October 2025

Notes from Athens

Contemporary Art Spaces

Sascha Behrendt

Photo by Fotini Alexopoulou. Courtesy of the National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens (ΕΜΣΤ).

What does art offer to a society in the midst of both local and global change?

Athens is a city of contradictions, beauty, and grit. Crowned by the serene Parthenon atop its rocky Acropolis, a proud relic of Ancient Greek civilization, it is now a fascinating mix of classical sites, neoclassical architecture, and postwar urban sprawl. Its streets below scattered with cats, graffiti, dusty, cracked pavements, and the thrill of violet jacaranda trees. Occupied by Turkey for 400 years, after independence the capital was rebuilt according to the romantic architectural notions of 19th-century French, German, and English Western powers. It has evolved into a city that culturally still looks back, but through a new generation of practitioners, is reclaiming ownership of its present and future art narratives.

So how does one write about Athens and art, without layering more visions and fantasies onto its culture? The Greek economy is already fueled by tourism, ancient nostalgia, and shipping, and quickly I realised it was unavoidable. Instead, I can only share snatched glimpses via a fragmented, flawed, and foreign gaze.

However, as Western capitalist art hegemony descends into slow-motion stagnation, with shrinking art-fair profit margins and auction-house pricing re-jigged, it was a joy to discover vibrant creativity and intellectual discourse within this socially aware and resistant city. Where diverse models to see, share, and discuss art exist. Here, artist self-presentation is not yet cynical, and away from the markets, possibilities feel fluid yet real.

This is despite the Greek government, which, knocked by the debt crisis after the 2008 Great Depression, has had to prioritize funding to dramatic theaters (up to 400 exist) and museums with archeological artefacts (hello tourism), leaving most contemporary art spaces bereft of public support.

Wealthy private institutions with huge budgets, such as the Onassis Cultural Center (Stegi) and the glittering, futuristic Stavros Niarchos Foundation Cultural Center, have stepped into this gap. With their huge, fabulous, architectural buildings, highly organised teams, and projects such as Onassis’s populist digital art festival Plasmata III in the beautifully restored (by them) fragrant Pedion tou Areos Park, their influence and ‘branding’ can dominate through sheer economic power. Yet with a dearth of artist and curatorial financial support elsewhere, their fellowship programs and exposure have been a lifeline to many.

Nevertheless, scattered throughout Athens are smaller non-profits, founders of which studied critical art theory, philosophy, or curatorial studies abroad, coming home to focus on their own unique local concerns and history. Despite difficulty with funding, and already a wariness against creeping real estate gentrification, the horror of which we see now in Lisbon and Barcelona, many independent spaces host experimental works that, in more expensive cities, are just no longer possible.

Susanne Kriemann, Pechblende (canopy, canopy), library for radioactive afterlife (rhizome cycle) mixed media, installation view TAVROS, 2024. Photo by Stathis Mamalakis. Courtesy TAVROS.

The generous Tavros Art Space, founded and run by the visionary yet pragmatic Maria-Thalia Carras, with her curators Eirini Fountedaki and Manto Psarelli, is above a boxing gym, and named after its working-class area. It serves the local community, but also a loyal, wider arts network, through its exhibitions, film screenings, performances, talks, and workshops. It has recently started to publish books. Many exciting contemporary Greek artists have passed through its doors at one point or another.

Within Athens, the polarization of extreme wealth versus a desperate need for funding has Maria-Thalia conscious of a shrinking Greek middle class, and therefore medium-sized organizations for contemporary art and culture. “It's important to have a cultural democracy,” she says, adding, “What we try to do with every exhibition is think of it as a sort of a bracket for public discourse.”

In these times of instability, whether geopolitical, or economic and closer to home, TAVROS feels like a nourishing and reassuring hub or meeting point for diverse art, conversation and experiences.

Angela Melitopoulos, Matri Linear B - Surfacing Earth, installation view as part of AKIN exhibition at TAVROS, 2023.

Photo Stathis Mamalakis.

Exterior image courtesy of Akwa Ibom.

