Dahlia Elsayed & Andrew Haik Demirjian

Souvenirs from the Future (installation view), Arab American National Museum. Photograph by Houssam Mchaimech.

“We were tired of so many dystopian, bleak future visions. We want to think about joyful possibilities, about dancing in the revolution.”

—Andrew Haik Demirjian

Amanda Quinn Olivar speaks with artists Dahlia Elsayed and Andrew Haik Demirjian about their installation ‘Souvenirs from the Future’ at the Arab American National Museum in Dearborn, Michigan.

Dahlia Elsayed is an artist and writer. She uses painting, installation, and sculpture to make fictional landscapes that refer to east/west marginality in pictorial spaces. Her work is based on pairing diasporan narrative with a terra firma, connecting internal and external sense of place and creating myth pictures for placelessness. These allegorical landscapes use a symbolic vocabulary rooted in cartography, comics, and cosmology to make visual narratives that tell unreliable oral histories and anticipate alternate futures. Dahlia’s interest in these themes stems from her experience of displacement over multiple generations of her family. These involuntary movements from continent to continent, with little belongings but much in story, have formed how she thinks about place and lore. Dahlia connects the material and concrete to the ephemeral shapes of personal geography.

Andrew Haik Demirjian builds linguistic, sonic, and visual environments that disrupt habituated ways of reading, hearing, and seeing. His interdisciplinary artistic practice examines structures that shape consciousness and perception, questioning frameworks that support the status quo and limit thought. The works are often presented in non-traditional spaces, including multi-channel audiovisual installations, generative artworks, video poems, augmented reality apps, and live performances.

Souvenirs from the Future (installation view), Arab American National Museum.

Amanda Quinn Olivar (AQO): Your new installation presenting “artifacts” from a fictional Southwest Asian North African (SWANA) inspired city from the future is fascinating! What does “Souvenirs from the Future” mean to each of you, and what are you communicating?

Dahlia Elsayed (DE): Souvenirs refer to tangible, material objects with special meaning. We were thinking about what objects are meaningful over time and space - ritual objects, particular household objects, garments; what are the things we hold dear and resonate with?

