December 2023

Lisa Congdon

Dan Golden speaks with the talented artist, designer, and illustrator about her creative process, inspirations, and new solo museum exhibition. life,

Sajan Vazhakaparambil Kolavan Kalyanikutty Mani (1981) is an intersectional artist and curator hailing from a family of rubber tappers in a remote village in northern Keralam, South India. His work voices the issues of marginalized and oppressed peoples of India via the “Black Dalit body” of the artist. Mani’s performance practice insists upon embodied presence, confronting pain, shame, fear, and power. His personal tryst with his body as a meeting point of history and present opens onto “body” as socio-political metaphor.

Several of Mani’s performances employ the element of water to address ecological issues related to the backwaters of Kerala and the common theme of migration. His recent works consider the correspondence between animals and humans and the politics of space from the perspective of indigenous cosmology. Unlearning Lessons from my Father (2018), made with the support of the Asia Art Archive, excavates the artist’s biography in relation to colonial history, botany, and material relations.

Sajan was the first Indian to be awarded the Berlin Art Prize in 2021. He has participated in international biennales, festivals, exhibitions, and residencies, including The INHABIT, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, DE (2022), Galerie Leonard & Bina Ellen Art Gallery, Concordia University, CA (2021—2022) Lokame Tharavadu Kochi Biennale Foundation, IN (2021), Times Art Center Berlin, DE (2021) Nome Gallery, Berlin (2021) CODA Oslo International Dance Festival, No (2019), Ord & Bild, SE (2019), India Art Fair (2019), Specters of Communism, Haus der Kunst, Munich (2017), Dhaka Art Summit, Bangladesh (2016), Kampala Art Biennale, Uganda (2016), Kolkata International Performance Arts Festival (2014–2016), and Vancouver Biennale, CA (2014). In 2022, he was awarded the Prince Claus Mentorship Award and Breakthrough Artist of The Year from the Hello India Art Awards. Between 2019 and 2022, he received an artistic research grant from the Berlin Senate, a Fine Arts Scholarship from Braunschweig Projects, and the Akademie Schloss Solitude

Mani is represented by NOME Gallery (Berlin) and Shrine Empire (New Delhi).

What were your first memories of art? Was there a moment of epiphany where you thought you had found your calling?

As a child in school, I was interested in what was beyond academia—what we call “extracurricular.” Drawing came naturally to me; I experimented with different mediums. Where I grew up, there was no formal mention of an MFA degree or art education. Artists had difficulty gaining social acceptance because of the taboo that followed the profession. My parents were rubber tappers, and many of my memories revolve around the rubber crop: the smell, touch, and sounds of the plantations. All tend to seep into my work.

I choose not to differentiate between my personal biography and artistic practice. It is always intersectional. Also, to think of it now, being in my body was, and continues to be, a performance. For instance, I can’t begin to count the number of times I was called aside at airports and railway stations for checks. Once, I nearly got arrested at a train station! See, there is a friction of sorts. So, theoretically, you always had to prepare yourself for performance. It continues to be an integral part of the routine.

What have been some important references throughout your practice? Are there narratives or scapes you keep moving back to?

I grew up surrounded by books that were printed in Moscow, brought to Kerala, and scribed in the language of Malayalam. These volumes were not only about Marxism but also about science, among many other subjects. The Communist Party came to India nearly a hundred years ago and maintained a strong presence in Bengal and Kerala. The party played a significant role in social reforms in Kerala in particular. Over time, Kerala’s socio-political landscape has become more egalitarian because of communist movements and Narayana Guru’s philosophical engagement with the question of caste, Ayyankali’s interruptions to the casteist public spaces, Poykayil Appachan’s revolutionary socio-political, spiritual movements such as Thycaud Ayya. This is particularly evident today in the wake of ongoing right-wing Hindutva activity in the northern part of the country. I grew up seeing monuments dedicated to Communist Party workers who Hindu right-wing forces had killed. These monuments of resistance became a part of my visual memory and inform my artworks today.

In my artistic practice, I write and draw—in the sense of drawing as writing, writing as drawing. I look back at the narratives of Dalit and indigenous people to recast their pain, shame, fear, and power. There is a back and forth in which I revisit myths and rituals. For example, my performance titled Caste-pital references a ritual dance form called Theyyam. Theyyam carries with it a history of resistance. During the ritual, lower-caste people embody gods. Participants predominantly use colors such as red and black. Some Theyyam songs, like Pottan Theyyam, contain explicitly anti-caste and revolutionary elements. But they also have a spiritual dimension. This brings me to frameworks discussed in historian P. Sanal Mohan’s 2015 book, Modernity of Slavery, and histories of Dalit social reformers such as Poykayil Appachan, which also influence my practice.