Another independent space, AKWA IBOM, is an ethically structured and sustained non-profit run by curator and research archivist Maya Tounta, founded in 2019 with Nigerian artist Otobong Nkanga. Tounta is interested in hosting intersecting disciplines, more than just art exhibitions—from fashion by Kostas Murkudis, the designer and ex-assistant to Helmut Lang, to live music events. The spare, beautiful space with old oak floors is set within a neoclassical building in the anarchist area, Exarcheia.

Here, I was lucky to catch Greek artist Danae Io’s exhibition Recording Angel, her film and sculptural works tackling the commodification and slippage of Greek identity, whether through the deceptive musings of 19th century Scottish painter James Skene, or government-issued pay phone cards, nationalistically featuring the Acropolis—yet ironically only needed and used by migrant workers.

Maya Tounta represents two artists-estates Christos Tzivelos and George Tourkovasilis in collaboration with RECORDS. RECORDS is a project founded and run by Melas Martinos and Radio Athènes. Tourkovasilis was a photographer and rare documentarian of 80s rock and punk subcultures in Athens. He recorded life with a passionate, visual, and poetic sensibility, ignoring social norms — all with great aesthetic and philosophical flair. His silver gelatin portrait prints are to die for.

Danae Io, Dial II at Recording Angel, Akwa Ibom, Athens, 2025.

Courtesy of the artist and Akwa Ibom.

Danae Io, Recording Angel (17’30”, 2025), film still.

Courtesy of the artist and Akwa Ibom

Installation view Décalage by Han Ok-hee and Frieda Liappa at Jacqueline, Athens, 2025. Photo by Stathis Mamalakis. Courtesy of Jacqueline.

As the Athen’s art eco-system grapples with its country’s recent politics, economics, migration and history, in response, artist and writer collectives such as The Temporary Academy of Arts (PAT), 3 137, EIGHT / TO OKTΏ, and State of Concept (sadly now only online), have created frameworks for art and politics discussion panels, research projects, and IRL events. The artist and activist Georgia Sagri founded ΥΛΗ[matter]HYLE as an online and physical semi-public site for poets, artists, and researchers. Enterprise Projects is a digital space created by curator Danai Giannoglou and artist Vasilis Papageorgiou that presents writings and discussions via EP Journal, and organises IRL gatherings under the moniker Softwalls. Other alternative spaces include the artist-run Jacqueline gallery, Haus N Athens, Alkinois Project Space, Zoetrope, the new Cypher Gallery, and MISC gallery and publisher. These practitioners, along with others they work with, feel like an electrical undercurrent of arts within the city, responding to both local and wider shifts.

One can’t help but ask, whether some of the unpredictable programming, DIY, and impermanent spaces that exist out of necessity evade the hollowing demands of capitalistic commodification of art, and therefore keep alive, burgeoning original art ideas and expression.

Melas Martinos outdoor detail. Photo by Lorenzo Zandri. Courtesy Melas Martinos gallery, Athens

There are, though, commercial dealers and galleries influencing Athens in positive ways. One of the most beautiful spaces to see art is the architecturally transformed Melas Martinos gallery, transformed by Athens based architectural office Local Local. Hidden amongst the tourist-cluttered streets of Monastiraki, its top floor opens onto panoramic views of the Rond Agora, two mosques, and the Acropolis. Art dealer and curator Andreas Melas shows impeccable sculptural works by American West Coast artists such as Ken Price (who I adore for his weird subversiveness), Ron Nagle, as well as the playful Swiss Nüri Koerfer, whose animals transformed into furniture have the magic of Klara Kristalova’s ceramics without the strange sadness. Melas quietly plays a key role in supporting the growth of visual arts in Athens, and represents, via RECORDS exclusively with Helena Papadopoulos, the estates of interdisciplinary artist Bia Davou, and mathematician, art innovator Pantelis Xagoraris.

Ron Nagle, Rojo Relations, 2024, for exhibition Ode to a Grecian Formula, 2025. Photo by Paris Tavitian. Courtesy Melas Martinos gallery.