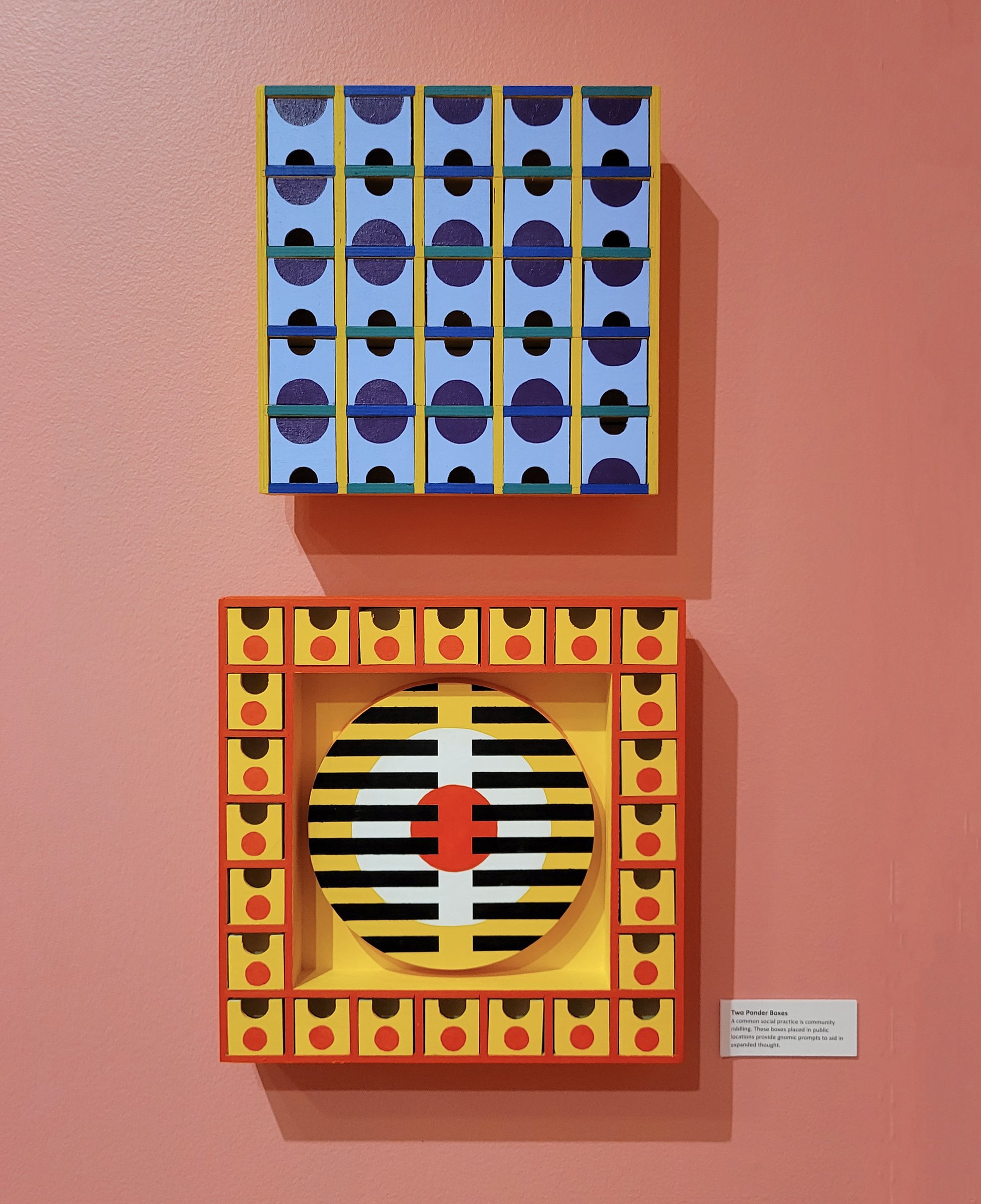

Objects tell stories, and we were interested in making objects that communicate the values, desires, and beliefs of Mustaqbaaahpolis as a complete city in the future. Like a board game loosely based on backgammon called A Game for No Winners or a ceramic Fret Bowl to release your worries into.

Andrew Haik Demirjian (AHD): The show also intentionally distorts our notions of linear time. We used an exhibition format that typically has a viewer looking back, but in this, someone is looking at objects from the future and thinking about what could be. We wanted to create the experience of a different feeling of time. So there are calendars that don’t use numbers to count, vision stones for periodic trances, and a soundtrack that floats overhead from the Sound Lamp that has music composed for the space that uses traditional SWANA instruments mixed with strings like an Uum Kulthum record but stretched to extreme durations that creates this kind of hovering, vibratory, atemporal feel.

We wanted to create an experience of time that doesn’t come from a scarcity mentality, a different way of thinking than reducing everything into a transactional ‘time equals money’ experience. We followed that thinking to consider what leisure and daily rituals would be like in a world without pressing ‘to-do’ lists.

Souvenirs from the Future (installation view), Arab American National Museum.

AQO: Talk about the origin of this project and the research involved.

DE: The project was a few years in the making - although we didn’t know what form it would take. Research is a big part of our practice; we went to Morocco, Armenia, Lebanon, and Egypt for this project. We still have family there and visit as often as we can. Still, the last few trips were more focused on looking at collections of historical sites and objects, thinking about how items are displayed and the institutional language they are presented with.

