On the Edge:

Los Angeles Art 1970s —1990s

from the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Chuck Arnoldi

Lynda Benglis

Billy Al Bengston

Woods Davy

Laddie John Dill

Gregory Wiley Edwards

Ned Evans

Joe Fay

Frank Gehry

Andy Moses

Astrid Preston

Bruce Richards

Allen Ruppersberg

Tom Wudl

Installation photograph courtesy of the Bakersfield Museum of Art

A collaborative feature by Amanda Quinn Olivar and Rachel McCullah Wainwright, Chief Curator of the Bakersfield Museum of Art.

When visitors enter the Bakersfield Museum of Art, they arrive at On the Edge: Los Angeles Art 1970s –1990s from the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection, and are introduced to an in-depth display of over 150 works from some of California’s most notable contemporary artists. This feature offers perspectives from a number of those artists.

On the Edge explores the historical significance and friendships formed between LA artists and the Quinns over those 30 years. In the acclaimed exhibition, Chief Curator Rachel Wainwright addresses the period's experimental approaches to minimalism and new materials, the diversification of practices and makers, and the vital role Joan and Jack played in both documenting and contributing to the story of Los Angeles art.

Each artist was asked the same question. Their responses are shown with an image of work on view and with a new piece chosen by the artist, which communicates their response visually.

How does the period explored in On the Edge continue to inform your current body of work?

Chuck Arnoldi

Chuck Arnoldi in his studio, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist

Joan Quinn used to always dye her hair different colors and at one point she had this blue hair and I thought to myself ‘OK I could make a funny little portrait out of sticks,’ because I was making stick paintings at the time, and I painted the hair part blue.

The funny thing about the other, larger stick piece in the show, I really have no recollection at all about making that piece. Back in the day, Jack Quinn, who was president of the LA County Bar Association, was the most powerful lawyer in town. He just really liked all of us artists, Moses, Ruscha, Larry Bell, etc. Jack would trade us legal services for art; artists would run into a bind, or if we needed any recommendations, or just had any kind of legal question at all we could always just call Jack and he was always available.

Jack had this huge law firm downtown LA with art everywhere, but when I went to see the exhibit I was completely shocked at how much stuff they actually accumulated. Jack and Joan were just great friends and they were there for us whenever we needed.

I’ve found that by making art constantly, one idea leads into another and another, creating infinite possibilities. So in a way, I could say that yes these pieces relate to my current work, but we’re talking about 40-50 years ago. While I kind of change and experiment frequently and I’m not interested in branding myself, it couldn't have led to what I’m doing today without coming from what I did in the past. There’s a thread that runs through everything. I can’t escape myself, even though I try to reinvent myself all the time. There’s a comfort and feeling in a certain kind of a composition or way I approach something.

Chuck Arnoldi, Untitled (portrait of Joan), late 1970s, acrylic on twigs, 12.5 x 14.75 inches. Photo by Ken Marchionno. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Chuck Arnoldi, Untitled, 1970s, wooden sticks, 90 x 70 inches. Photo by Alan Shaffer. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Chuck Arnoldi, Buster, 2021, oil and acrylic on linen, 108 x 90.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist

Lynda Benglis

Lynda Benglis in her New Mexico Studio, 2017. Photo by Matt Hollingsworth. Image courtesy of the artist

I think I went to LA because, as a child, I thought they were talking about Louisiana when they were talking about LA. That’s before I studied geography. When I went to LA and lived in Venice, to me it was just all familiar. They had canals in Venice, like bayous. They had cars. It was this small little town, Venice, California. It was a small little city: all the highways and small little houses, some on stilts, just the ones I’d grown up with near the Gulf of Mexico.

I went to the west coast and made my break with New York. I had been doing those chicken wire pieces and those poured pieces and sparkle knots. I made a few sparkle knots in Los Angeles too. I got into the netting and sparkles when I was in the 2nd grade-3rd grade. I was taking ballet lessons. I had a tutu. I had a sparkle outfit.

I still am doing the sparkle pieces, but am now working with handmade paper. In 2020, I finished a whole series of handmade paper on chicken wire sculptures, some of which were sparkled, and some which had no image at all other than handmade paper and chicken wire. These pieces remind me of the torso figures of my earliest work in cotton, plaster and gold leaf.

