JOE GOODE

Amanda Quinn Olivar zooms in with her longtime family friend.

Portrait by Manfredi Gioacchini

Joe Goode was born in Oklahoma City in 1937. He attended the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles from 1959 to 1961. Over the past 60 years, his work has been shown in galleries from Los Angeles to New York, London to Tokyo. His work has been featured in museum exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art, The Museum of Modern Art in New York, The Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and many more. Goode lives and works in Los Angeles.

Interview by Amanda Quinn Olivar

Amanda: It’s very good to see you.

Joe: Nice to see you too, kid.

I want to delve back a little bit, but I’d love to know what you’re working on now, what’s exciting to you.

Ah... want me to show ya?

I’d love that.

OK—I’m getting ready for a show, so I’ve got all of this work up.

Fabulous.

I’ll give you a tour. I can show you my painting…

Untitled (Milk Bottle Painting 164), 2014, acrylic on archival board, 17 x 11.75 inches

Oh, that’s a beauty.

Did you see the milk bottle?

I did!

This one is called Vive la France...

Vive La France (Milk Bottle Painting 330), 2020, 20 x 16 inches

Is that a glass milk bottle on the bottom left? How did you attach it? [referring to Untitled (Milk Bottle Painting 239), below]

Untitled (Milk Bottle Painting 239), 2015,17 x 11 1/2 x 3/4 inches

Gorilla glue... very good [laughter]. This is another one. This doesn’t have a bottle... I just painted the bottle.

Untitled (Milk Bottle Painting 149), 2012, acrylic on canvas, 50 x 48 inches

When did you make that?

Around 2012... All right, you ready? OK, we’re going to do a drive-by... These are babies.

Untitled (Milk Bottle Painting 170), 2014, acrylic on canvas, 17 x 11.75 inches

Untitled (Milk Bottle Painting 263), 2014, acrylic on canvas, 17 x 11.75 inches

Oh, these are exciting!

You like 'em?

Yeah, I really do. Don’t you?

Agh.

Do you like them?

I did. I guess I’m tired of them now. I’ve been doing them for 50 years... That’s it!

You know, it’s funny that you said that. Because there were a few things I learned about you in preparation for our talk today. You said at one point, "I don’t feel like my work changes. I’ve been making the same painting for 50 years."

[laughing] Well that’s what I just said... didn’t I?

You did!

Here, this is pretty recent... It's a photograph of a milk bottle. It’s just a photograph blown up of a milk bottle broken on the floor of my studio and then I splasssshhhhhh it with paint...

Shattered Milk Bottle 15, 2009-2011, acrylic, archival digital print, 55 x 73 inches

Here’s more babies...

Untitled (Milk Bottle Painting 162), 2014, acrylic on archival board, 17 x 11.75 x ¾ inches

Untitled (Milk Bottle Painting 165), 2014, acrylic on archival board, 17 x 11.75 x ¾ inches

Untitled (Milk Bottle Painting 171), 2014, acrylic on archival board, 17 x 11.75 x ¾ inches

I love these, wow. Are they all milk bottles: painted and sculptural?

Yeah, they all have an image of a milk bottle one way or another.

How did you start working with milk bottles?

The idea came from having milk delivered on the front porch when [my daughter] Stephanie was a baby. I had gone out and was coming back to my house, and I saw them sitting on the porch, and it looked like they were kind of floating in air because different bottles were sitting on different steps... So it looked like, you know, 1, 2, 3 steps and it looked like one was in front of the other... So that’s kind of how I got the idea. That was the start of the milk bottle.

Was that the start of your career... when you started as an artist?

In my case, I kind of was always... you know, it’s hard to know when you’re a serious artist... when you start to be a serious artist and when you don’t, because I started drawing really early, when I was young. My father was a portrait painter. So I drew with him as a kid. So it just kept going and going and going until here we are, ya know?

Untitled (Milk Bottle Photo 10), 2004, sumi ink and photograph on washi paper, 26.5 x 25.5 inches

I didn’t know that your father painted.

