July 2025

Abbas Zahedi

Interview by Sascha Behrendt

Installation photography of Abbas Zahedi, Begin Again 2025 as part of Gathering Ground at Tate Modern, 2025. © Tate Photography (Reece Straw)

Abbas Zahedi shares his multi-sensory approach to his Tate Modern show, Begin Again. Set within the exhibition Gathering Ground, focused on the current environmental crisis and grief, Zahedi offers monthly communal support groups alongside sculptural and sonic installations activated by live tunings and reconfigurations during his year-long show. Here, he compares and contrasts it to his intimate nightclub installation, it’s your turn to be, where bodies, algorithms, and sound collide into new ways of being.

“Zahedi works with people and places to help process difficult emotions.”

— Helen O’Malley, Curator, Tate Modern

Installation photography of Abbas Zahedi, Begin Again 2025 as part of Gathering Ground at Tate Modern, 2025. © Tate Photography (Reece Straw)

Sascha Behrendt: You’ve described your Tate Modern installation Begin Again as a modular sculpture, sonic field, and site for resonance and communal attunement. What do you mean by these?

Abbas Zahedi: The installation operates across three registers: as a sculptural presence, a sonic environment, and a relational space. When I refer to it as a “modular sculpture,” I mean that the forms are not fixed — they’re designed to be disassembled, reconfigured, and reactivated over time. This mutability allows the work to evolve in response to its setting and the wider rhythms of the exhibition.

The sounds you hear in the space are sourced from recordings of the instruments being played — sounded, in a sense, back into themselves. These recordings are diffused through the gallery using resonators embedded in the architecture: in the walls, ceiling ductwork, even beneath the floor. So rather than sound emanating from a visible source, it filters through the skeletal infrastructure of the space. This generates an immersive acoustic field — not a harmony in the traditional sense, but closer to a tuning process, as if the installation is continually trying to attune itself to its environment.

Film credit: Zaida Violan, courtesy of the Tate Modern and Abbas Zahedi

An algorithm governs how the sounds recur and unfold — a sonic metabolism that loops. It’s not an echo of past performances; but a slow recalibration, a lingering resonance that shapes the experience. Crucially, the instruments remain playable — with bows, mallets, and hands. At present, the work is in a latent phase and has not yet been activated. That latency is integral. When a performance activation occurs, it alters the sculpture’s presence. It returns to stillness that is no longer neutral, it has been marked. For me, this capacity for shifts is central. It creates a structure where transformation is witnessed, not just imagined.

SB: So is the tuning, an attempt to arrive at a sonic equilibrium?

AZ: Yes — but it’s not equilibrium in the traditional sense I’m after. It’s more a process of tuning that never quite settles. The system is always reaching toward a moment of alignment, but it’s built to fall short — to collapse, disorient, and begin again. That collapse isn’t failure; it’s written into the rhythm of the work. At times, the sound becomes difficult, destabilised — something veers off frequency and unsettles the space. You might feel a moment of calm gathering, and then it unravels. That oscillation between coherence and rupture is where the work lives.

I’m drawn to that cycle because it mirrors emotional and relational states — the way we build toward connection or clarity, only to lose it, and have to start again. It’s not a linear journey, it’s a loop. An imperfect, lived rhythm. So, the sculpture is about modeling a condition: attunement not as a fixed state, but as an ongoing practice. That’s the deeper aim — to hold a space where imbalance can be felt, not just resolved.

