March 2025

I Can’t Go on Living Like This

Joseph Beuys, 7000 Eichen (7000 Oaks). documenta 7 (1982). © documenta archive. Photo by Dieter Schwerdtle

A panel discussion about art, activism, media, comedy, and environmental responsibility—through the lens of Joseph Beuys and today’s cultural landscape.

Saul Appelbaum leads a conversation with The Broad curator Sarah Loyer and scholar Andrea Gyorody—co-curators of Joseph Beuys: In Defense of Nature—alongside Staci Roberts-Steele from the environmental nonprofit Yellow Dot Studios and Nato Thompson of the socially driven art consultancy Dreaming in Public. The discussion explores Beuys’ legacy, humor as a tool for activism, and the intersection of art, media, and environmental action today.

With an introduction by Adam McKay, founder of Yellow Dot Studios and director of Don’t Look Up, a satire on climate inaction.

Unless a movement draws on the energy and righteousness of the people, it is always vulnerable to being co-opted by the ruling status quo.

Popular support does not need to be the majority. Studies have shown that even less than five percent of a population becoming truly active is enough to change society's direction and affect real change.

But that five percent has to be willing to get arrested, beaten and shamed.

Why would anyone make that choice?

Seven simple words: I can’t go on living like this.

The civil rights movement in the US, Indian independence, and AIDS activists in the 80s all had this energy and direction. Unfortunately, with human-caused rapid climate change, the big oil companies have choked and, through ad dollars, bought our news system.

So, many people don't know we are less than ten years from catastrophic two degrees Celsius global warming. Those who know are already in the streets.

Once the reality can no longer be denied, hundreds of millions worldwide will flood squares, avenues, and the halls of government.

But this moment needs to happen now.

We are running out of time.

—Adam McKay

SnapGive, Yellow Dot Studios, 2023

Saul Appelbaum: Staci, will you introduce us to Yellow Dot Studios?

Staci Roberts-Steele: Yellow Dot is a nonprofit climate media company. We focus on combating the disinformation of fossil fuel companies, oil, coal, and gas companies. We use comedy in much of what we do, but not all of it. It's an excellent way to address the issues. Climate change is a worldwide issue that’s affecting every single type of person. It’s not one class or one demographic. Everyone gets and understands information differently. Comedy is a way to seep into the people who find it easier to understand science through entertainment or relate to humor more.

SA: What’s the role of hyperbole and narrative within this? Is the plotline even hyperbole anymore, or is it an unfathomably insane reality?

SRS: We’ll take a slice of life and spin it on its head. We put some extremes in it so that people can view it from a different angle. But what’s interesting is that it keeps catching up with us. Every time we do something crazy, it catches up. We made a video called SnapGive. It was about this couple fighting over where they had donated to the disasters. They realized that they had donated to the same disasters. There were so many disasters, and you were supposed to donate to that disaster. It’s about the absurdity of the world that we live in, and we're not talking about where the disasters are coming from. We're all panicked about how we're supposed to be a part of it.

The film Don't Look Up was the beginning of Yellow Dot. Adam wrote it in December of 2019. By the spring, when we were going to shoot, a lot had happened, like COVID. He had to change the whole script to make it crazier. Even looking at the film now, you watch it, and everything they're talking about is happening now. So yes, we have this extreme hyperbolic way of doing things, but we do it because it's rooted in reality.

Installation view of Joseph Beuys: In Defense of Nature at The Broad, Los Angeles, November 16, 2024 to March 23, 2025. Photo by Joshua White/JWPictures.com, courtesy of The Broad.

Installation view, Joseph Beuys: In Defense of Nature, The Broad, Los Angeles, November 16, 2024 — March 23, 2025. Photo by Joshua White/JWPictures.com, courtesy of The Broad.

SA: Before this panel, Sarah gave us a private tour of Joseph Beuys: In Defense of Nature. Thank you so much for that, Sarah. It was revealing because I’ve never seen a comprehensive display of Beuys’ multiples and how they tap into the performances, real politics, and social activism. Second, I was cracking up. A lot of work is like hyperbolic absurdist comedic relief in the context of serious art. There’s common ground here between Yellow Dot and Beuys’ approach. Staci, I love the billboard campaign that Yellow Dot did in Texas.

