Margret Eicher

After Botticelli/Birth of Venus (2), 2018, Digital Montage/Jacquard, 94.5 x 165 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

Margret Eicher is a German artist exploring cultural traditions, subcultures, and recurring social and political patterns through large-scale textile works. She is considered a pioneer of contemporary tapestry in Germany, creating works that she refers to as media tapestries. Eicher studied at the Staatliche Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf with professor Fritz Schwegler, and has exhibited her works nationally and internationally at institutions and galleries including the Ludwig Forum in Aachen, Germany, the ARTE Strasbourg in France, the Musee des Beaux-Arts in Tournai, Belgium, the MOKAK in Krakow, Poland, the Museum Liner in Appenzell, Switzerland, and the Haus am Lützowplatz in Berlin, Germany, among others.

Eicher is exhibiting work this December with Michael Jannsen Gallery at NADA Miami and Art Antwerp in Belgium.

Interview by Semra Sevin

How did you become an artist?

As a child, I was always painting and drawing. I was quite talented and received a lot of encouragement and praise from my environment, which inspired me.

Wow, cool.

My family was not happy about it, but I had teachers who supported me. After graduating from high school, I went to the State Academy of Art in Düsseldorf for seven years. At that time, I was only drawing because I was simply good at it. But towards the end of my studies, I found it unbearable to always be defined by this talent rather than by my artistic ideas and identity. I had to find something in which talent no longer played a role, it had become a burden to me... that’s when I discovered photocopies and collages, which I refer to as the CopyCollage technique.

Heart 01, 1997, CopyCollage, 9.8 x 15.7 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

Can you describe the CopyCollage process?

Imagine a photo of a demonstration or a political meeting. I photocopied such images fifty times, for example, then mirrored and line up these copies so that the original image became a mere ornament. In other words, the information conveyed by the original photo is now [in the background and the repetitive pattern of the photocopies becomes the object of focus.

I became interested in this process because it allowed me to create a visually-appealing image by duplicating photographs. To me, the process of duplicating or standardizing is not only a fundamental theme of human coexistence but connected to Siegfried Krakauer’s ideas in his book, Ornament of the Mass, which inspired me at the time. I saw parallels between public images today and the historical courtly tapestry, so I decided to make my own, contemporary tapestries using this process.

Can We Age Gracefully?, 1998, CopyCollage, 71 x 71 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

How and when did you develop your artistic work from collage to extensive work with tapestries?

I have worked with the pictorial form of tapestry for almost 20 years now. In terms of the artistic work process, the tapestries are digital collages. Before that, in the 90s, I made analog collages, with scissors, paper and glue. Even then, I referred to political images in mass media and duplicated them endless times as laser copies in order to then organize ornamental structures of them. These are the so-called CopyCollages.