Lynda Benglis, Lagniappe I, 1978, cast pigmented paper, acrylic, and sparkles, 36 x 11 x 5 inches. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Lynda Benglis, Madame Butterfly, 2017, cast sparkles on handmade paper over chicken wire, 27 x 26 x 16 inches. Photo by Rich Lee. Courtesy of Pace Gallery, New York

Billy Al Bengston

Billy Al Bengston in Honolulu, 2022. Photo by Wendy Al. Image courtesy of the artist

IT DOESN’T. THAT WAS THEN, THIS IS NOW.

I’M ONLY INTERESTED IN BEING ORIGINAL AND FRESH.

BILLY

Billy Al Bengston, Untitled Dento, 1971, burnished aluminum, 50 x 48 inches. Photo by Alan Shaffer. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Billy Al Bengston, Keaka Koana, 1982, watercolor and collage on arches paper, 46 x 53 inches. Photo by Alan Shaffer. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Billy Al Bengston, Leonardo, 2020, acrylic on canvas, 24 x 22 inches. Photo by Alan Shaffer. Courtesy of the artist

Woods Davy

Woods Davy Studio installation portrait, 2019. Image courtesy of the artist

For me there was a sense of freedom in those days, a raw art innocence, especially in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. Nothing was more important than the work. Nothing else mattered. Through all the difficulties of life, there was a clear and pure passionate vision that did not compromise. Yesterday did not matter, and today was more important than tomorrow, but there was a general feeling that everything would work out.

Joan recognized this intensity in the artists she befriended, and surrounded herself with it. In doing so, she helped many artists by believing in them, making connections for them with other artists, dealers, and collectors. She was and is a true friend.

Today that raw innocence has white hair, but the focus on the work, as it changed through the years, remains constant and intense. The foundation was established in those earlier days. But now that it’s a shorter trip down the hill than coming up it, there is a different perspective. As I get older, for my peace of mind, I feel the need to primarily do one thing really well: one thing which provides me with serenity and stability.

Woods Davy, Dos Ojos II, 1996, stone, 34 x 10 x 8 inches. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Collection

Woods Davy, Cantamar, 2016, stone on granite pad, 41 x 41 x 21 inches. Courtesy of the artist

Laddie John Dill

Laddie John Dill in his studio, 2022. Image courtesy of the artist

My practice with contained light or radiance still remains in the forefront of my experimentation with materials that emit light. Recent experiments have also brought an interest in soft metallic surfaces such as aluminum that trap ambient light, also reflecting interest in use of oxides as pigment in the large curved work at the Bakersfield Museum of Art. The practice of working with these materials is widening for me due to new discoveries of properties of the materials. However, I do not want these pieces to just be a demonstration of chemical interaction. So my main goal is to be able to be efficient enough with the materials to have them realized as I have intended. Experimentation is really the key to my methodology.

Laddie John Dill, Gramercy Park Hotel, 1983, mixed media, 14 x 17 inches. Photo by Alan Shaffer. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Laddie John Dill, JOAN, 2016. hand blown and colored glass tubing, argon gas with mercury transformer, 60 inches. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Laddie John Dill, Red Shield, 2021, welded and polished 6061-T4 aircraft aluminum, convex, 81.5 x 36 x 5 inches. Courtesy of the artist

Gregory Wiley Edwards

Gregory Wiley Edwards by Robert Hale. Image courtesy of the artist

I call the painting technique that's used in the making of my Big Black Paintings series Strokeism. I call the graphic work in the sketchbooks, in some lithographs, in some of the monotypes and in my studio drawings ‘American Hierographyx.’ My current project is a series of abstract paintings entitled Big Black Paintings. In rare instances, Hierographyx are merged with Strokeism, creating personal impressions, meaningful to me, signaling toward the future.

Ever since the late ‘60s, whenever I initiate a drawing, invariably, unknown images will populate the surface of the support and only much later will the meaning and purpose of the drawing manifest in articulate statements. It is as if effort in a certain direction provides the process with qualities that attract meaning from other, different directions, or maybe from an unknown dimension. And so I don't dare try to name a drawing until long after it's been completed. Once meaning exists, purpose can make its grand entrance. A critical mass is achieved and the work tells me to stop, and when to start anew.

In the beginning of Strokeism, I was touched deeply in my first encounter with images of monks in the Buddhist tradition who make one mark on a pristine surface in a box of sand only once every day, then dutifully obliterating the mark and restoring the pristine surface of the sand in preparation for the following day's single mark. I immediately knew intuitively that it held some profoundly magical benefit for my practice. I could use this technique or a variation of it, in an embryonic stage, to expand my field of insight. It seemed to play as the opposite of my drawing.