SRS: We used pictures of the effects of Hurricane Beryl in Texas. The billboard was a giant picture of a street, and a street sign was just peeking out of the water. It simply said, “You’re Welcome, Houston Love, Big Oil and Gas.” Things like that that we threw up without much planning. We didn't even tell the press. We put it in neighborhoods, took pictures, and put it online. What is comedic and serious relates a lot to Adam McKay's whole ethos when you look at The Big Short or Don't Look Up. It's taking those two sides of the coin and realizing how closely related they are.

Yellow Dot Studios Billboard Campaign, Houston, Texas, 2024

Yellow Dot Studios Billboard Campaign, Houston, Texas, 2024

SA: Sarah, the exhibit contains multiples about Beuys’ formation of the satirical political party and artwork A Political Party for Animals! I feel this binary here, too.

Sarah Loyer: It’s a thought exercise asking what would animals care about? What are the things that they would foreground in that political party? What’s their agenda?

It was essential to Andrea and me to bring Beuys' work to an audience and make it feel alive and contemporary because it's easy to put those objects in cases and have them detached from our current reality. It's challenging to take multiples and all these different kinds of objects, many of them found objects, some of which are literal garbage that he's manipulated in some small or large way, and translate that to an audience meaningfully. Humor plays a huge role. That was also important to foreground in the show. It's in almost every gallery. There are absurdist performances, like his contributions to Fluxus. It also extends to many other works, like digging up potatoes as a work of art, jumping in a peat bog, or these environmental actions that are seemingly banal but absurd and funny on their face. There's a lot of hyperbole in it.

Andrea Gyorody: Many of the multiples deal with communication as an idea. They embody a lot of ambivalence about art’s ability to “communicate or to have a message.” Having that in the work is essential when it’s a message or agenda-driven. Beuys simultaneously questions how it is possible to communicate politically in art. Can art function in that way? How would animals communicate their needs to us in a political party for animals? How would they be represented if they can't speak in a language we understand? Beuys proposed many absurdist gestures in the early '60s. He made this absurdist proposition to raise the Berlin Wall by five centimeters to make it better sculpturally. He is both nodding to the fact that so much of the architecture of fascism and other authoritarian systems is a sculptural or aesthetic problem, but also that dealing with that through humor and absurdity is maybe a better way of getting at those issues than in a head-on way.

He did both throughout his career. When he ran for office several times, he did it quite earnestly. Still, I also believe that he knew it was relatively unlikely and that by doing that publicly, he would push the role that art can and should play in society and the limitations that we put on art in allowing it to have certain kinds of influence and not other types, a certain amount of power, but not too much. The German press frequently discussed him as a jokester or a prankster. So, there was always this way of containing him under this rubric. Can we take him seriously? Are these gestures and statements real, or are they about an absurdist and artistic position towards society? There was always a question about that in Germany, and that part has not translated so much in an American context, where he's this incredibly self-serious person. There are many Beuys, but a serious Beuys and a prankster Beuys are part of the same persona.