Yeah... he was a good painter.

Did you start drawing and painting to be like him?

Sometimes I would draw. He would have a still life set up or something and I would draw, sitting next to him or something, but never paint. I never painted then, no.

When did you understand that you wanted to be an artist? When did that hit you?

I’m still workin' on that.

[both laughing]

I don’t think it ever concretely came to my mind. In one sense when you're a kid and you’re drawing, you always think you’re an artist... and it just never changed...

The kid in you.

That’s what being an artist is. That’s all it is... playing around. Having your own playground, you know? That’s what art studios are, just an artist's playground.

Let’s talk about Chouinard... Did you have a favorite instructor, someone who encouraged you?

Yeah. I did. His name was Bob Irwin. He encouraged you to do whatever you wanted to do. There was a freedom about... he never gave assignments, or anything like that. He didn’t tell you to come in and draw from the figure or stuff like that.

He [Irwin] knew that I had a house with Ed [Ruscha] and some other people in Hollywood... and we just called it 'artists studio.' That house originally had a chicken coop in the back, and it was enclosed so they [the chickens] could go in at night. Well, we cleaned that out and each one of us had a wall, and that’s where we first started making our paintings. When we were going to art school... I had a wall, Ed had a wall, Jerry McMillan had a wall, and somebody else did... and that was it.

Joe Goode, Jerry McMillan, Ed Ruscha, and Patrick Blackwell in the studio space they shared while in school at Chouinard, circa 1959. Photo by Patrick Blackwell. Courtesy of Joe Goode

All of you in the chicken coop...?

Yeah, but it was like a house in back of a house, except it was smaller.

I’d love to see that chicken coop now.

[laughing] Yeahhh... the last time I saw that property they had a big three-story apartment building on it.

Everyone knows you and Ed [Ruscha] grew up together... and Jerry [McMillan] was also somewhere in there...

Jerry grew up with us as well.

So the three of you met in school? Sorry to take you way back...

That’s all right. Yeah, I knew Ed before I met Jerry. I met Ed when I was about seven years old because we were both Catholics. Well, he was kind of a Catholic. His mother was very Catholic, so he had to go to church... and I was an altar boy. And Ed will tell you that he would see Joe walking down the aisle with the priest and everything... especially like a benediction or something like that and he [Joe] was carrying this incense. And he [Ed] said, "Man... I used to really idolize Joe because he got to do all that stuff."

[both laughing]

Really?

Yeah [laughter], that was in an interview someplace. I don’t know where it was.

So Ed just wanted to carry the incense?

He just wanted to be recognized. Ya know, he wanted to be a movie star [laughter].

And boy, was he! I think the two of you are so alike, yet so different... When you're raised with someone, the environment that surrounds you makes you the same in many ways... don’t you think?

That’s right. I think that’s true. Yeah.

Let’s talk about when you left Chouinard in '61. Were you using a camera at that time?

I think I was. I had a Twin Reflex Yashica camera, which is a cheap version of a Rolleiflex. It was a Japanese camera. I don’t know if you know those cameras or not, but... I had that and I took pictures with that.

Did you use your own photographs in your work at the time?

I don’t know that I did, because I didn’t have access to a printer or anything. It was a film camera.

I’ve always wanted to know about your gunshot and vandalism series...

Basically, it has to do with create-and-destroy and create out of destruction and then create out of that. It’s just a repetitive thing. In my mind, it just keeps going...

Untitled (Four Part Torn Cloud) (Artist’s Proof #1), 1972, five-color lithograph on arches paper in four parts, 44 x 60 inches

Right now, are you working on ceramics?

I have some being fired right now, yeah... They’re sake cups. I don’t make art out of these ceramics. Not to sell or anything... I just make these for fun. We use them in my house and I give them to people. I kind of made a conscious decision that I didn’t want to create a market for them. I’ve had shows of ceramics but it was of ceramic sculpture. And the sculpture you know, that’s different. But for these cups and stuff that I make, I just wanted to make something I could give people.