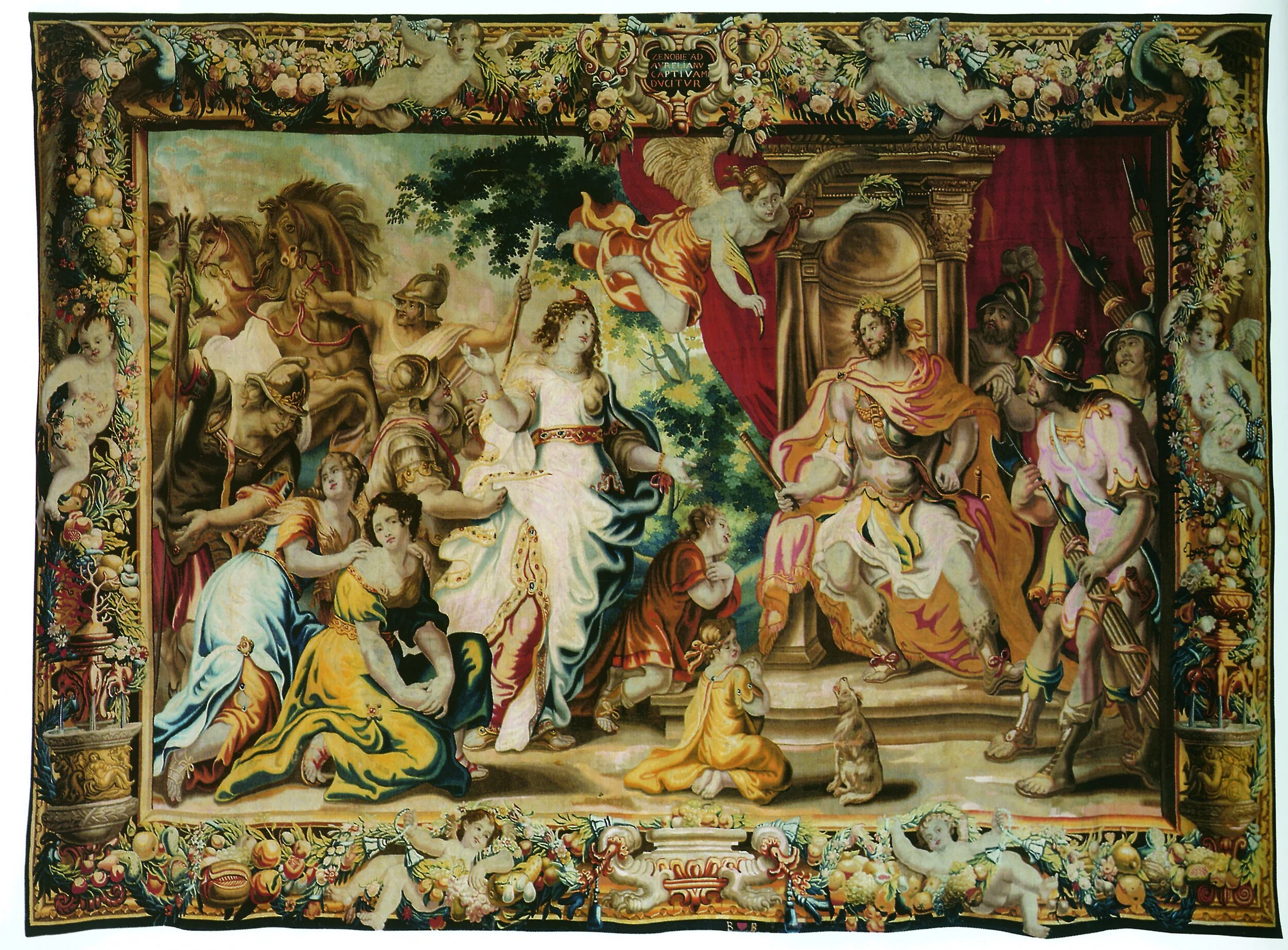

At the end of the 90s, during a vacation trip to the Loire, it was the first time I consciously saw courtly tapestries; these magnificent historical pieces. There, I noticed for the first time that courtly tapestries represented exactly the topics, with which I was already concerned with: Pictures of power, politics, events, world views, idols…These themes are almost always linked to manipulative tactics. That’s what interested me already.

In the 16th and 17th centuries, courts of princes not only staged their valuable tapestries in their interiors, but they also exchanged them among princes in order to present and multiply their world views and to express their immediate opinions. This gave me the idea to design and weave today’s mass media images, photographs, films, and graphics depicting politics, society, gender, etc., in the style of the courtly tapestries. What is interesting is, that historically this genre always includes a central image with additional figures and a commenting bordure.

Amazing Amazon Stars, 1999, CopyCollage, 118 x 108 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

Historical tapestry, 17th century

How has your focus from CopyCollages to tapestry influenced your concepts?

In my CopyCollages, I tried to link all kinds of political and social issues together by creating ornaments of them. Imagine you have a single photo of a politician and you have a single photo of a pin-up. If you put those next to each other, you're suggesting issues that represent banality. If you put the two photos next to each other forty times, separated or mixed, you create an ornament that connects the two in form and content and unfolds a subversive statement.

You work with contemporary media, such as print, internet, film, and popular culture. What is your common thread in an ever-changing zeitgeist?