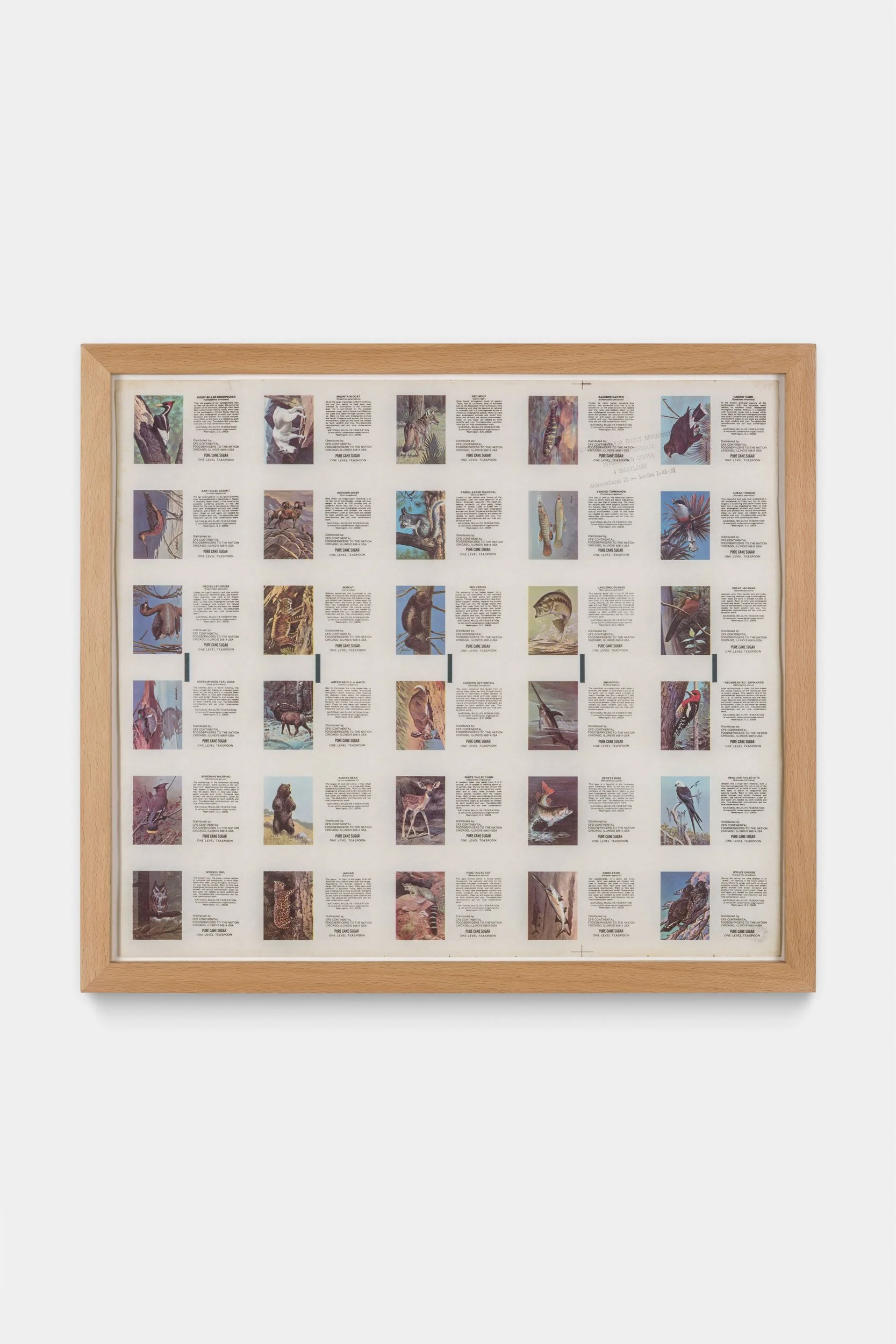

Joseph Beuys, A Political Party for Animals!, 1974. Proof sheet for sugar envelopes, with handwritten addition, stamped. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo by Joshua White/JWPictures.com

Detail, Joseph Beuys, A Political Party for Animals!, 1974. Proof sheet for sugar envelopes, with handwritten addition, stamped. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo by Joshua White/JWPictures.com

SL: 7,000 Oaks is an interesting example in Beuys’ work of something that does these two things simultaneously. He is pushing the institution of Documenta to do something extreme by going outside the museum and the museum's grounds, planting 7,000 trees throughout the city and placing 7,000 stone markers. It's this massive undertaking. It also significantly impacts the individuals living in the city, who take ownership of it. There’s this seriousness in the radical gesture that is a decentralizing of authorship. Andrea and I were both interested in this as well.

Planting 7,000 trees and accomplishing that is insane. It’s the scale of that. It was hard to get 105 done on public land in Los Angeles! We've considered this project to have two prongs based on Beuys’ original project. The first is, of course, the environmental cause of planting trees as a proposition, as an artwork. Then, the other is the social healing embedded in the original work, which Andrea foregrounded in her scholarship and has shaped how we've thought about the project.

Beuys piled all 7,000 stones outside of the museum on the public lawn. That was a visual one-to-one to the wreckage after World War II because Kassel, Germany, had been severely destroyed by Allied bombings as it was a German military manufacturing city. This callback to a wartime visual was a provocation that upset people. It was Beuys’ gesture to say, All right, you want this gone? Well, you have to plant every tree. For each tree that's grown, a stone will move. It forced the hand of the city.

We also thought a lot about that with Social Forest. We thought about the social and environmental healing that needed to happen here in LA, which led us to work closely with some Tongva Gabrielino advisors, local Indigenous knowledge keepers. The Tongva people are not federally recognized, so there is no communal land. It felt important to us to work with land that was publicly stewarded for this project.