My understanding is that this activity of making a solitary mark, then erasing it, prepares the mind for acceptance of the dual concept of existence and non-existence. In my painting practice I'm still studying the matter by layering stroke on brushstroke, repeating and canceling, plus erasing then resting before starting again, bobbing, weaving and improvising. My life is not that of a monk in a serene corner of a temple. I make my work in West Oakland. It's complicated. The layering of multiple impressions is a reflection of my reaction to local transmutations, transgressions and transformations, in search of that elusive serendipitous gesture that imbues global meaning onto the preceding marks. In a conversation with the traditional figure to ground relationship, one perfect stroke on top of, or undulating and traversing throughout many previously rendered imperfect ones, captures my predicament and symbolizes the efforts without which I am unable to evolve.

Painting modified my vision of drawing. So in addition to the reading of unknown images as they appear, I'm also more involved with the automatic writing element of improvisation. Taking random steps into the unknown marks my beginning every morning. Following leads left by previous mistakes is my sacred crust of daily bread, my exalted jug of wine. Eventually, every precious tool, castoff object and treasured touchstone is destined to become synthesized with antique symbolism from the river of genius issuing forth and from all the creative tributaries originating in my Spirit, in my African and American lineage, formulating new applications for this art, my philosophy. Drawing freed up by painting. Painting informed by symbolic drawing.

Gregory Wiley Edwards, Untitled (Portrait of Joan), 1993, mixed-media on paper, 26 x 29 inches. Photo by Ken Marchionno. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Gregory Wiley Edwards, Heart & Soul, 2014, acrylic painting on canvas, 48 x 96 inches. Courtesy of the artist

Ned Evans

Ned Evans in his Venice, California studio by Takashi Tomita. Image courtesy of the artist

Ned Evans, Stepping Razor, 1980, acrylic on canvas, 18 x 16 inches. Photo by Alan Shaffer. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Familly Collection

Ned Evans, COCHI, 2020, acrylic and m/media on wood, 40 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist

Joe Fay

Joe Fay in his Livingston, Montana studio by Emily Fay. Image courtesy of the artist

Walking into On the Edge at BMOA I had this powerful sense of déjà vu. Lots of memories stirred my emotions. I associated each piece of art in the exhibit with memories of artists, time, and place, when we lived in Venice, CA. It was great to see my early portraits from 1984 and 1986.

I first met Joan and Jack Quinn when I worked for Laddie Dill and Charles Arnoldi. Later they came to visit my studio. Joan liked my style of drawing and suggested I do her portrait in my style of drawing. Joan Quinn was my very first portrait, followed by Jack Quinn. On the Edge is the first time my portraits have been exhibited in 38 years, since all my portraits were commissioned by private individuals. I’m mostly known for my paintings, sculpture and mixed media works of art, so it was interesting to see these early portraits I did so long ago. For me, it was cool to see the early portraits compared to how much the portraits have evolved. The latest are much more complex and very colorful.

The On the Edge exhibit and artists exhibiting in it still influence my approach to my work. It documents the Los Angeles art scene, and the passion for collecting art, of Joan and Jack Quinn. They were not only collectors, but friends to many artists, and loved visiting and hanging out at artist studios.

Joe Fay, JOAN, 1984, prismacolor on arches paper, 34 x 26 inches. Photo by Ken Marchionno. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Joe Fay, JACK, 1986, prismacolor on arches paper, 34 x 26 inches. Photo by Alan Shaffer. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Joe Fay, Buffalo Bump, 2022, acrylic on canvas, 56 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the artist

Frank Gehry

Frank Gehry ©Alexandra Cabri. Image courtesy of the artist

For me, the lasting power of those works have never disappeared. My impressions of them are still as strong as when they first came out. Mostly, the work seems relevant still, even though the artists have gone onto to do other things, and other artists who riffed off of those early works are still feeding on them.

It’s a continuum.

It was a wonderful time of exploration and freedom, and that for sure continues to influence my work.