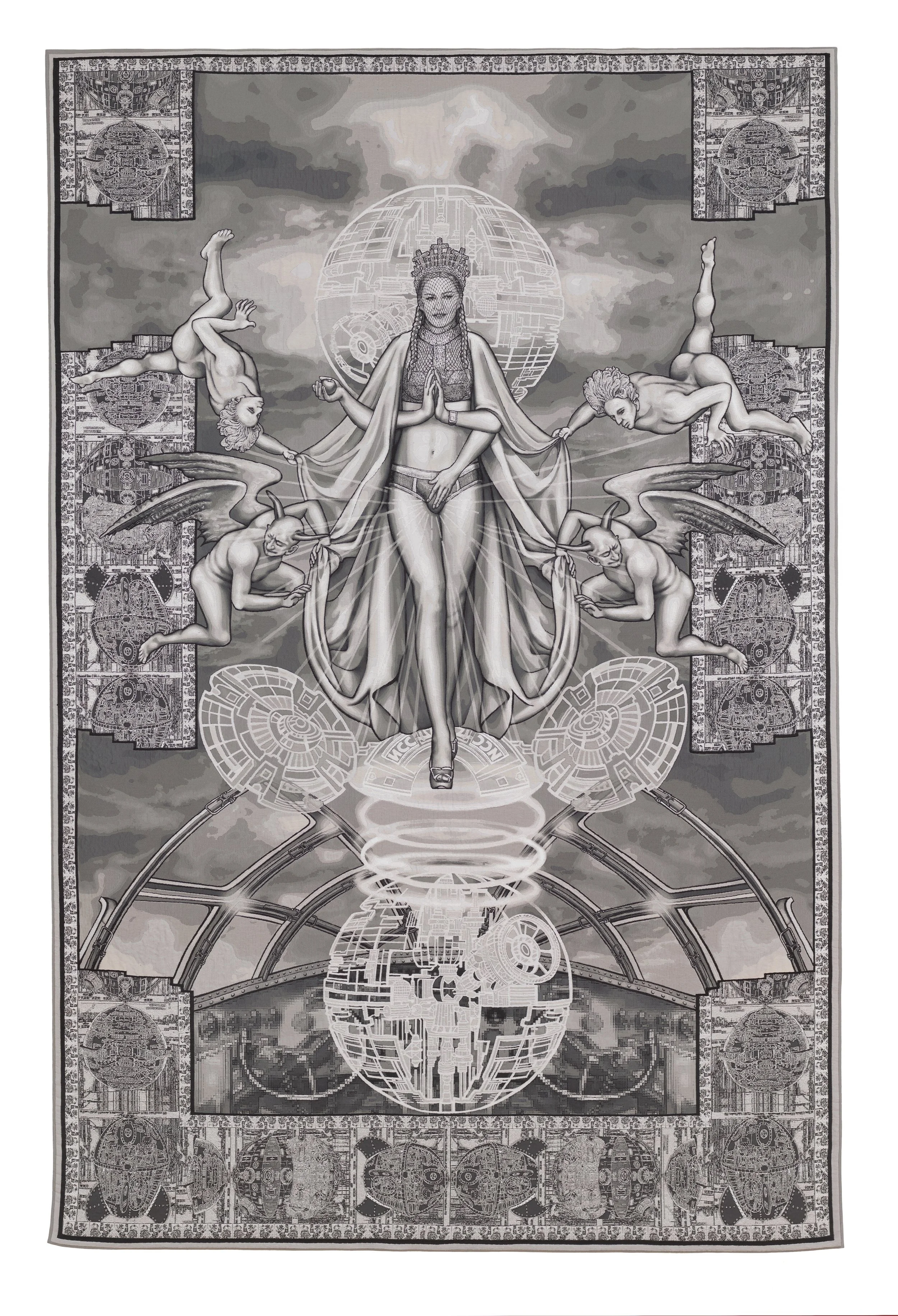

The common threads are the themes themselves which I depict over and over in my tapestries. They can always be found in media, albeit in modification. For example, the image of a social event, the hero or heroine, these are religious motifs. My motifs are rather pseudo-religious! My female figures, for example, often have a religious appeal and their iconographic origin is often in virgin Mary depictions, without being a depiction of Mary. There's the theme of gender roles, which often connects to the hero representation as well. Many of my figures are portrayed like heroes, they are heroized. The whole range of themes of courtly tapestry is still of great importance today, speaking in a figurative way. I look at these themes through the contemporary eye of a contemporary world.