Lazaro Arvizu Jr. playing the flute in Elysian Park, Los Angeles, 2024. Photo by Elon Schoenholz Photography, courtesy of The Broad

Hands cradling oak acorns in Elysian Park, Los Angeles, 2024. Photo by Elon Schoenholz Photography, courtesy of The Broad

Installation view, Joseph Beuys: In Defense of Nature, The Broad, Los Angeles, November 16, 2024 — March 23, 2025. Photo by Joshua White/JWPictures.com, courtesy of The Broad.

Nato Thompson: Beuys was so complex. He fabricated a mythology himself, and he was an operator. By the time he came to the United States, he was renowned, and people were skeptical of him because of his fame in the art world. It was like a Western European product. He was very savvy at manipulating the media to his benefit. He is also very media-conscious about who he is. I remember there was this fantastic interview. He got a lot of pushback at the Guggenheim when he did a talk. People questioned his mythologizing and not the hard-nosed real politics. It was in the era of anti-Vietnam War activism. People didn't want mythologies, but in some ways, they didn't want art. They didn't want something symbolic at that moment. As much as we credit Beuys with founding the Green Party as politics, the thing that he did more profoundly was to show that politics is myth-making.

And he embodied that. As for the work of Yellow Dot Studios and the gallows humor moments we are in, it’s tricky. I always feel like resting on raising awareness is a double-edged sword because today's riddle is that we know what causes climate change, but why didn't anyone stop or solve it?

SRS: We have solutions, but we're not using them or scaling them up. That’s precisely what you're saying. We know why it's happening and how to fix it, yet there's this weirdness in between where we do nothing.

NT: To connect the dots between Beuys and Yellow Dot, artists’ skill sets have been incorporated into marketing machines for everything, or symbolic language to produce meaning is now imbricated with power. People working in institutions, too, live in a mediated landscape perpetuated by a culture where any contradiction of power makes them easily vulnerable. But it also makes it difficult for those trying to produce with any distributive capacity to say anything controversial. We have these contradictions. We can call out power in Yellow Dot's work, but power is remarkably insulated from public opinion. It only takes looking at Black Lives Matter to show how the police departments have not changed much based on all that movement. Occupy Wall Street did not change Wall Street much. We’re in a moment where these contradictions make everybody look like a hypocrite. You say this, but nothing happens. You say that, but nothing happens. It puts us all in this demoralizing situation today. How do you navigate that?

We Are Scientists, Yellow Dot Studios, 2024

SRS: You're right. It's incredibly tricky. We're up against these vast power structures, and we live within them. Looking at Hollywood, how can we discuss sustainability when putting these massive productions together and playing pretend? What’s the purpose of that? Is that doing anything when spending all this money and time? It complicates our film and TV side at Hyperobject [Adam McKay’s production company]. It’s trying to get projects off the ground, and we have to deal with these big corporations that say, oh, no, that goes against everything we stand for. The amount of progress we've been able to make is discouraging in many ways because we're up against so much.

What is our role in all this? Is planting trees or making a film about the environmental crisis enough? We are this glue to culture, and every little act surrounding a piece of art, whether visual art or a movie, is about the conversations that come out of it. So, a role of this in my world, at least, is these actors. You must discuss that a hurricane shut down production on that press tour. You need to talk about what went on because of this fire. You need to connect these dots for people. Sometimes, our role is to take this art and this beauty or this darkness and glue it to the question of how this can affect change. The hope is that these cultural movements are the things that will eventually make a change. It just takes forever.

AG: Many works in the Beuys show that, depending on how you feel, that day could be depressing or hopeful. I took some friends through the other day, and we happened to catch a moment of this video of Beuys talking to people at Documenta in 1972, where he had set up this office for direct democracy. It was him sitting there for 100 days, and people would come in, and they could get pamphlets, chitchat, and learn about this notion of direct democracy. In that video, he talks about how we should pay housewives what we call universal basic income today to acknowledge their labor. I'm standing there like, it's been 53 years, and that is still a radical idea that people can't take seriously. It’s the idea that some forms of labor in our society go completely unpaid and undervalued.