Installation view, Ron Nagle: Ode to a Grecian Formula, 2025. Photo by Paris Tavitian. Courtesy Melas Martinos gallery.

Installation view George Tourkovasilis, Radio Athènes and Melas Martinos at Paris Internationale with RECORDS, 2025.

Photo by Pauline Assathiany.

Papadopoulos, a former New York and Berlin resident who is both free in spirit and taste, runs Radio Athènes as an institute for contemporary art. It is not a radio station, but a hybrid exhibition space and a curatorial practice, presenting lectures, screenings, and readings at 5 Petraki Street as its main base. Past exhibitions include Darren Bader, BLESS, Vlahos Vangelis, and Hairy Who’s, Karl Wirsum. Recently, she presented Italian artist Beatrice Bonino’s work within the meticulously renovated TOSITSA3, a historical neo-classical building with beautifully preserved frescos on its ceilings.

Beatrice Bonino, Little low self-inflamed flame, 2025, The opposite of low-hanging fruit, Radio Athènes, 2025. Photo by Yiannis Hadjiaslanis

Also at TOSITSA3, on alternate floors, were two commercial galleries: the Eleftheria Tseliou Gallery exhibiting photography by Greek poet and psychoanalyst Andreas Embiricos; and Hot Wheels Athens, run by Athens and London based dealers Julia Gardner and Hugo Wheeler, who co-operatively showcased as well as their own, works from London galleries, Sadie Coles HQ, a. Squire, Brunette Coleman and Emalin.

Thirteen minutes away on foot, you can discover the small, independent Callirhöe gallery, founded by the German/ Greek, Olympia Tzortzi, who trained as a clinical psychologist before working in New York, Vienna, and Berlin. She runs her business with an idealistic passion for artists and their ideas, which I love, and also represents the formidable and talented Paky Vlassopoulou, who, as well as being a good artist, was one of the founders of the collective 3 137.

Big gallery Breeder is almost an institution by now, with regular participation in international art fairs and instant brand name recognition. Within the Athens art business, they have carved out their own corner, with art and design skewing towards a subversive pop aesthetic. However, its associate director, Nicolas Vamvouklis, who runs his own independent pop-up, K-Gold Temporary Gallery on the island of Lesvos, brings multiple sensibilities to the job, including knowledge of choreography, dance, writing, and curation, and it was he who introduced me to the artist Georgia Sagri and her beautiful interdisciplinary Breeder solo show KORE.

Georgia Sagri, KORE, 2025, installation view at The Breeder Athens. Courtesy the artist and The Breeder

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled, 1981, The Intermission x Galerie Enrico Navarra © Estate of Jean-Michel Basquiat. Licensed by Artestar, New York.

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Untitled, installation view, The Intermission x Galerie Enrico Navarra, 2025 Photo: Paris Tavitian.

For a shift in scene, out on the south coast at the port of Piraeus, and easy to reach by subway, are several art outposts clustered along Polidefkous street. Piraeus is where the ferries and boats depart for some of the 227 inhabited Greek islands, so it has a wild and adventurous feel. It is a relief in the summer, when the city seethes in the hallucinatory heat of 90 °F and up.

One art space there is The Intermission, run by Artemis Baltoyanni, who recently hosted the first exhibition of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s work in Greece. A go-getter based between LA and Athens, Artemis brings a sunny and improvisatory energy, offering her space with its high wood-beamed ceilings as an alternative pop-up for international galleries to show work. I really liked the fact that she hosted NY artist Dena Jago’s paintings. Artemis brings an interesting international curatorial eye and can-do attitude,

A few doors down is the fearless Sylvia Kouvali, running galleries both in London and Athens. In these economically unpredictable times, many have hedged their bets and played it safe, avoiding obscure or conceptually challenging works. Kouvali represents a daring mix; artists include the abstract Austrian painter Ulrike Müller, Leidy Churchman, former Scottish-based visionary Bernat Klein, and Cypriot Christopoulos Panayiotou. A recent show featured conceptual artist/photographer Hari Epaminonda.