The idea is to think beyond dominant historiography and foreground a Dalit and Indigenous cosmology. Hindu scriptures and mythology (such as the Vedas) or ancient Sanskrit texts in the framework of Brahmanical Knowledge production perpetuate a discourse that insists on depicting lower-caste people in bad light. I aim for a disconnect beyond the canon, perceiving my body as a meeting point for history and the present.

Sajan Mani, Caste-pital, 2017, performance, Haus der Kunst, Germany

Please tell us about your artistic project, Political Yoga. What led to the project’s inception, what does it stand for, and is there an end goal you expect from the ongoing project?

As I got to Berlin, I couldn’t help but acknowledge the presence of yoga. Everywhere I went, there seemed to be different iterations of yoga, all being run by Europeans and Americans. There was Beer Yoga, Goat Yoga, all kinds of them! I saw it as a way for the West to connect themselves to the East, having their own Yoga Day celebrations and merchandise that followed. One must recognize the capitalistic endeavors associated with ancient knowledge, such as yoga. In contemporaneity, its affiliations go beyond a yogic way of being. It is now more like a business, with millions of dollars pumped systematically to fuel an entire industry.

The Indian Hindu right-wing minister came to Berlin to celebrate International Yoga Day, which falls on the 21st of June. This was in the capital of Germany, where a huge crowd gathered in Alexander Platz, the kind of center of Berlin. When I saw this, in a way, I found it hilarious but, on the other was also alarming, considering where this incident was situated. We had the Alexander Platz, the history of Eastern Germany and West Germany, the wall, the Nazis, violence that followed—all these thoughts rushed through me to question the relevance of yoga happening at Alexander Platz. I then took to research to understand the history of yoga.

I found this one interesting study by Mark Singleton, published by Oxford. According to this study and many others, modern yoga has nothing to do with India. Modern post-postural yoga is actually an American product that has more to do with marketing a certain lifestyle or organization. But, you also then ask yourself how a country like India successfully uses yoga as a soft power technique. Yoga is being celebrated in the United Nations and across the globe without setting inquiry on the political agenda.

Political Yoga is a project that stemmed from these occurrences, and my interest as an artist was in critical research of my findings or observations. Political Yoga is a sonic performance with a posture you follow, similar to a Shavasana. As part, I invite you to come along with me on this journey that is not only artistic but also meditative. Following my voice, there are procedures conducted; all conveyed via a set of instructions. It is an experience that takes you to a different stage and a collaborative project where not just an audience but also professionals come on board to make it an exciting journey for all.

Sajan Mani, Political Yoga, 2023, Kampnagel, Germany, © Robert Maybach

Sajan Mani, Political Yoga, 2023, Kampnagel, Germany, © Robert Maybach

“I aim for a disconnect beyond the canon, perceiving my body as a meeting point for history and the present.”

What was the core propeller behind the presentation, Wake up Call for My Ancestors?

My practice must create counter-narratives to hegemonic, dominant knowledge systems that have erased or misinterpreted particular histories. For instance, Dalits are seen as demons in Hindu mythology. I see it as a duty to source, assess, archive, share, and produce material to allow this plurality to exist. You have to look into the land, you have to look into the body, you have to look into the oral traditions like folklore or songs. Another method is looking into colonial archives and closely understanding the work’s authorship. The way of post-colonial looking into colonial archives is mainly controlled by the Indian upper caste all over the academia, and that, too, leaves an imprint of a certain bias.

Literary figures such as Gayatri Spivak, to the extent you consider, speak of important beliefs such as the loss of Kohinoor. But, little is there knowledge about the kind of subjugation that was inflicted on minorities by the same kings who were once the holders of the diamond. There was an internal colonizer before the external colonizer. Knowing indigenous and Dalit perspectives or histories of the working class is equally crucial.