Frank Gehry, Easy Edge Chair, circa the 1970s, paper and corrugated cardboard, 37 x 30 x 18 inches. Photo by Alan Shaffer. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Frank Gehry, Pisces Maquette (Portrait of Joan), 2013, paper and wood, 15 x 10 x 21 inches. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Collection

Frank Gehry, Luma Arles building, 2021, 12-level centrepiece on the 27-acre creative campus at the Parc des Ateliers in the city of Arles, Southern France, Courtesy of the artist

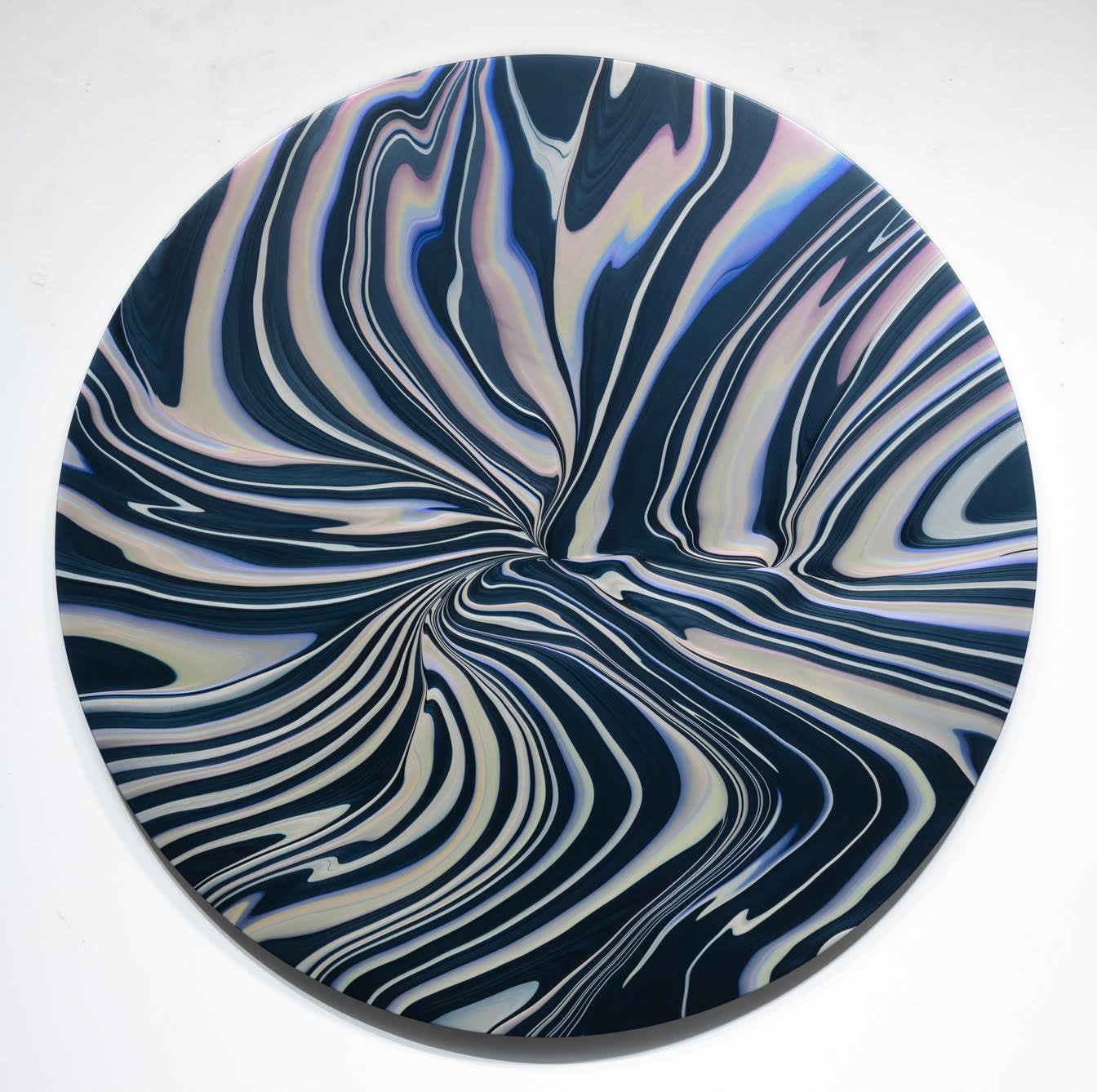

Andy Moses

Andy Moses by Alan Shaffer. Image courtesy of the artist and William Turner Gallery

I can definitely see many connections between my painting Dark Rocks from 1985 that’s in the exhibition On The Edge and my newest painting Geodesy 1226 from 2022. I would say that mystery and exploration are a major part of what I experienced while making both paintings, and also what I want the viewer to experience while viewing them. I want to take a journey and have the viewer come with me.