On the one hand, you could say, “Wow, nothing’s changed in 53 years. What are we doing?” On the other hand, these ideas are still alive. From the get-go, Sarah and I asked how we would make Beuys relevant to an LA audience in 2024—25. That hasn’t been difficult because much of what he was talking about is still hyper-relevant and increasingly so. We opened the exhibition very close to the election, and we were installing it when Trump was reelected, which made us reflect on the antifascist aims in Beuys’ work and rhetoric—his rhetoric is particularly complex because, despite opposing fascism, he remains a figure associated with Germany’s fascist past. He still holds an authoritative position. How do we deal with all these contradictions in this exhibition, in this person, in his work? And what can we learn from them?

Joseph Beuys, Der Unbesiegbare (The Invincible), 1979. Poster, silkscreen on paper. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo by Joshua White/JWPictures.com

Joseph Beuys, Stimmzettel (Ballot), 1980. Ballot paper stamped. © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn. Photo by Joshua White/JWPictures.com

SA: Staci, in an earlier conversation, you mentioned how big businesses put environmental responsibility back onto consumers or individuals by emphasizing personal recycling rather than taking responsibility for implementing more significant structural change.

SRS: When I started thinking about climate and environmental issues in my lifetime, the ’90s into 2000s came to mind, when there was this idea that consumers needed to recycle and be conscientious of their carbon footprint. This was an important idea, but the reality was that the oil company BP coined the term “carbon footprint” in the early 2000s to shift the blame onto individuals. It was also a way to place responsibility on individuals with the directive “this is what you need to do” when, in reality, today, around 80 oil, coal, and gas companies are responsible for roughly 75% of greenhouse gases and 90% of carbon emissions.

As early as the 1970s, these companies knew that their activities were trapping heat in the Earth’s atmosphere, contributing to global warming and extreme weather. They hired scientists, understood the consequences, and actively covered it up. So, this emphasis on individual action is significant—it’s like a gateway drug. When you think, “I have an electric car now,” or “I’m eating more plant-based food,” those are great steps and should be part of the conversation. But the reality is that a handful of companies are still responsible for the majority of pollution today.

SA: A lot of the media and press for Yellow Dot put pressure on forcing the hands of large corporations to take responsibility.

SRS: To do something. It's funny when Sara talked about the trees and the rocks in 7,000 Oaks and how it put forth that we'll remove the stones when you plant trees. That's what many climate activists are doing with the proposition that we'll stop going in and blocking the US capital when you stop taking fossil fuel money and dictating legislation around it. It's all interconnected.

The First Honest Chevron Ad, Yellow Dot Studios, 2023

NT: We have an accountability issue regarding structural power because, for instance, many people's retirement funds make money off oil and gas. It's a lot of money, and mainly how the corporations are set up, nobody feels accountable. That Eichmann in Jerusalem thing where Hannah Arendt looked at the trials of Eichmann, looked at the Holocaust, and there was this guy who was in charge of a concentration camp. His alibi was that everyone was just doing their job, including himself. And that's America. Everyone's just doing their job. A lobbyist is just paying for a suburban home with his kids. Everybody's just incrementally part of the problem.

The way humans think in general is not in terms of statistics. We don't think in terms of big structural things. We always want someone to blame. We want a personality. That's how we tell stories. What do we do with this tribal human thing? How do we confront structural issues where no one is to blame?

Staci, we're talking about myth-making, right? For Yellow Dot, how do you tell a story about structural inequities? I get Amazon at my door all the time, but there's no way that I’m a hypocrite, right? There's a little chipping away where we make these little compromises that all add to something more significant.

SRS: That is the role of art and storytelling. If you said to someone, “Hey, you have to stop getting those Amazon packages because you're burning down rainforests,” they're going to be like, “What? No, thank you.” Whereas when you have this distance from it as an audience member, and we highlight an issue through a story that's maybe not even directly related, it does have a deeper effect. I think you're right. We live in this system where making these hard lines is impossible.

NT: We are in a very historically specific moment. The effects of social media and everybody being a media maker have produced a very complex political landscape for us, mentally, personally, and privately. It's all conflated into mediation. Everybody feels it. It's not just COVID. Social media in the collective psyche is unique in how we shape politics and how people understand their actions and reactions. I want to underscore that because art is a conversation around representation. Beuys said everyone's an artist. It's a mixed bag when that's true.