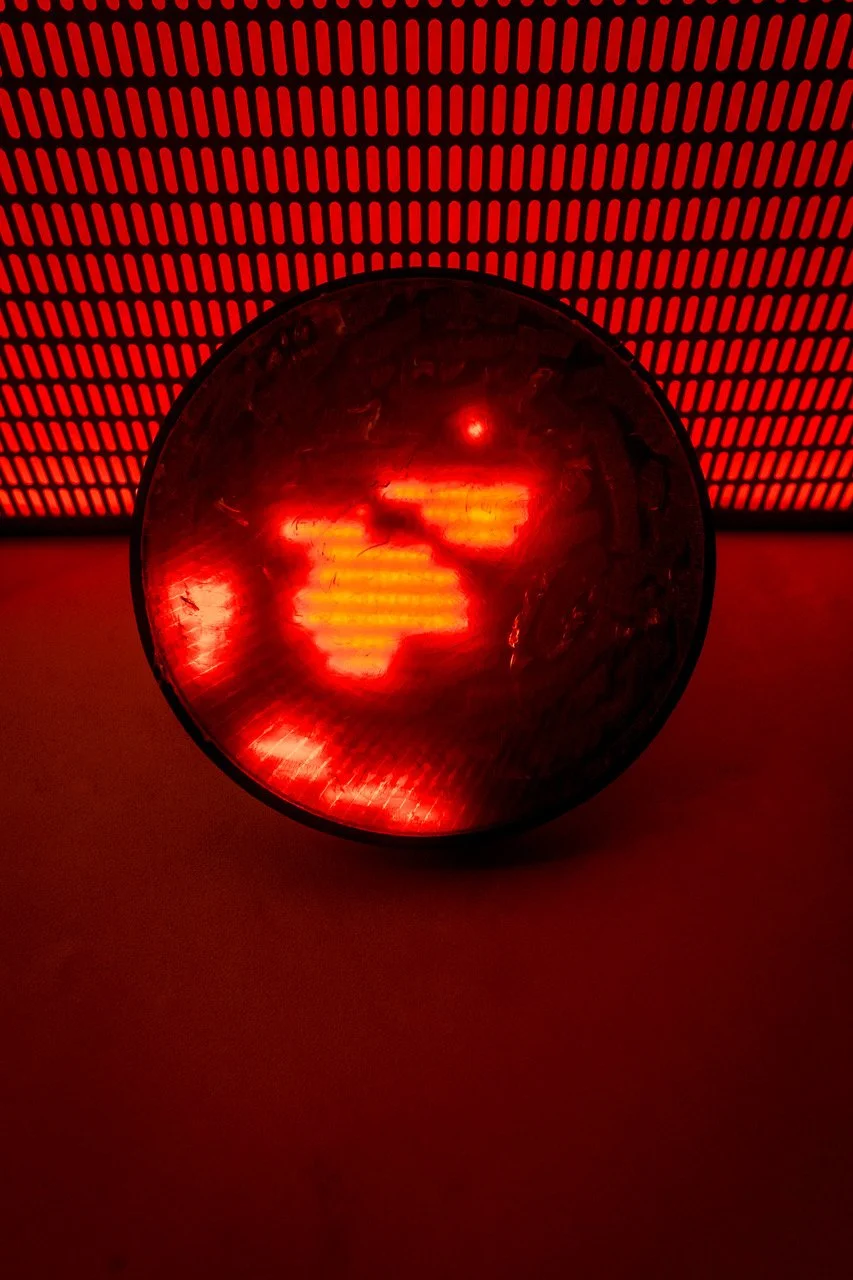

Installation photography of Abbas Zahedi, Begin Again, 2025, as part of Gathering Ground at Tate Modern, 2025. © Tate Photography (Reece Straw)

“Begin Again is not just about loss but about the potential embedded within grief—the possibility of beginning again.”

There’s also an ecological dimension. We can no longer rely on a stable, self-repairing nature. Our relationship to the Earth — like to each other — is now punctuated by thresholds of loss, by the consequences of assumption and overreach. The idea of a steady, nurturing ground has become more precarious. This installation doesn’t try to restore that fantasy, but to dwell within its absence — sonically, materially, and emotionally. To me, that’s where culture begins to do its deeper work: not in fixing what’s broken, but in allowing us to sit with rupture, to rehearse forms of care and listening that aren’t instrumental. That’s its quiet subversiveness — that it resists closure and remains alive to complexity.

Installation photography of Abbas Zahedi, Begin Again 2025 as part of Gathering Ground at Tate Modern, 2025. © Tate Photography (Reece Straw)

SB: We associate sound as being an individualized experience

AZ: Exactly. We often think of sound as private or internal — headphones, playlists, podcasts — but what I’m working with is a shared somatic field. Something you encounter through your own body, yes, but also in relation to others.