What is most important to you about the visual experiences you create?

It’s kind of... I don’t consider it important. I just don’t. It’s like I said; it’s just a playground. When I come out to make things, I come out in the morning and fortunately, my studio is right behind my house, so I just walk out my door and into another door... and so I can come out here in the middle of the night and look at something… It’s just so convenient. It’s just kind of like part of my house, ya know. So it’s just easy for me.

So it’s not work for you. It sounds like it’s never been work for you.

That’s exactly right. It’s just something I do for fun.

That's so lucky.

Yeah, exactly. I think so, too. And I’ve never, ever, um, disavowed that. I’ve always really appreciated it. You know.

Yeah.

When I used to see how my father used to work... he used to do signage for a department store. So he was working in what they called the 'display department.' Then he’d come home at night and do work. He’d do his own personal paintings and stuff. And it was so inspiring, you know? I’m sure that had everything in the world to do with why I wanted to become an artist. It was my father doing it like that, and... just sitting there in AWE, watching him take a pencil and make something look like something with it...

...and that’s where you got your work ethic, but made it into play... something that you love. Have you ever had a moment where you questioned your career?

Hmm, I’m just trying to think. Give me a little time... It’s been over sixty years [laughs]. There have been times in my life when I’ve questioned whether I’ve wanted to show my work, but I don’t think I ever questioned whether I wanted to stop doing it. I don’t know... It’s kind of in my blood, ya know.

There have been times when I’ve questioned showing with galleries... sometimes I’ve had bad experiences with dealers or something, and I thought I just don’t really want to do this anymore. Now, I'm in such a great place, the dealers I’m working with and everything, I really like... and I’m just thankful they're also really good. I’m a lucky boy. I have a really good gallery in Cologne that I show with. He’s doing a book right now... should come out in the fall or something.

You’ve got a lot on your plate, Mr. Goode!

Well, you’ve got to keep busy.

If you were going to collaborate with someone, who would it be?

RUSCHAAAAA...

...besides Ed!

[both laughing]

Nobodyyyyy...!

Have you two ever collaborated?