SRS: And the same with activism. The chickens have come home to roost on that one.

The Broad Museum

Joseph Beuys: In Defense of Nature

Los Angeles, November 6, 2024 — March 23, 2025

Saul Appelbaum holds a Bachelor of Fine Art from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, a Master of Architecture from Cornell University, and a Master of Fine Art from the University of Chicago. His work spans art, architecture, fashion, and media, with collaborations across major institutions, publications, and artists. He has worked with Harper’s Bazaar, Elle, InStyle, Vogue, Numéro, and L’Officiel, as well as cultural organizations such as Serpentine Gallery, The Broad, the Museum of the African Diaspora, the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, and the Kunstmuseum Bern. His art and design collaborations include Marian Goodman Gallery, Petzel Gallery, de Sarthe Gallery, and Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates. He has also worked with figures such as Tony Cragg, Ann Hamilton, Pope.L, Natalia Reyes, Diego Boneta, Mick Jenkins, and Adam McKay’s Yellow Dot Studios. Additionally, he has contributed to initiatives such as Nato Thompson’s The Alternative Art School, Rocco Castoro’s SCNR, Kids of Immigrants, and the Atlanta Art Fair.

Sarah Loyer is curator and exhibitions manager at The Broad. She curated Keith Haring: Art Is for Everybody (2023), the first museum exhibition of the artist’s work in Los Angeles, and This Is Not America’s Flag (2022), featuring over 20 artists critically engaging with the U.S. flag. She also led The Broad’s presentation of Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963–1983 (2019), organized by Tate Modern, for which she received a 2020 Curatorial Award for Excellence. Since joining The Broad in 2014, she has worked on numerous exhibitions. Loyer holds a Master’s in Public Art Studies from the University of Southern California and a B.A. in Media and Cultural Studies from The New School.

Andrea Gyorody is director of the Frederick R. Weisman Museum of Art at Pepperdine University, where she has worked to deepen the museum’s engagement with the campus community through exhibitions, programs, and academic outreach. Since 2021, she has organized a conversation series on art and religion, initiated a multi-year collections care project, and curated exhibitions, including the forthcoming Hildur Asgeirsdóttir Jónsson: Infinite Space, Sublime Horizons. Previously, she was the Ellen Johnson ’33 Assistant Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College, where she focused on diversifying the permanent collection and collaborated across college departments to develop programming in support of equity and inclusion efforts.

Staci Roberts-Steele is managing director and executive producer at Yellow Dot Studios, Adam McKay’s nonprofit climate media company. Previously, she was a production executive at Hyperobject Industries, where she co-produced Don’t Look Up, starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Jennifer Lawrence, and Meryl Streep. She also produced the Webby- and Ambie-nominated podcast The Last Movie Ever Made, about the film’s production. As an actor, she has appeared in Parks and Recreation, Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D., 90210, as well as in McKay’s Vice and Don’t Look Up. She is an alumna of Vassar College, Second City, and iO Chicago.

Adam McKay is an Academy Award-winning writer, director, and producer known for his sharp social and political satire. He co-wrote and directed The Big Short (2015), which earned him an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay, and Vice (2018), which was nominated for eight Academy Awards. His 2021 film Don’t Look Up, a dark comedy about political dysfunction in the face of global crisis, became one of Netflix’s most-watched releases and was nominated for four Academy Awards, including Best Picture. McKay first gained prominence as head writer for Saturday Night Live before co-founding the influential comedy platform Funny or Die. He has since expanded into climate activism, founding Yellow Dot Studios, a nonprofit media company focused on environmental storytelling and combating fossil fuel disinformation.

Nato Thompson began his career as a curator at MASS MoCA, where he organized large-scale exhibitions, including The Interventionists: Art in the Social Sphere, a survey of political art from the 1990s. He later served as chief curator and artistic director at Creative Time in New York, where he produced major public art projects such as Kara Walker’s A Subtlety, Paul Chan’s Waiting for Godot, Ramírez Jonas’s Key to the City, and Trevor Paglen’s The Last Pictures, while also organizing summits on art and social justice. He was a partner at artw ld, working with contemporary artists on high-end digital artworks, and collaborated with Philadelphia Contemporary on plans for a 21st-century museum in Philadelphia. He is currently the founder and director of the Alternative Art School, an online platform connecting visionary artists with working artists worldwide.