Athens hosts many collaborative visual art projects between museums and private institutions. Over the summer of 2025 at the Benaki Museum in Piraeus, the important DESTE Foundation, founded by influential billionaire Dakis Joannou, presented In A Bright Green Field, showcasing 29 Greek and Cypriot artists, curated by Gary Carrion-Murayari, Senior Curator at the New Museum in New York. It is the third group exhibition organised together, and was proudly promoted I saw, in New York.

Onassis AiR Open Day, 2025. © photo Stephie Grape for Onassis Stegi.

As contemporary arts evolve in Athens, many residency programs have emerged, becoming important resources for knowledge exchange. In 2019, the hugely influential and well-funded Onassis Foundation began AiR, a much-needed international arts residency and fellowship program for artists and curators, providing studio spaces and a public platform. It recently launched Onassis Ready, which includes a huge three-floor former factory transformed into workspaces for large sculptures, ceramics, and digital technology. Its Technical Residency program adds specific mentorship and support for work intersecting art and technology.

Onassis AiR Open Day, 2024 © photo Pavlos Fysakis for Onassis Stegi.

Onassis AiR Open Day, 2024 © photo Margarita Nikitaki for Onassis Stegi.

Onassis AiR Fellows, 2025-26 © photo Alexandra Sarantopoulou for Onassis Stegi

Installation view Patricia Trieb exhibition Icon Arms, 2024. Photo by Paris Tavitian. All artwork © Patricia Treib. Courtesy the artist and Arch.

Meanwhile, Atalanti Martinou’s ARCH is a private initiative and spacious art complex, offering residencies, exhibition spaces, a shop with editions, contemporary and vintage ceramics, and a reading art library. Martinou worked young in the high-pressure New York art world with the famed Per Skarskedt, whose impeccable taste with artists and museum-level shows included Cindy Sherman, Cady Noland, Mike Kelley, and Albert Oehlen. Martinou programs her own space in an organic way, listening to artists’ recommendations and responding to opportunities as they occur. This is a luxury she feels is possible in Athens. She says, “If people are focused and really truthful to what they're doing, there's space for everyone to do something that's good quality here.”

Photo of Arch residency interior by Paris Tavitian. All artwork © Patricia Treib. Courtesy the artist.

Portrait of Sozita Goudouna in front of painting Cyclopmedia, 2023, by Mia Enell at Opening gallery New York, 2025. © Mia Enell.

The charismatic and tireless Greek curator and academic, Dr. Sozita Goudouna, was one of the first to offer an official residency program in Athens in 2014, starting with Marina Abramovic and Martin Creed. After moving to New York in 2015 to work on Performa and becoming Director of Raymond Pettibon's studio, she was inspired to found, in 2020, GREECE IN USA, a non-profit supported by the Greek Ministry of Culture dedicated to the exchange of visual arts and culture between Greece and America. She brought to Piraeus, Athens, the inaugural art presentation in 2021 of John Akomfrah’s three-screen video THE AIRPORT (2016) set within the abandoned Ellinikon International Airport in Athens, Greece, as a symbol of both the refugee and Greek financial crisis. Another was Arthur Jafa’s radical Love Is the Message the Message is Death (2016). A work recently shown in pride of place at Pinault’s Bourse de Commerce in Paris.

