FRANCIS BACON

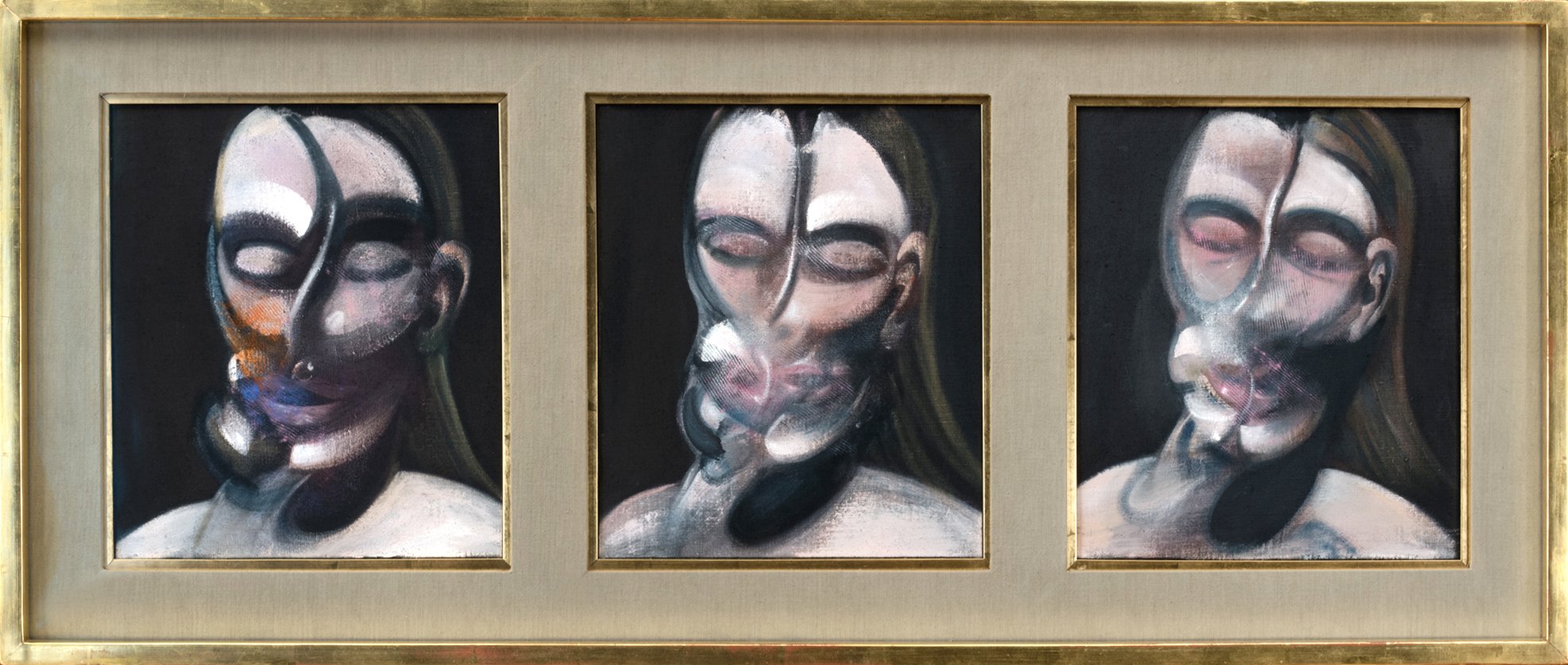

Francis Bacon, Three Studies for a Portrait (detail),1976, oil on canvas, in three parts, each: 14 x 12 inches

Per Skarstedt discusses Faces & Figures, a new exhibition of the artist’s masterworks.

Interview by Dan Golden

Francis Bacon was born to an English family in Dublin, Ireland, in 1909. He moved to London at the age of sixteen, and in 1927, Bacon traveled to Berlin and Paris. While Bacon exhibited his paintings within group shows during the 1930s, it was not until after World War II that his career as a full-time artist began. Bacon’s first post-war solo exhibition included the primary example of many works inspired by Velazquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1650, and showed his use of characteristic enclosing frameworks. It was these paintings of Popes which cemented Bacon’s reputation. Other series include portraits of contemporary figures, sphinxes, animals, and wrestlers. Later works were often in triptych, but the figures grew calmer and were set against flat expanses of color. Since his first exhibition in 1934, the artist has been exhibited widely.