Assunta, 2020, Digital Collage/Jacquard, 121 x 81.5 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

You said that your family was skeptical of your art studies and that your father was an authority figure from whom you rebelled. Is that why your work deals with images of authority and power, deconstructing and reconstructing them?

Yes, I grew up in a conservative environment in which there were strict rules that I opposed in accordance with the zeitgeist of the 70s. You could say that to this day I have a high level of vigilance against anything that appears authoritarian, and I find it hard to bear it when power structures impose guidelines on me. My artistic view of social power structures or the implementation of power and manipulation may be rooted in such early experiences.

What does the hero mean to you and why the preoccupation with the hero?

Heroization is an almost common gesture of figure representation in classical art. Connected is the concept of pathos; a theme or a figure or an action is not depicted in a banalistic-realistic way, but in an exaggerated, sublime and idealized way. I find sublimity very interesting, especially with regard to the female characters. For example the banal representation from a quickly shot journalistic photo. With the help of small compositional shifts one can create a new different value and interpretation. Creating a completely different view of a figure through a creative process is a recurring work process in my art.

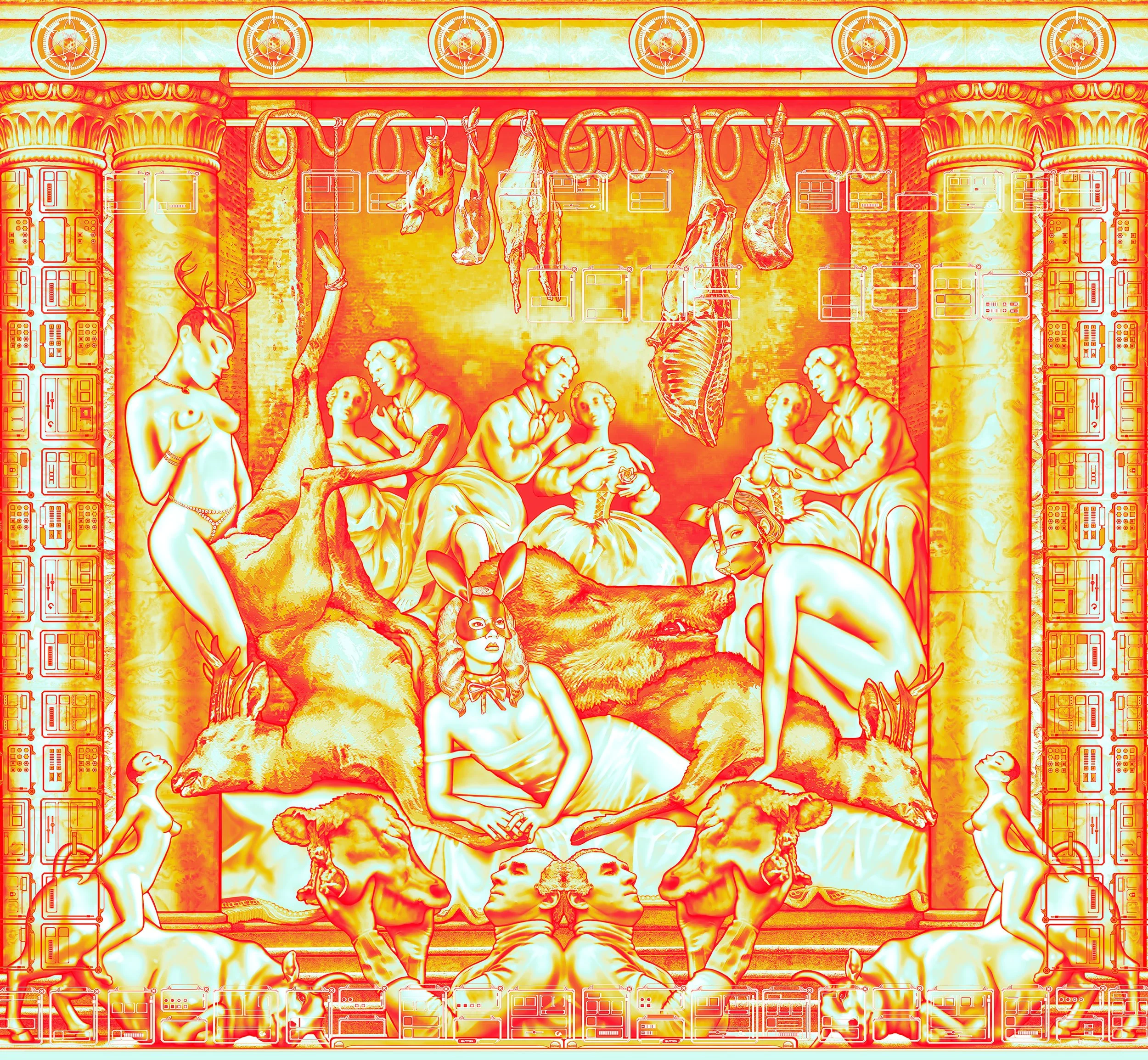

Heroes 2, 2012, Digital Montage/Jacquard, 116 x 130 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

Big Piece of the Lawn, 2013, Digital Montage/Jacquard, 108 x 167 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

Are there hero figures you watch critically?

That varies. A positive example is Beyoncé who is interpreted as Venus in my work After Botticelli. Venus is an ancient mythical heroine, an archetype of the feminine. Beyoncé, for her part, is to be a celebrity with a very positive connotation, since she expresses herself in an emancipatory and feminist way and has an impact on social discourses. Here, the contemporary phenomenon and the ancient myth merge into one. I find it also interesting that she is an idol of the present; this makes her important to me. Whether I am personally connected to her is not the question, but that she is of importance to many in the time in which I live - that fact is crucial to me.

You cite the tapestry because of its iconography and the representation of power. Do you perhaps refer to the contemporary world through a historical medium that exerts power over world views?