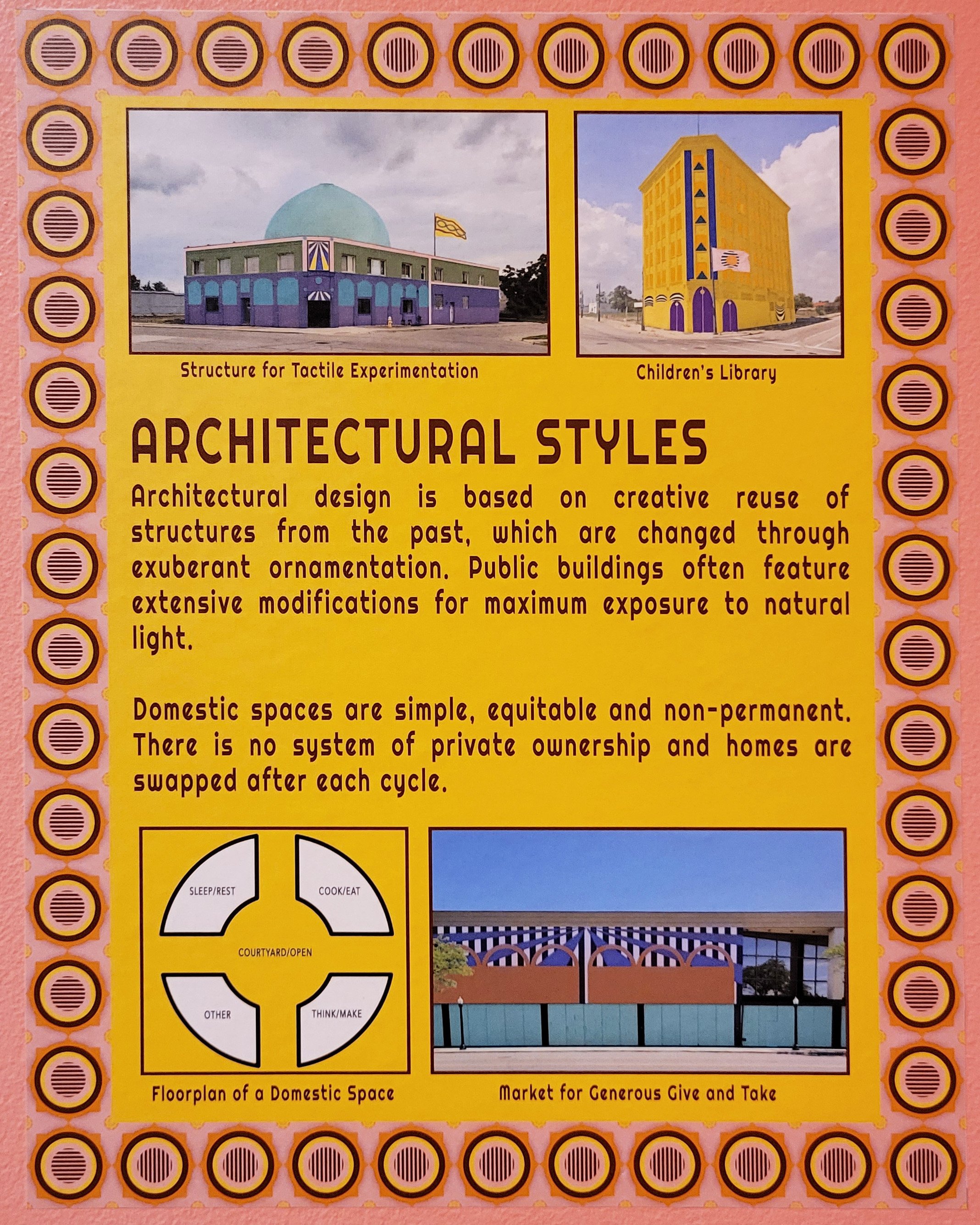

AHD: That is a significant element of Souvenirs from the Future. The labels and the wall text are an integral part of the art. We used the commonly understood formats of identifying labels and how the public engages with reading exhibition text as an extension of the art objects.

AQO: What attracted you to working with speculative fictions in your art?

DE: I like thinking about the simultaneous what-ifs, the idea that there are other ways of being besides a scarcity, precarity, and tragedy model. Working with speculative fictions enables perceptive shifts that can tap you into more liberated ways of existing.

AHD: Also, I was reading and re-reading some of Mark Fisher’s late essays like ‘Acid Communism’ and ‘The Slow Cancellation of the Future’ and was inspired by his writing about desire in a postcapitalist future - what does that look like and why shouldn’t it be there? So, these ideas were also mixing with many of the ancient civilization lectures that we were listening to. Some of the ideas for ways that people were keeping time were fascinating. All of these things started to interact together.

Souvenirs from the Future (installation view), Arab American National Museum.

AQO: Is working together a new experience for you? How did you approach this project collaboratively?

DE: We both have active individual practices but have collaborated for quite some time. Our first one was at Locust Projects in Miami, where we lived in a tent in the gallery under surveillance for 48 hours (in a great full-circle moment, we are working on a collaborative project for Locust Projects in their new building).

AHD: Although we work in different media, collaboration often makes sense because we have common conceptual interests: language, time, sensory experience, and pattern. The collaborations are interesting because working together informs our individual work, too. Collaboration also lets us create projects that are much bigger in scale than we could do individually.

AQO: An experimental use of language connects both of your practices. Are there new approaches to working with language in this piece?

AHD: Dahlia has an MFA in Writing, and I have a music background working with poetry and songwriting, so we have a shared love of language and poetry. A large part of this exhibition is all the writing in the show – the wall texts and descriptive labels are the conceptual underpinning of the whole thing and are just as important as the visual aspects.

DE: We wanted the language to communicate poetically and in surprising ways. The texts in the show also respond to the awful institutional tendencies of being didactic and overly academic in their wall text, which can suck the magic out of experiencing art.

AHD: Yes, we thought of the wall labels as experimental poetry in a gallery.

Portrait of Andrew Haik Demirjian and Dahlia Elsayed, exhibition inspiration in New Gourna Village, Egypt, 2022.