At the Tate, many people said they felt the sound physically — not just heard it, but registered it like a current moving through them. And as they moved through the space, that sensation shifted — not because the sound changed, but because their body tuned into it differently. The work meets each person where they are, quite literally.

There are over 24 audio channels dispersed invisibly through the space, there’s no fixed point of origin. You can’t orient yourself around a speaker.

Installation photography of Abbas Zahedi, Begin Again 2025 as part of Gathering Ground at Tate Modern, 2025. © Tate Photography (Reece Straw)

That dislocation isn’t just spatial — it’s relational. It asks you to move, to notice your body, but also to notice that others are doing the same. It’s a kind of acoustic commons — not in the sense of shared content, but in how people begin to attune together, to co-exist within a field of vibration.

SB: You also hold monthly public support sessions on the environmental crisis amidst your Tate installation

AZ: I thought carefully about what a year-long exhibition might afford — especially in relation to care, vulnerability, and trust. A one-year frame has become familiar in other parts of life: most master’s degrees are only a year long now, and many support groups or therapeutic programs ask for a similar commitment. That duration holds space for something to unfold — not just conceptually, but relationally. You need time to build trust, to return, to begin again.

So, I asked: what would it mean to shape a public program not around events or one-off engagements, but around that deeper arc? A space that people could return to, where the conversation isn’t starting from zero each time. That’s where the idea of a monthly support group came in — not as a public-facing add-on, but as part of the material language of the exhibition. In the materials list, I included “support groups” alongside metal, sound, and architectural elements, because these gatherings are integral to how the work lives in the space, and how it listens back.

SB: Especially as feelings do not fit neatly into the time boxes that we construct

AZ: Yes — much like the experience of art itself, and how galleries try to contain it, the support group pushes back against that enclosure. And not as a metaphor — but as a real, embodied format brought into the institution. It’s a difficult experience to quantify, and even harder to archive. This wasn’t about programming a new event each month, to keep things lively — it was about offering continuity, care, and depth. If you’re asking people to show up and open themselves — especially around something as vast and entangled as the environmental crisis — then you have to show up too. You have to keep the door open. And for me, that meant being there every month, no matter what.

“Art spaces become more than places to look, it is a way to experience — to witness a vulnerability of being”

The group becomes a kind of vessel — and each session follows on from the last. People who began as strangers start to carry each other’s stories forward. What emerges isn’t about any one person or even the artwork in isolation. It’s about building a ground — emotional, sonic, architectural — where something collective can take root. These feelings don’t resolve on a set schedule. But the repetition matters. The fact that it happens again, that it remembers, and allows you to return — that’s what creates the possibility for something to unfold slowly, to deepen.

Installation photography of Abbas Zahedi, Begin Again 2025 as part of Gathering Ground at Tate Modern, 2025. © Tate Photography (Isidora Bojovic)

SB: It felt inspiring and profound to hear accountants, teachers, and normal people from all walks of life speaking eloquently about their hopes and fears for the earth, to be reminded of other people's minds and hearts. It sounds cliche, but we don't get to do this in a free, trusting way, publicly

AZ: Yes, we don't have these kinds of structures really anymore — spaces where people can sit together without needing to perform, fix, or resolve something. It's strange because art is often positioned as the domain of things that are precious or exceptional — the singular object, the moment of aesthetic intensity. But maybe what feels most rare today is the opportunity to be open about how we feel. To be present, together, without needing to produce or consume anything. That, for me, is a kind of preciousness that art spaces can hold — if they allow themselves to.

That’s what shaped the support group structure within Begin Again. I wanted to rethink what a “public program” could be as a vital part of the work itself. It’s about shifting the dynamic so that even if someone doesn’t speak, their presence is active, not passive. Silence itself becomes a contribution.

That’s why we begin each session with shared silence. Not as a meditative gesture, but to create a shared space of tension. And then someone — anyone — breaks it.

Installation photography of Abbas Zahedi, Begin Again 2025 as part of Gathering Ground at Tate Modern, 2025. © Tate Photography (Isidora Bojovic)

SB: Do you feel a lot of responsibility?