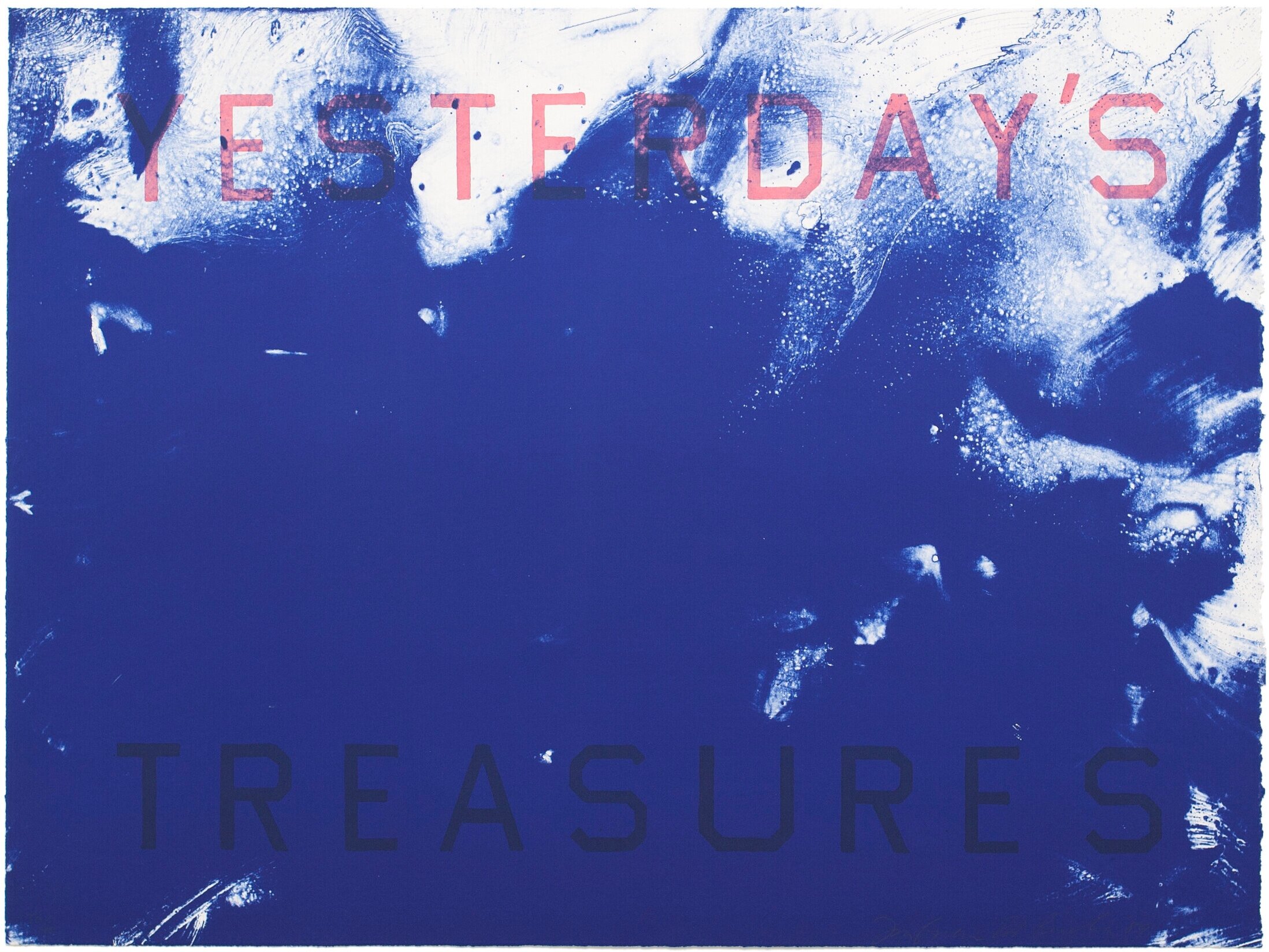

Yeah. We made a print. Do you know what it’s called? Well, I did a lithograph of an ocean with splashing water and everything, and then Ed lettered on top of it, in red letters. Well the ocean was blue, and in red letters, he wrote 'Yesterday’s Treasures' and 'Yesterday's’ is in red, and then as it goes deeper it turns almost black... ya know, like it’s going underwater, that kind of thing.

I’d love to see that if you have a photo.

Joe Goode/Ed Ruscha, Yesterday's Treasures, 1989, lithograph, 27 x 36 inches

Why don’t you come over and I’ll give you one.

You’re so... thank you, Joe. I’d love that. Are you sure?

Yeah! I'm 84 years old... What do you think I’m going to do with them in 10 years?

You’re doing great and sound like you’re 20... Would you ever collaborate with anyone else for fun?

I don’t know if that would work so well... just depends on who it is. Some artists I really like, but I wouldn’t want to work with them because they work in a completely different manner than I do. Some take forever to make a mark or something, and I’d have to wait 'til they did that... to do the next one. So, it has to do with things like that as well. It’s not just whether you like somebody or not. Ed is easy to work with because you know, I just do something on a plate and have somebody take it over to his studio and he’d do something and they’d bring it back and I’d add something more. That’s the way it works. It’s so easy.

You’ve had a brotherhood together, really.

Well yeah, we go back 60 years. The fact I’ve known him since I was 7 years old, ya know... it is like having a brother [another brother].

You know, everything was New York... Everything was New York and there was such prejudice against artists here in LA. I mean we were completely shut out of New York for the first 5 or 10 years. They just wouldn’t accept artists from LA. And Ed [Ruscha] kind of broke the barrier when he started showing with Leo Castelli. Because once you’re with... at that time if you’re showing with Leo, people could say anything they want and it’s not going to work, ya know. But that broke the barrier... they just didn’t want to accept our art there at all.