Both Dark Rocks and Geodesy 1226 through their color palettes suggest nocturnal moments. The night time is when mystery abounds. I have always been interested in images that are simultaneously abstract yet suggest aspects of the natural world. In the 1980s I made a lot of paintings that suggested galactic phenomena. I also made paintings using the same techniques that suggested simple groupings of piles of rocks and stones. I found a way to paint them through a pouring process that involved different kinds of paint reacting with each other.

Almost forty years later I am still working with pouring processes. I’m working in a way that’s both highly controlled yet open enough for me to discover things in the process of making the work. I want to create imagery that feels familiar and that the viewer can connect with but still has a destabilizing effect. I feel like when you are destabilized or off balance you can take in something new. Something fresh. We live our lives being able to recognize everything in our world very quickly and put it in a box. I want to create a world where you feel like you are seeing and experiencing in new ways and have that open up and expand your thinking and sense of possibility. I want to take you on a journey into a parallel magical world.

Andy Moses, Dark Rocks, 1985, acrylic on canvas, 41 x 66 inches. Photo by Alan Shaffer. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Andy Moses, Geodesy 1226, 2022, acrylic on canvas over circular wood panel, 60 inches diameter. Photo by Alan Shaffer. Courtesy of the artist

Astrid Preston

Astrid Preston in her studio by Nobu Takahashi. Image courtesy of the artist

Among many painters in ‘70s and ‘80s Los Angeles there was a movement away from minimalism and toward the use of figuration and imagery in the work. Local artists have always had an eclectic and unique approach to art-making, and been strongly influenced by the light of Southern California.

My painting Freeway, 1984, reflects the revival of image painting and the combining of observation and metaphor. The Romantic notion of Los Angeles as a paradise of light and space continues to influence my current work. The sense of smog, acid sky and sunset in Freeway emphasizes the noir of Los Angeles. The optimism and the dark elements of that period are still felt today. The road, the metaphor of the journey, is more subtle now. Currently my observations and images come from multiple sources.

The romantic history of Los Angeles and also the Northern Romantic Tradition of painting are very prominent in both paintings, although the palette of Autumn Sunrise is brighter. Also there is more attention to detail in my recent work. I have been using geometry recently, with pixilation and/or parallel lines (which appear in the foreground of Autumn Sunrise. I made line drawings in the ‘70s and I reference that in this current painting. Here the lines in the foreground also hint to water rising. My environmental concerns of then and now are present in both works.

Astrid Preston, Freeway, 1984, oil on canvas, 68 x 54 inches. Photo by Alan Shaffer. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Astrid Preston, Autumn Sunrise, 2021, oil on canvas, 24 x 24 inches. Photo by Alan Shaffer. Courtesy of the artist

Bruce Richards

Bruce Richards with his work The Dream of Kings, by Kim Kanatani. Image courtesy of the artist

I met Jack and the law partners in 1980 when they worked on a lease Agreement for the Andrews’ Hardware Artist Studio project DTLA [Downtown Los Angeles].

They allowed us the courtesy to pay our legal fees with art, so my work entered the collection.

The image/object work in the collection resurfaced in 1978 after [I was] working in an MFA program that preferred painting in a minimalist genre…

DeLap, Irwin, Kauffman, Moses, et al… After 8 years being fully engaged in this concern, I returned to the image/object language of my childhood.

As living DTLA within a non-academic community, I found returning to a narrative/personal vehicle could be better sustained, altered and redirected, throughout my life/career as I experienced new and current-day situations.

The lawyers were very supportive of the narrative work, without words, as it was perhaps most like a pictoral legal brief: a concise statement of points of information to be used in a dialogue with title and the didactics presented. The image being the summation of my case.

Ed Ruscha was in the collection and the lawyers (and some critics) sometimes made comparisons. Like Ruscha, I was born in the Mid-West (Ohio), and in 1957 my family moved to California. Prior to the move, I had attended the Dayton Art Institute, and the museum as an environment was my preferred setting. We drew the antiquities in the show cases. Later, in school, I studied mechanical drawing, print shop, arts & crafts, and took commercial art classes. When at UCI [University of California, Irvine] I operated a small commercial art studio and did campus flyers, dance concert posters and graphics… Like Ed Ruscha, I was trained to work in a pre-conceived manner to completion; this was our similarity. The decade that separates Ed Ruscha and myself is the dissimilarity; the main key to our efforts and output are in evidence… His work, for me, then represented the open road of the ‘50s: Movie stars, Big cars, klieg lights, caviar, Hollywood… “Pay Nothing Until April.” My concerns and experiences reflected the turbulence of the ‘60s: Assassinations, Vietnam, Kent State and the Daily News…

And the Music Stops in the On the Edge exhibition concerns competition in art, in life, in community. Who wins when only one is left? If two are viewing the work at the same time, do they notice the other, or just the chair?