Yes, today's pop icons are culturally synonymous with the ancient goddess. The god of war also appears at the conference table of the DAX company. Tapestry has always been concerned with these themes. It has been used to define the world, to convey a world view, and thus to exercise power.

The Judgement of Paris 3, 2012, Digital Montage/Jacquard, 118 x 201 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

City of Women, 2016, Digital Montage/Jacquard, 104 x 142 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

How is it that you can so eloquently describe your concepts, work and the history that goes with it?

In addition to my artistic activities, I taught art history for many years and thus simply learned to express myself clearly during lectures and in conveying art. That was my aim, that people could actually understand my analyses. Sometimes you read texts about art that you can only understand with a lot of goodwill. My aim is that even someone who doesn't want to know can understand me. Teaching art has taught me a lot about thinking and speaking about art. If you can talk about Dürer and people can understand you, you can also talk about your own work.

You studied in Düsseldorf. Were you born in Düsseldorf and how did your artistic career develop?

I grew up very rural, in the Lower Rhine near Düsseldorf and I studied in Düsseldorf. After that, I moved to southern Germany, because I quite classically followed my big love. Our relationship, unfortunately, ended in my mid-30s after which I lived for many years near Mannheim and Heidelberg. I felt comfortable in the province because at the same time I was mobile and showed my work everywhere. It was only ten years ago, that I moved to Berlin. At first, I commuted between Baden and Berlin and for three years I've been here in Berlin full-time.

Berlin has been interesting to me for a long time, but I hesitated because Berlin is just so incredibly far east of Europe and Germany, so continental. I find it attractive when you can be in Paris in four hours or on the Atlantic coast in five. I've always been drawn to the west and the south. Berlin is good for my work though, I benefit from this city and I meet great people here, like you for example. But being in the middle of the continent now, I find it somehow strange. Maybe it's an escape reflex. My mind is constantly thinking: where is the nearest port?

Divine Love, 2011, Digitale Montage/Jacquard, 102 x 114 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

How has your visual language changed, since you moved to Berlin?