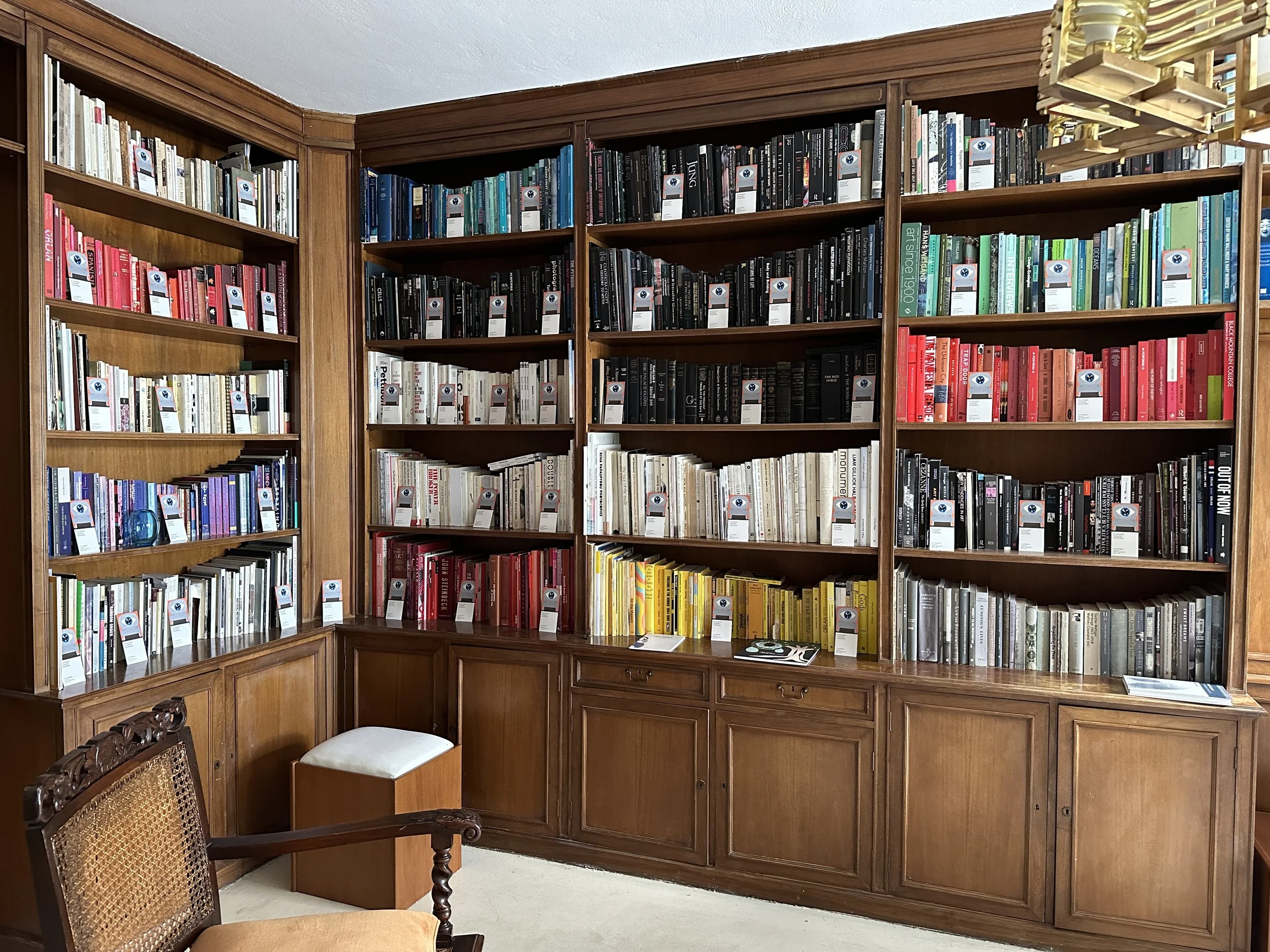

Today, Goudouna curates regular group shows of Greek, Cypriot, and American artists at her Opening Gallery in New York, and in parallel, runs the booklined Library Residency in Athens, Greece, offering the magic of time and space to writers, poets, artists, and performers.

“The idea was to present inspiring Greek artists who were reflecting on issues that were more international or American, and then to exchange with the Library Residency, bringing radical American voices to Athens.”

Recent residents include US writer Hunter Dukes, editor of literary magazine GLOTTA from the island of Hydra, Greek poet Eleni Sikelianos, whose grandparents re-imagined the Delphic Festival in 1927, and Re'al Christian, New York-based writer and editor. The LA-based writer Jamie Brisick, and also director of the documentary, The Life and Death of Westerly Windina, has been working on a novel in progress, In the Malibu Parking Lot, interweaving surfing, identity, art, and philosophy.