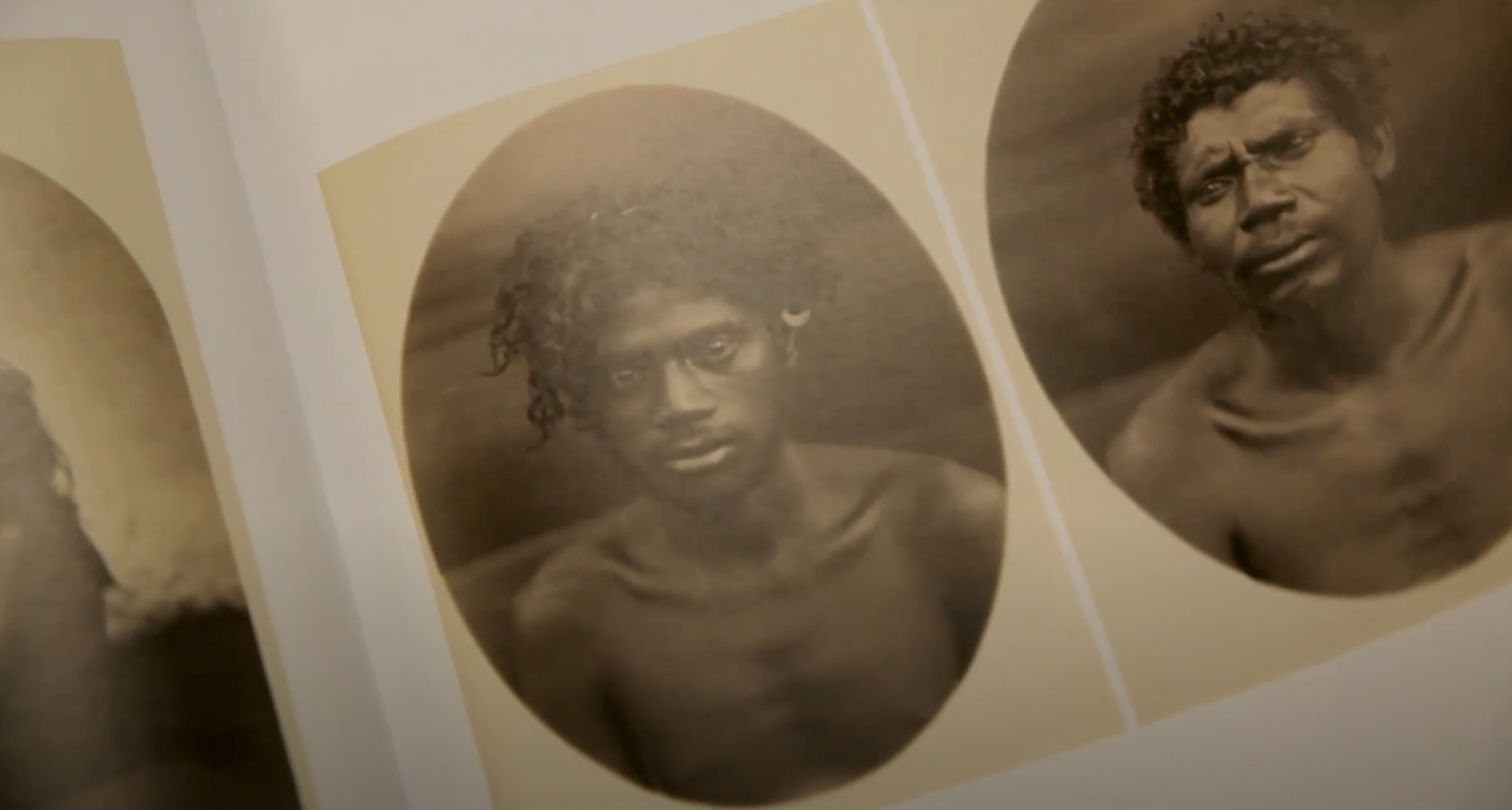

My interest in these lesser-known histories led me to look into various archives in Germany. My mother tongue has a very complicated history with Germany; that was another motivation. Hermann Gundert was a linguist who compiled the first dictionary for Malayalam. Using that manuscript, I imprinted the found text as a serigraph on rubber sheets as a kind of archival research. I also saw a catalog titled Colonial Eyes from the Ethnological Museum of Berlin. The cover caught my eye, so I bought a copy to look at what was part of the publication. To my surprise, there was a rare photograph of women from the Tandu Pulayas community. Pulaya is one of the lower castes in Kerala. The image was from Travancore, 1890, published by The Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (Berlin State Museums). Three pulaya grandmothers stood in the middle of hay in front of their working place, in garments that left their breasts bare. These archives were incredibly hard to access because of how rare they are. I shared this image with friends and colleagues as a means to document. This instance also led to a push towards more research and was the drive for Wake Up Call for My Ancestors. This conversation, or reflection on museum collections, is a drastic shift from the ongoing discussions and understanding of what India is, mainly through European viewership, that reduces Indian cultural material to either characteristics of Buddhist, Mughal, or Hindu Vedic imagery.