Circa 1970s: Dick Goode, Joe Goode, Ed Ruscha, Paul Ruscha. Courtesy of Joe Goode

Why did you choose LA instead of New York?

Oh, ha... that’s a good story! Well, Jerry McMillan had come home from art school over the Christmas vacation and we're sitting outside... He was getting ready to leave the next morning to drive back to California and so we were sitting there talking and God, I mean... We talked 2 or 3 hours, ya know, just talking about our pasts and what he was doing out there. He was trying to talk me into coming out there [to California], and I was hedging on it.

And so, after about 3 hours he said "Well I got to go... we got to leave early in the morning." I said OK... so I go to open my door and there was like 3 inches of snow on the ground and I couldn’t get the door open because of the snow. And so, finally, I said, "Drive up a little bit so I can get out." And so he did and I said, "Come back and pick me up in the morning. I’m goin' with you." And that was it!

Done deal.

Yep, that was it.

So you came out to LA and there were a core group of people here. Was one of those people Billy Al [Bengston]?

No, I didn’t know Billy at that time. This is before. I hadn’t even gone to art school yet. I just knew of people like Billy and [Robert] Irwin after I got into art school. But I didn’t know him personally at all until after I got out of school.

What did you do right when you got to LA?

I went to art school and in order to do that... I didn’t have enough money to support myself, so I had to get odd jobs and stuff. So I worked in different places, you know. Worked in a restaurant and parking cars, I did all kinds of things.

One more question about process, regarding your shotgun series... What went through your mind at the time: destruction and seeing through to what’s on the other side, but how did you come up with the notion to do that? And where did you do it?

Environmental Impact 16 Shotgun 16- Pink & Blue, 1980-81, oil on canvas, 54.25 x 96.25 inches

First of all, I used to... I had a shotgun. I bought this shotgun when I first moved up there [Springville, CA], and I really liked it, but then I took it one time and I went with this neighbor up there... We went dove hunting, and I shot this dove, and it was so amazing... The dove flew right over me and I shot it, and it fell right at the bottom of my feet, so I didn’t have to have a dog or go find it or anything... It was just at my feet. But the thing is, I picked it up and it was warm, still warm... and I almost started crying, and I couldn’t ever shoot anything again after that.

So I just had this shotgun sitting around, and I thought: Now I know a way I can look through this painting. So I put it down on the ground in front of my driveway, which was a dirt driveway, and then I opened the doors above my garage. I had my studio built and it cantilevered over the garage so I could park my cars underneath my garage, and then I used the inside of the garage for storage for paintings and stuff.

Anyway, I could open these doors that were like barn doors. And so then, I took these paintings and put them down on this dirt driveway, and then I went up and opened these barn doors and looked down on them... and shot them. And that’s how I did it. And then some, later, I just hung on a clothesline in the back.

Was it fun to shoot [the paintings]?

Well yeah, actually... half of what you say is true. The fun part was figuring it out. But shooting them was just like painting... I mean it wasn’t, there was no particular thrill in that other than just seeing the results... ya know. It was just a way of making it happen. It's like... some pieces I tore, some I shot. It’s just a way of seein' through.

Are you seeing through in your fire series too?

If you were looking at a painting I could show you how to do it, but you do look through fire. Fire’s not a flat flame. It has dimension. So you do look through it.

And then in my case, the idea for that came when I was sitting on my porch in Springville one night, and across the creek down the hill—there’s a creek going through, and on the other side of the creek I could see this light coming up from behind the mountains and I thought, Oh man, this is going to be a great moon. You know, I was thinking it was going to be a full moon, 'cause that’s where it came up usually.

And so I sat outside on my porch and I had a bottle of wine... and God, before I knew it I drank the whole damn bottle of wine, and it [the moon] never came up! You know, and so finally I went to bed and the next morning I got up and then I could see it was burning down below across the creek, but it was still burning a little bit right there... and that’s what it was, there was a fire. That’s where I got the idea, forest fires.