In my pictorial language, something major changed five years ago: I moved from colored representation to black and white and gray values; color was eliminated from my works. This was due to the fact that all the colored works - as you can see - show very pleasant tones and warm colors. I was not quoting the historical tapestry as it looked in its time, but as we see it today; that is, faded and discolored either into the blue or the reddish. I looked at how these fabrics have aged and which colors remained stable and which faded. By mimicking a faded, historical piece, I wanted the viewer to believe for a second that they were looking at a historical original, but of course, immmediately realized the error.

It seemed to me then, a few years ago, conceptually inappropriate for the works to be so beautiful, soft, warm, and pleasant. After my move to Berlin, I felt this trivialized my subjects and I wanted the effect to be harsher and more rational in order to make it more uncomfortable for the viewer. At first, I thought if the color pallet would be more stark and garish I could create that effect. Then I experimented but it always turned out to look like a comic and that couldn't be it. After that, I renounced color and that look convinced me because retreating into black and white meant that I distanced myself from the historical model and also the contemporary image model, which also is very colorful. Thus, I pioneered my very own creative space and became more independent of my original two sources of quotation: historical tapestry and modern media.

It’s a Digital World 1, 2014, Digital Montage/Jacquard, 118 x 59 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

Your work process is meticulous and you can only really develop a certain amount of works each year. How long did it take to weave After Botticelli, the Beyoncé tapestry?

Yes, I usually have three or four different works in progress on the computer at the same time. If I don't get anywhere with one motif, then I move on and three days later it works again. The motifs I work on at the same time influence each other like siblings. The piece After Boticelli took at least half a year. This motif has gone through endless changes. It happens that a motif is almost finished only to change after I come up with another supposedly better idea. Then, I rebuild the whole thing again. That was also the case with After Boticelli, especially in regard to the background space, which is a Frankfurt subway station.

The borders of your works have also changed over time. I have the impression, some are a bit more baroque and others are more classical. Does that have any significance?

In the first few years, I always used historical borders, then I moved on to do to mixing historical and contemporary originals. In my work Divine Love, the columns framing the sides are historical, but above and below, as you can clearly see, I use new pictorial material. In After Botticelli, you can see sections of a historical tapestry at the sides. But then again, computer writing around the outside borders. In the lower border area is a Japanese tattoo motif: wave and cherry blossom. Because in mythology and also in Botticelli's picture, Venus stands on a sea spray.

It’s a Digital World 2, 2018, Digital Montage/Jacquard, 122 x 71 inches. Photography by Nicolaus Steglich

How did you come up with the work, Agent Assange?

I have been following his fate in the news and was very impressed that he created a significant enlightening platform with Wikileaks, to expose and publish political crimes, human rights violations, and atrocities committed by governments and global corporations. It is still inexplicable to me that no European government stood by him.

Agent Assange (exhibition view), Digital Montage/Jacquard. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

And the Ninja Turtles ... I think they are especially cool!

These are also secret agents; these characters are derived from the ninja in ancient Japan. Here they depict allies or protectors.

Does your work relate to your family history?

Indirectly, yes...The ancestors of my father were weavers. These ancestors moved like many others in the middle of the 19th century from Belgium to the Lower Rhine because they where so poor. In the Lower Rhine area the weaving industry was developed and labor was in demand.

Detail of tapestry. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

First Night, 2008, Digital Montage/Jacquard, 106 x 144.5 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

I would like to talk about the 90s. You also witnessed that decade in the German art world. What effect did the fall of the Wall have? First of all, tell us what it was like before, and did you live in the Rhineland when the art world was booming in the 90s?

I no longer lived in the Rhineland but was there very often. You had to be there; openings, exhibitions, and visits. The Cologne Art Fair and the Cologne Gallery scene set the tone. You could see international art. In my opinion, there was such a concentration and pulse of a vibrant art scene, like nowhere else in Germany later. The reunification also changed the view on art gen-res. Painting became important, after years of focussing on conceptual art. Then there was the discovery of photography as an art form in Germany. The artists from the former GDR, but also from the Eastern block in general, pushed these themes. They had different art traditions. Painting played a big role in the GDR, photography in the Czech Republic or Hungary. There was an unbelievable cultural potential unfolding from the previously hidden countries and of course, new market potential.