It’s a pleasure to talk with you about this new exhibition. Can you provide a brief overview?

Faces & Figures brings together ten Bacon works from some of the most critical decades of his career, from the fifties through the seventies. We wanted to trace Bacon’s life through the lens of the people who inspired him, like George Dyer, Peter Lacy, Henrietta Moraes, Muriel Belcher. We wanted to emphasize the many ways Bacon explored the human form in general - exemplified by his self-portraits and popes - and why that makes him one of the foremost painters of the twentieth century.

Francis Bacon, Three Studies for a Portrait (detail),1976, oil on canvas, in three parts, each: 14 x 12 inches

How did the exhibition come about?

The desire to mount an exhibition of Bacon’s work was catalyzed by the excellent show at the Royal Academy in London—our aubergine wall color is even inspired by the crimson hue used in London. While that show focused more on his turn towards the animalistic, this exhibition really hones in on the personal. We are incredibly grateful to the private collectors who lent their works to this show and allowed it to come to fruition.

Francis Bacon, Seated Figure on a Couch,1959, oil on canvas, 78 x 55 3/4 inches

Francis Bacon, Seated Woman,1961, oil on canvas, 64 7/8 x 55 7/8 inches

Francis Bacon, Man at Washbasin,1954, oil on canvas, 59 7/8 x 45 5/8 inches

Re-evaluating Bacon’s work and influence from a current vantage point, can you share any key insights that come to mind?

Bacon was working in figuration at a time when it wasn’t necessarily in vogue to do so, and not only kept the tradition alive but moved it forward through his investigations of the human condition. As we see a resurgence of artists working in figuration today and a renewed appreciation for this mode of artmaking, one notices his influence on their work both conceptually and stylistically, and viewing Bacon’s oeuvre in this context today breathes new life into it. His use of friends and lovers as subjects creates a sense of community and place that resonates today as we grapple with the isolation of the last couple of years.

Francis Bacon, Three Studies for a Portrait (detail),1976, oil on canvas, in three parts, each: 14 x 12 inches

Your gallery in New York provides a unique viewing opportunity for Bacon’s work. How do you see the setting affecting a viewer’s engagement with the work?

The gallery is indeed unique in the way it offers an intimate viewing experience, and Bacon’s work—especially the smaller paintings—really benefit from this type of environment. We renovated the entire building last fall, including the gallery spaces, to give them a more modern feel, and these subtle updates make the paintings feel even more timely. The aubergine used for the walls provides a more meditative, quiet environment, which hopefully compels the viewer to linger a little longer.

Faces and Figures, installation view, Skarstedt New York

Faces and Figures, installation view, Skarstedt New York

Faces and Figures, installation view, Skarstedt New York

Bacon had a famously tumultuous life. His work, on the other hand (while conveying chaos and movement), feels quiet, elegant, and meditative. I’m curious to hear what emotions or reactions you have when reflecting on his paintings.

Both tumult and quiet exist in tandem in these paintings, and the longer one looks, the more both become evident. There’s a profound sense of pain and loss that comes through in paintings such as Figure in Movement (1972), painted after the death of George Dyer, which is deepened when viewed alongside Three Studies for a Portrait of George Dyer (on light ground) (1964) and the sense of infatuation and the possibility it conveys. Or the quiet understanding of his own mortality seen in Study for Self-Portrait (1979). Even a painting such as Seated Woman (1961)—where the fiery Muriel Belcher seems to be softened—shows how both the chaotic and the intimate can live side-by-side within Bacon’s work.

Francis Bacon, Study for Self-Portrait,1979, oil on canvas, 14 x 12 inches

FRANCIS BACON

Faces and Figures

May 4 — June 11, 2022

Skarstedt

20 East 79th Street

New York

All images courtesy Skarstedt New York