AZ: Yes, 100%. Holding space in this way isn’t casual — it requires care, foresight, and a subtle, considered structure. Much of the safeguarding is invisible, but that’s part of the point. It’s about creating conditions that feel open and soft on the surface while being deeply intentional underneath. There’s an opening statement that I give at the start of each session that sets the tone — it explains the format, the ethics, and the ethos of the space.

SB: A tacit understanding from the start

AZ: Yes, an agreement that becomes gently formalised at the beginning. I start by identifying the recurring members: myself, psychiatrist Sally Davies (formerly my analyst), and several members of the Tate team, mostly the curators directly involved with the show. Each month, we also invite a different guest — an artist, thinker, or practitioner — whose role is simply to offer a provocation, a thought, or a gesture to help open the space.

We avoid a dynamic where one thread dominates or a single voice gets overly centered — what I sometimes call the “rabbit hole effect,” where conversation narrows instead of widening. The goal is to hold a space that doesn’t collapse into debate or resolution but allows for coexistence — so different emotional tones and lines of thought can remain suspended alongside one another.

I’m interested in a form of dialogue that allows this rhythm, or wave, where moments of sharing rise and then recede into silence, allowing space for things to settle. Then, something else can surface. That ebb and flow is really important. It gives everyone time to digest what’s been said, to feel it in their own body, to breathe, and to respond only if and when it feels right — rather than reacting out of pressure or obligation.

Installation photography of Abbas Zahedi, Begin Again 2025 as part of Gathering Ground at Tate Modern, 2025. © Tate Photography (Isidora Bojovic)

SB: Yet keeping the dialogue flowing forward is not easy, is it?

AZ: I’ve been fortunate to experience a wide range of group dynamics over the years — from clinical to community-based— and that’s where I began to understand that the rhythm of a group, the pacing of silence and speech, is itself the work. My background in medicine and training in psychiatry gave me a foundational sense of structure and safeguarding, but it was really through being on the other side — as someone in long-term, intensive treatment — that I started to grasp the subtleties. I learned how it feels when a group holds together well, and how quickly it can fracture under the weight of too much talk, too little trust, or a lack of care in how people are met.

SB: It is unusual for a museum to host this kind of format

AZ: I remain deeply grateful to the curators and to Catherine Wood, Head of Programming, for placing their trust in me. From the very beginning, I made it clear that I didn’t want to treat the gallery as simply a place for looking. I asked: What does it mean to witness, rather than observe? That shift—from passive spectatorship to shared presence—shaped the entire approach. The support groups weren’t an afterthought or outreach initiative; they were the basis of my invitation to do this show, as I had already developed this blended model of exhibition-making from the start of my practice.

There’s an ongoing idea in art that what makes something valuable is its separateness—its exceptionality, its distance from the everyday. But I think what feels most rare now is the chance to come together without spectacle, without needing to produce a reaction or result. So instead of stripping away function to elevate form, I’m trying to fold form back into the texture of use—into the rituals, rhythms, and needs that people carry with them. Part of this is about reframing what a cultural space can hold. If culture emerges wherever surplus allows for reflection, then what happens when that surplus is emotional or relational, rather than economic? That’s the territory this work moves through—where meaning arises not just from what is shown, but from what is shared.

SB: We talked about the inadequacy of the words ‘secular spirituality’, or whatever one to tries to call it. Do you think we are still searching for that phenomenon?

AZ: Within liberal, secular, and so-called progressive spaces, questions of metaphysics or meaning beyond the material are often sidestepped, as if admitting to them might unravel the whole framework. But evasion doesn’t erase the need — it just pushes it elsewhere.

In some ways, we’ve replaced the symbolic and spiritual of religion with cultural forms that don’t fully carry the same weight. Art, in this context, becomes a placeholder — a space where certain yearnings for coherence, transcendence, and collective ritual can flicker, but not quite find anchorage. And so we inherit this unease: culture wants to be autonomous and immanent, but it still bears the trace of its theological roots. What I’m trying to do in my work is to make room for that contradiction — not to solve it, but to hold it. I’m not interested in offering redemption narratives or spiritual templates. But I do believe, that people carry forms of grief, uncertainty, and longing that can’t be resolved through critique alone. And I think the gallery, when treated not just as a site of display but as a space of encounter, can become a container for those unresolved energies.