And the novelty effect opened the art market for these genres, so to speak?

That was at least the general sentiment. Young Western German artists felt that way. There were some Eastern German artists who made rapid careers. In the former GDR, the academic training was very good. Previously oppressed by the state, a new scene developed explosively, and that was of course exciting and great. But you also noticed that West Germany was no longer the best place to be when you contacted institutions. It was much more conducive if you were from Leipzig or Chemnitz.

Praise to the Art of Painting, exhibition view at Museum Villa Stuck, Munich, 2020. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

Praise to the Art of Painting 2, 2018, Digital Montage/Jacquard, 114 x 169 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

Can you tell a little bit more about how it was before the wall came down?

In the 80s, the art scene was not yet as internationalized as it is today. When artists exhibited in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. And if they found resonance and had networks in the German-speaking countries, that was already considered as being very successful. And German artists who were also seen in America or England were world stars at the time. The global orientation, including the Far East, came later. Larger German galleries gradually started opening their branches in Southeast Asia, in Japan or China, Singapore, or Russia.

This started at the end of the 90s, but especially in the 2000s. The claim to internationalization has remained. Global thinking in the economy and the financial world, in the service and industrial processes, has become just as naturalized in the art market and it has also been solidified as a value. Not to forget, the fall of the Berlin Wall was also accompanied by many budget cuts in state support for the arts. It has become much harder to get shows, projects, and catalogs funded by the state, than before. There is less money from the government than before. The focus has shifted.

After the Hunt, 2008, Digital Montage/Jacquard, 118 × 193 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

What do you think of the new market with NFTs?

On the one hand, I'm attached to the analog, the tactile material, and the sensuality of things. Last but not least, I turn a digital artistic work into an analog, very tactile tapestry. But I still find this idea of the crypto art market very interesting. And that's because the digitalization of life can no longer be put into perspective. We are on a path that will probably shape the future in a much more serious way than we think. Economic and ecological development will continue to drive digitization forward. But we will probably still face many things that will make 'real life' difficult and that’s where digitization will offer an alternative, see the Corona pandemic. In this respect, I am very interested in the digital art market and together with my gallery Michael Janssen, I am exploring this medium.

The Grand Feast, 2019, Digital Montage/Jacquard, 98 x 106 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

The Grand Feast, 2021, NFT, 98 x 106 inches. Photograph by Nicolaus Steglich

Some artists stick with one visual language for decades. As you deal with contemporary media and pop culture, you are constantly faced with the actual state of the world. Does this have an influence on the dynamics of your visual language?

After all, I want to entertain myself when I'm working. The entertainment factor has something to do with risk. For example, the risk that a work could be perceived as tasteless, kitschy, incorrect. I have the urge to try something that I don't know how it will turn out. There are certainly many artists who once they have found a form, then enforce it a very, very long time and very uniformly. Perhaps like a recipe for success. When I think, for example, of painters like Lüpertz or Baselitz, both very famous and successful - they've been doing the same thing for at least forty years. This continuity is primarily for reasons of material success. Of course, someone only buys a Baselitz, for example, if they recognize it as a Baselitz.

Can you tell me what's next for you?

First of all, the group show, SCHÖNESHOW, to which you invited me in a community garden in the middle of Berlin. Then, in August, an exhibition I curated two years ago for the Foundation of Prussian Palaces and Gardens, which was shown in Caputh Palace in Potsdam, will be shown in Pillnitz Palace in Dresden with the same cast which four artists and me. Next year, I'm working on a paraphrase of the Bayeux Tapestry, a famous medieval tapestry. That tapestry is over 60 meters long and it shows the Battle of Hastings, how William the Conqueror moved to England. My work will only be 30 meters long and will show largely a digital battle action and virtual battle fantasies of the present. My work will be shown next year at the Museum Moritzburg in Halle, Germany.

This year, I am excited to be represented by Michael Janssen Gallery from Berlin at the NADA Art Fair in Miami Beach, as well as at Art Antwerp in Belgium.

Portrait of Margret Eicher, exhibition view at Galerie Michael Jannssen, Berlin, 2021. Photograph by Estefanía Landesmann

All images courtesy of Margret Eicher