Sajan Mani, Wake up Call for My Ancestors, video, 2022

Over time, do you find there are significant shifts an artistic trajectory undergoes while navigating different contexts (be that institutional or geographical)?

Of course. Given that I am currently in Europe, if I look at the institutional presentation, the main challenge is to be an educator initially. The identities and ideologies that form the essence of my practice need to be conveyed first before my work is recognized—certain existing privileges within the fabric lead to subconscious ignorance. Therefore, they need to be spelled out gradually before they come to light—for example, the definitions of concepts of caste versus race. In India, this challenge transforms and shows itself in a different form. As Gajendran Ayyadurai argues, we need a critical caste consciousness now. If people in the West can’t understand what we mean by Brahmanical Knowledge Production and how caste is a global phenomenon, please read Vivek Ramaswamy’s Biography.

I have realized that some works are celebrated more in certain places, considering the context, underlying histories, and capacities to empathize. However, this does not drastically change the course of my practice. I am not interested in image-making just for the sake of. Through my imagination, I must challenge the very idea, the very notion, of an image. This is my politics and a chosen way of conducting practice. I look at it as a historical responsibility.

Sajan Mani, Malayalam As The Body, serigraphs on natural rubber

Are there any recent or upcoming projects you would like to highlight?

I have an upcoming publication as a subsidiary of Wake Up Call for My Ancestors. The book is looking towards the contribution of curators, artists, and other art professionals. I am glad to say this has been organized without institutional support, which means the journey is not limited. I am still looking into archives to facilitate more than what is already in place. Its second iteration, Speaking to Ancestors, is also curated by Pauline Doutreluingne and Keumhwa Kim. It is going to be a larger exhibition. One can expect installations, video works, and sculptural elements as part of the show, taking place in Berlin.

At the moment, I am spending more time in the studio, experimenting with natural raw rubber sheets to produce large-scale tactile and smelling installations and also producing more drawings and paintings, thinking a lot about ecology and trying to sway between studio time, research time, and private life.

I will have a solo show at Galerie Melike Bilir, Hamburg, in November 2023. There are also two performances coming up early next month. This will be In Finland, part of the New Performance Turku Biennale. I was studying a river in Kerala. It was an important site growing up. The performance is a mapping of this river through the medium of my body. I performed and documented the performance to create this new piece of video work. It is a learning from the late Kallen Pokkudan, an indigenous leader, who planted mangroves on the shores to protect them and the land from eroding. He and his children have a small foundation called Kallen Pokkudan Mangrove Tree Trust—a small foundation with a huge impact. I also have a group exhibition in Delhi, which opens soon. It’s titled, I Grant You My Freedom, running for a month from September 5, 2023 at Shrine Empire.

Sajan Mani, Stretched light and muted howls (detail), 2023, acrylic and serigraphs on natural rubber sheet, 70 x 42 inches

Do you have a few last words for our readers before we close the interview?

For underprivileged, working-class aspiring artists: It is difficult to sustain as an artist, but you should not give up. Fight back! Maybe the so-called gatekeepers and institutional frameworks (museums) keep you away for some time, but do not worry and do not look at them. We must create our own worlds, and our voices should be heard.

For All: Please come and dream with us for our collective futures!

In the end, it is art that we are making. Enjoy, dream, and dance!

Sajan Mani

@sajan_mani

Shristi Sainani

@shristi_sainani

Shrine Empire

@shrineempire

NOME Gallery

@nomegallery

Wake up Call for My Ancestors

@wakeupcallforancestors

Speaking to Ancestors

@speakingtoancestors

Galerie Melike Bilir

@melike_bilir

Shristi Sainani is a curator, designer, researcher, and writer currently based in New Delhi, India, where she functions independently. Her interest lies in dismantling and assessing core concepts of exhibition making, specifically focusing on Contemporary Art churned through the diaspora of the Global South.

She also writes poetry, having published three books in the genre, and has contributed to several art and architectural forums. Her independent research focuses on collections and architecture of private art museums. Shristi’s paper on inclusivity in museum spaces won the INSC Researchers Award in 2021.

Shristi is a formally trained architect. She completed her Bachelor of Architecture from the University of Sydney and her Master’s degree in Curatorial Studies from the University of Melbourne.