SB: So, what does that personally mean for you?

AZ: I think much of what we call contemporary art in the West — especially shaped by a Eurocentric, secular worldview— operates under the assumption that we’ve outgrown the need for metaphysics. That we’ve somehow progressed beyond collective ritual or existential longing. And I say that as someone who is very much a product of this contemporary condition. I don’t practice within a religious tradition, and I don’t claim a spiritual lineage in any orthodox sense — but I come from a highly enchanted beginning, and I carry with me a strong sense of what, in Hegelian terms, might be called spirit. Not spirit in a mystical or transcendental way, but as a lived, collective undercurrent — a force of presence, memory, and becoming, that moves through people and places, often without needing to be named.

In many liberal art contexts, there’s room for spirituality — but usually only when it comes pre-framed by heritage, cultural distance, or otherness.

SB: Art and spiritual practice as an exotic curiosity

AZ: What we’re dealing with here is not simply a curiosity about spiritual practices or cultural otherness — it’s the residue of a deeper historical logic, one bound up with a distinctly Euro-American, post-Enlightenment view of history: linear, teleological, and ultimately eschatological. In this worldview — whose scaffolding is as much Judeo-Christian as it is post-religious — time is imagined as a forward-moving arrow, ever progressing from superstition to science, myth to modernity, ritual to rationality. Anything that lies outside of this chronology is not only rendered obsolete but patronized — exoticized as a cultural artifact, rather than recognized as a mode of meaning still very much at work in the present.

This linearity governs not just how we tell stories about religion or culture, but how we structure knowledge itself. In medical school, for instance, you’re taught to trace the path from the four humors to penicillin to genomic sequencing — as if each step renders the last one redundant. To invoke humoral theory today is laughable in clinical terms, but that laughter conceals an act of forgetting: namely, that every system of knowledge carries with it a metaphysics — a worldview, a social imaginary, a way of relating to life, death, and the body. What gets discarded isn’t just outdated science; it’s a whole cosmology.

We do the same with spiritual practices in art. Once these practices are no longer tethered to organized religion or cultural tradition, they are either dismissed as irrational or safely domesticated into aesthetic categories: “the mystical,” “the shamanic,” or “the folkloric.” As long as these forms are quarantined within heritage or identity, they’re permitted to circulate. But the moment a secular subject begins to gesture toward the metaphysical — without institutional backing or cultural credentials — the discomfort sets in. The system lacks the vocabulary, so it reaches for containment or critique. And yet the need persists. The desire for rituals, for a collective grammar of grief — none of that has disappeared. What’s shifted is the ground on which it all used to rest. For much of the liberal-progressive worldview, “nature” became the last standing surrogate for metaphysical cohesion — a kind of green-washed theology. We may have abandoned God, but we held fast to the Earth as a symbolic reservoir: provider, witness, balm. Nature became the placeholder for all that secular reason couldn’t quite resolve. It was the last shared site of enchantment.

But now nature itself is unstable. Climate collapse has made it unfit for symbolic outsourcing. We can no longer project transcendence onto a world that is itself unraveling. And so the absence returns — not as a theological question, but as an existential one: what now holds us together? What do we gather around when even the ground is giving way?

This is what my work is wrestling with — not as illustration but as infrastructure. The piece isn’t just a sculpture or a soundscape. It needs time, recurrence, unpredictability, support groups, somatic rituals, and shared silences. Because I’m not trying to represent the crisis — it’s to ritualize our encounter with it. Not to aestheticize collapse, but to hold space within it.

SB: You challenge the old terms and frameworks which is so necessary for art grappling with wider environmental and societal shifts now

AZ: Coming into art from medicine — and from years of instability, including periods of practical homelessness — means I don’t take the art world’s assumptions for granted. I wasn’t inducted into a system that taught me to see art as a commodity, something to collect, display, or leverage for status. For a long time, I was exhibiting work while living between temporary spaces. So the idea of art as domestic décor or investment just wasn’t in my frame of reference. It wasn’t even legible to me. What that gave me, though, was clarity: that art had to be more than an object — it had to be a site of relation, a holding space. A way to move through grief, transition, and uncertainty — and to connect across social and emotional thresholds that weren’t otherwise being acknowledged. For me, making work wasn’t about building a career; it was a survival strategy. Something had to hold what wasn’t being held elsewhere.