Flat World, a recent work, is from the series Course of Empire, and depicts the current global unrest seen in the street fires from the Egyptian Spring, to Paris, to Greece, to Ferguson… the global community condition.

Then, as now, being in such a collection supported the artists’ beliefs and helped to reaffirm our efforts. Collectors nourish the artists’ abilities to continue to expand their purpose. Walking the offices was always a great visual experience, especially to see one’s own work within this context.

A community was presented. It continues in the current On the Edge exhibition.

Bruce Richards, And The Music Stops, 1982-83, oil on linen, 63 x 48 inches. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Bruce Richards, Joan of Art, 1997, oil on lithograph, 11 x 8 inches. Photo by Ken Marchionno. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Bruce Richards, Flat World, 2018-21, oil on linen, 16 x 23.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist

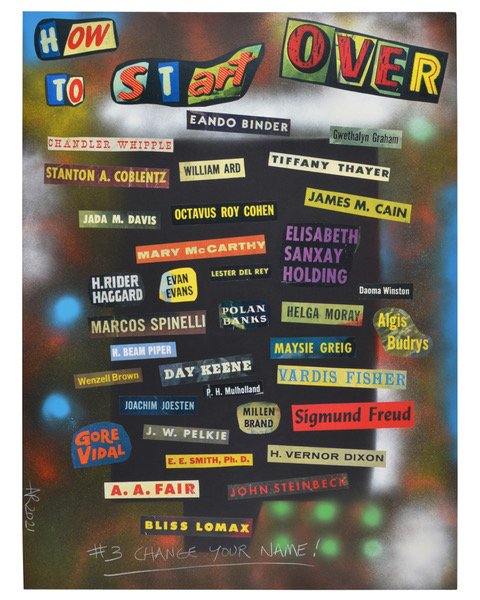

Allen Ruppersberg

Allen Ruppersberg, photograph © 2012 Sidney B. Felsen

One of the concerns that I can see in my works on display in the current exhibition is the love of books and the desire to bring them into the discussion of the visual arts. One of my methods at the time was drawing—and this went on for some years—but I always tried many different approaches to the kind of work I wanted to make. However, to this day, words and pictures, pictures and words remain the main element in most every work, no matter the form I choose to use—photo, drawing, text, video, etc.

It seems all the works come out with these ideas which I now realize have been there since my first serious works in the late ‘60s. Especially in this period I think the idea that reading and drawing have a common denominator—at least in this artist—is something that stands out to me as an important issue I was involved with. But all the works, then and since, have involved a degree of experimentation with different approaches to the categories of art itself.

Looking at the portrait of Joan collected in the show I wonder if I may try that again at some point, as I think all the works I have done in the past can come up again for review. I guess I’m just a recycler at heart.

Allen Ruppersberg, Unauthorized Bio of Billy Al Bengston, 1980, pencil on paper, 30.25 x 24.25 inches. Photo by Alan Shaffer. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Collection

Allen Ruppersberg, Untitled (portrait of Joan), 1983, sculptural mixed media, 48 x 42 x 1.25 inches. Photo by Ken Marchionno. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Collection

Allen Ruppersberg, How To Start Over #3 (change your name), 2021, collage over spray paint, 40 x 60 inches. Courtesy of the artist

Tom Wudl

THE SAME METRIC DEVICES SUCH AS POLYHEDRONS, CIRCLES, ETC, CONTINUE AS THE FORMAL SUPPORT FOR THE MORE RECENT ADDITION OF FLOWERS, JEWELS AND PIPS. MY ARTISTIC MOTIVATION REMAINS EXCLUSIVELY AESTHETIC.

Top: Tom Wudl, Untitled, 1975, mixed media, 19 5/8 x 26 5/8 inches. Bottom: Tom Wudl, Untitled, 1975, mixed media, 21 5/8 x 26 5/8 inches. Photo by Alan Shaffer. Courtesy of the Joan and Jack Quinn Family Collection

Tom Wudl, Tantric Ornament 7, 2021, tracing paper, rice paper, pencil, black and white gesso, 22k gold leaf, 22k gold paint, and gouache, 11.5 x 9 x 1.5 inches. Courtesy of the artist and LA Louver Gallery

BMoA Curator Rachel McCullah Wainwright introduces viewers to On the Edge: Los Angeles Art 1970s – 1990s