Interior of the Residency Library, Athens, Greece

Andres Serrano, installation of exhibition, Torture at Stone Warehouse, Port Authority, Athens. Courtesy of the artist and a/political. Photography by Thomas Daskalakis.

John Akomfrah, The Airport, 2016 © Smoking Dogs Films; Courtesy Smoking Dogs Films, Piraeus Municipal Theatre, and Lisson Gallery. Photography by Thomas Daskalakis.

Courtesy of the National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens (ΕΜΣΤ) Photo by Spiros Rekounos.

On a completely different scale, there is the National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens (ΕΜΣΤ) directed by the experienced curator and art historian Katerina Gregos with her team of curators. Located in the upcoming area of Neos Kosmos, it is the only national institution dedicated to showing Greek and international contemporary art, fully funded by the Greek government.

Aware of the need for creative exchange, it offers six-month residencies for Greek artists via the Künstlerhaus Bethanien program in Berlin, alongside funding eight other international residences.

ΕΜΣΤ was transformed from a former brewery in 1961 and is an impressive example of sleek post-war Greek modernist architecture, finally fully restored in 2020. Today, it holds famed public openings and events on its panoramic rooftop space, and within its vast interior of 194,000 sq ft are sprawling, ambitious group shows, collection displays, and important retrospective surveys.

Nabil Boutros, Celebrities / Ovine Condition, 2014. Courtesy of the artist and ΕΜΣΤ.

Photo by Paris Tavitian

Mark Dion, Men and Game, 1998. Courtesy of the artist, and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York, Los Angeles. Rossella Biscotti, Clara, 2016. Courtesy of the artist.

Photo: Paris Tavitian. All Courtesy ΕΜΣΤ

Gregos presents multi-floor exhibitions that tap into overlooked, yet ongoing, progressive, wider societal concerns. This can range from shows rotating under the concept, WHAT IF WOMEN RULED THE WORLD, to WHY LOOK AT ANIMALS? A Case for the Rights of Non-Human Lives, inspired by John Berger’s seminal essay.

International and Greek artists’ works in the ΕΜΣΤ collections, that may be featured in parallel shows include Chryssa, Theodoros (Papadimitriou), Pantelis Xagaroris, Dora Economou, Jannis Kounellis, Mary Reid Kelley, Cornelia Parker, Ghada Amer, and Paky Vlassopoulou to name a few. One can be immersed, lost for hours, attempting to catch up with ΕΜΣΤ’s volume of visual arts and sculptures — the public space feeling enormous in contrast to the smaller, idiosyncratic Athens spaces elsewhere.

Installation view of the Collection exhibition: WOMEN, together, ΕΜΣΤ Collection. Photo by Paris Tavitian. Courtesy ΕΜΣΤ.

ΕΜΣΤ also runs an International Curators Visiting Program, and prides itself on acknowledging the recent deeply felt need to locate Greek contemporary art and history within a wider geographical context, one that includes the Balkans, Turkey, near Middle East and North Africa. The importance of these regions to Greek art now, and the need to move away from Greek exceptionalism,

was repeated to me by many different curators, historians, and artists that I met. So much so, it felt they were most in touch with the new directions Greek contemporary art must go towards, to honestly connect with its unique socio-political history.

However, at a local level, close to home, within public civic spaces in Athens, there are many hidden modernist art gems. Curator Pati Vardhami describes visiting the city’s town hall on a mundane errand to pick up her resident's parking permit. She was unexpectedly moved to tears at the sight of a beautiful, monumental 33-foot mural by the highly sought-after 20th-century Greek artist Yannis Moralis, alongside ceramic tiles by Eleni Vernadaki within the administration’s routine offices.

It was inspiring to hear, honestly, and without a trace of cynicism, Pati say, “I don’t know if art will save us — but for sure, it will never cease to amaze me.”

Editor Sascha Behrendt is a writer with an in-depth knowledge of arts and culture in the US and UK. Interviews, articles and profiles include artists Amy Sillman, Stan Douglas, Arthur Jafa, as well as features on art and exhibitions in cities around the world.