?

PE: I want time to create without deadlines hanging over me to travel, take residencies, and really dive in. Long-term, I want to build a foundation in Haiti to support other artists and foster creativity there. In the meantime, I'm focused on pushing my practice further, bigger ideas, new materials, and new ways of telling stories.

C.

Patrick Eugène is a Haitian American painter who creates large-scale figurative works that evoke stillness and reflection. Working from memory and meditation rather than reference, his practice centers on spiritual connection to ancestors and the African diaspora.

Eugène's paintings balance deliberate restraint with gestural freedom—figures emerge from layers of oil on unprimed canvas, elegantly dressed but set in undefined spaces that invite contemplation. A self-taught artist who came to painting at 27 after careers in music production and finance, he approaches his work with the improvisational spirit of jazz, allowing each piece to unfold intuitively.

Patrick Eugène is represented by Mariane Ibrahim Gallery.

Dan Golden is a Los Angeles-based creative director and co-founder of Curator.