Joe Goode, Untitled (Forest Fire Painting #65), 1983, oil on canvas in three parts, 67.5 x 170.5 inches

OK, so thank you for telling good stories... I have one final question, and it’s a question that I ask of everybody. What is your favorite art accident... and how did it change your perspective or direction?

Well if I were to honestly answer that, I’d have to say almost every painting I do... I pour paint on top of a color I’ve already painted so it kind of at that point starts out as an accident, and then I just kind of work with that until I get it the way I like it... and let it dry. That’s what I do anyway. Yeah... [chuckle] hmm, ah... yeah.

I like that. Thank you, Joe Goode.

You’re welcome kid. It’s nice to see you. Come over and see me OK?

I would love that.

All right, hon... It’s really great talking to ya. Say hi to everybody!

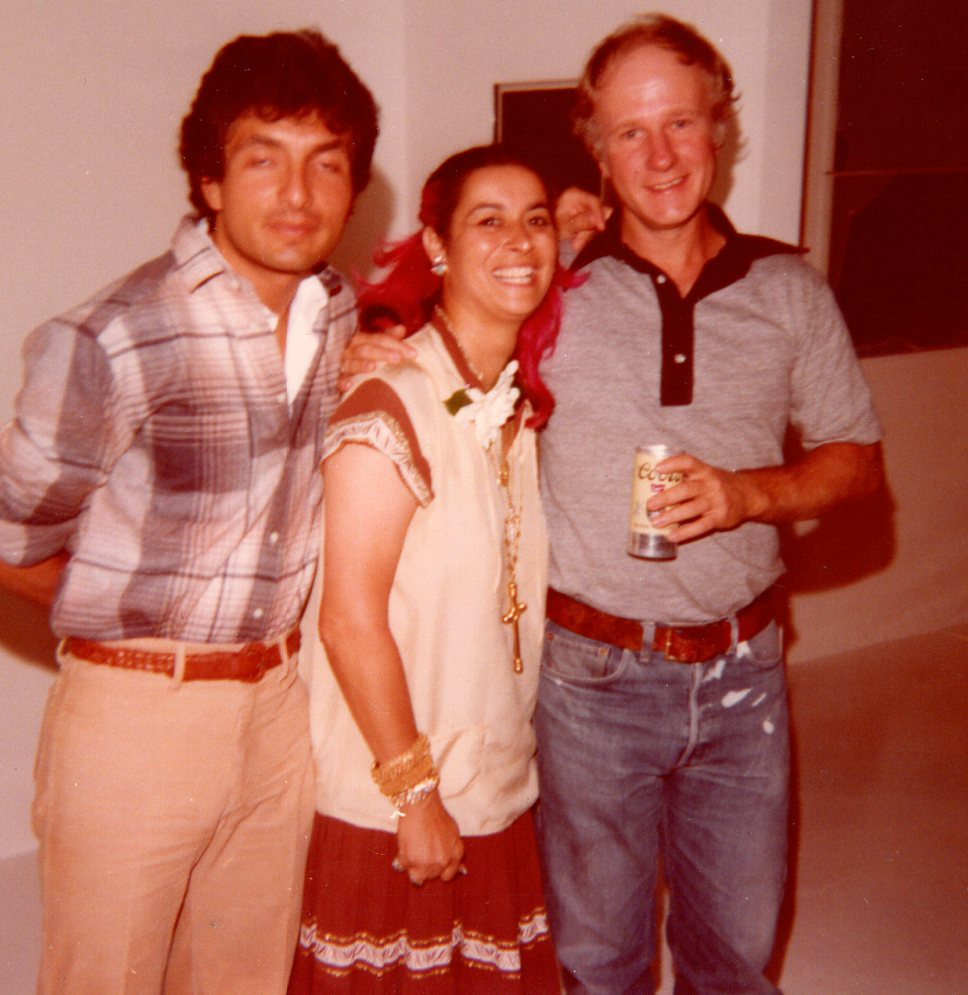

JOE GOODE CAPTURED THROUGH THE YEARS BY JOAN AGAJANIAN QUINN