AQO: Talk about the museum’s Artist Residency Program and how you connect “Souvenirs from the Future” to Dearborn and Detroit.

AHD: The Dearborn area is home to the largest population of Arab Americans in the US, and the Arab American museum serves as its cultural hub in many ways. The residency opportunity is unique because it’s the only one specifically serving Arab/Arab adjacent artists and scholars. Being in residence there allowed us to engage with the community in meaningful ways, whether through a workshop, meeting people at a coffee shop, or engaging in deeper conversation with other artists/writers in the area.

DE: We also took inspiration from the architecture and decoration of the neighborhood surrounding the museum, so there are elements in the exhibit that people will connect to and recognize.

AQO: I’d like to talk about the significance of this artwork.

DE: If we can collectively visualize a kind, sustainable, equitable future, we can devise steps to take to get there. Souvenirs from the Future let us imagine alternatives to what’s not working now.

AHD: Also, we were tired of so many dystopian, bleak future visions. We want to think about joyful possibilities, about dancing in the revolution. A radical shift in the future should include tactile and sensory pleasure.

AQO: What is your current obsession?

AHD: We are obsessed with architect John Outram, his philosophies on space and pattern, and his ideas on a “landscape of symbols.” He is a visionary thinker.

DE: Besides my new obsession with making Yemeni chai, so many people are asking us for different elements from our recent installations, like the Shirt for Birdwatching, Rug for Foot Play or the Slippers for Quietly Ascending Stairs, so we are thinking about how to do that in meaningful/sustainable ways, to make the objects shareable and more accessible.

Souvenirs from the Future (installation view), Arab American National Museum.

Dahlia Elsayed, Amanda Quinn Olivar, Andrew Haik Demirjian, Armenian Museum of America, Watertown, MA, 2022.

Dahlia Elsayed and Andrew Demirjian

Souvenirs From the Future

The Arab American National Museum (AANM)

Dearborn, Michigan

Dahlia Elsayed’s work has been exhibited at galleries and institutions throughout the United States and internationally, including the 12th Cairo Biennale, Robert Miller Gallery, BravinLee Programs, The New Jersey State Museum, and Aljira Center for Contemporary Art. Her work is in the public collections of the Newark Museum, the Zimmerli Museum, the Johnson & Johnson Corporation, and the US Department of State, amongst others. Dahlia has received awards from the Joan Mitchell Foundation, the Edward Albee Foundation, Visual Studies Workshop, the MacDowell Colony, the Women’s Studio Workshop, Headlands Center for the Arts, and the NJ State Council on the Arts. She received her MFA from Columbia University and currently lives and works in New Jersey. Ms. Elsayed is a Professor of Humanities at CUNY LaGuardia Community College in Long Island City, NY.

Andrew Haik Demirjian’s work has been exhibited at The Museum of the Moving Image, The New Museum – First Look: New Art Online, Fridman Gallery, Transformer Gallery, Eyebeam, Rush Arts, the White Box gallery, the Center for Book Arts, The Newark Museum and many other galleries, festivals, and museums. The MacDowell Colony, Nokia Bell Labs, Puffin Foundation, Artslink, Harvestworks, Rhizozme, Diapason, The Experimental Television Center, The Bemis Center, LMCC Swing Space, the MIT Open Documentary Lab, and the New Jersey State Council on the Arts are among some of the organizations that have supported his work. Andrew teaches theory and production courses in emerging media in the Film and Media Department and the Integrated Media Arts MFA program at Hunter College.

Amanda Quinn Olivar grew up surrounded by art and artists, organically navigating toward curating & producing. She has collaborated with venues including the Cornell Art Museum, Skirball Cultural Center, Fresno Art Museum, The Brand Art Center, and the Bakersfield Museum of Art. Amanda produced the award-winning feature documentary on female directors, Seeing is Believing: Women Direct, and the play Paint Made Flesh. She received the HeArt award for her efforts benefiting nonprofit A Window Between Worlds, and serves on the boards of The Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, Axial Theatre, She CURAtes The Residency, Friends of Zandra Rhodes Fashion & Textile Museum, London, is a member of the Armenian International Women’s Association (AIWA), and a founding member of The Chimaera Project’s Board of Directors. Amanda was born and raised in Los Angeles, CA.

If you have the opportunity, do what you love —AQO

The Arab American National Museum (AANM) is the first and only museum in the United States devoted to recording the Arab American experience. Since opening in 2005, AANM’s mission has been to document, preserve and present the history, culture and contributions of Arab Americans.