That’s still the foundation for me. Even as my context has shifted, that early urgency hasn’t left. I’m not trying to position my practice within a market logic or historical lineage. I’m asking whether the work can host something real — something needed — in the moment we’re living through. That’s the measure that matters to me. Can it carry people through or hold something that might otherwise go unspoken? That’s what I keep returning to.

SB: So that difficult journey still informs your art.

AZ: Part of that journey has been about recognizing the structures of meaning I came from. Growing up in a religious household, meaning was inherited — passed down, protected, and carried forward. There’s a sense of vertical transmission in that: you don’t choose meaning, you receive it. Later, through philosophical inquiry, art school, and making work, I encountered a different model — meaning as something you generate from the ground up, through experience, material, and relation. That’s the classic position art tends to champion: meaning from below. It’s embodied, immanent, performative. But what I’ve come to is a need to hold both registers — without necessarily believing in them — but with a sensitivity to what each one offers, and the conditions that give them shape.

In my installations, I try to reflect that. I work with ceiling height, suspended objects, vertical scales — not just for effect, but to suggest that there’s still a ‘beyond’ worth invoking, even if we don’t name it. At the same time, the work remains grounded: in the body, in breath, in shared space. The art space, for me, is one of the last public environments where we can collectively examine how meaning is made — not just received or consumed, but interrogated.

SB: Yes, and we experience that in your Tate show

AZ: I have two works in London right now that occupy opposite ends of a spectrum — one high up at Tate Modern, the other underground in a nightclub in the center of town. The Tate installation is ambient, designed around resonance and collective support. The nightclub piece, it’s your turn to be, curated by Bianca Chu as part of her Nocturn program, is breath-driven, visceral, rooted in the physical intensity of sound systems and shared movement. They operate at different frequencies, but they remain in dialogue. One invites stillness and reflection; the other, rhythm and trance— a choreography of presence at different altitudes. Both works explore how meaning and connection are shaped by environment. Whether through silence or bass, rest or repetition, they offer ways to gather — not always to understand, but to attune.

SB: Chu talked about the club as becoming through your work a ‘cybernetic’ or ‘sentient body’. Would you explain what this means?

AZ: Yes, that same dialectic — of meaning from above and below — applies just as much to how I engage with institutions. Art spaces, especially within this Euro-American canon, tend to inherit a kind of clerical structure. They distribute meaning from the top down, like ecclesiastical authority dressed in minimalist architecture. The artist, in this frame, becomes something like a minor prophet: granted space, given a voice, but expected to speak in tongues that align with institutional decorum.

I’ve always found myself more attuned to other terrains — music cultures, diasporic gatherings, nightlife infrastructures — places where meaning isn’t handed down but improvised in real-time. There’s no manifesto on the wall in a club toilet, but there might be a voice note looping through the speaker, misfiring with enough distortion to suggest something more honest. The club isn’t a utopia, but it remains one of the last surviving zones where bodies cohere around rhythm instead of rhetoric. That, to me, is a serious cultural proposition — not decorative, nor supplemental.

Gourmet Word Salad/Studio Cubicle 2 Visual by Abbas Zahedi, installation view, NOCTURN [03] it’s your turn to be, feat Abbas Zahedi Photo: Graham Turner. Sonic Transmission mixed by Abbas Zahedi includes a reading performed and selected by Bianca Chu, excerpt of A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology & Socialist-Feminism in the Late Twentieth Century by Donna J. Haraway [1991]

In Nocturn, I was thinking through that proposition: what if the club could serve as a kind of cybernetic host — a sentient system where data, bodies, memory, and material all feed back into each other? Live-generated visuals, DAO readings in the toilets, sonic transmissions bouncing off the walls — none of it was meant to signify in the clean, legible way the gallery demands. Instead, it asked people to feel their way into meaning, to co-generate experience through proximity, movement, and repetition. It’s ironic that what the gallery calls “relational aesthetics” is often just another formal device — whereas in a club, relation is the premise. You don’t go to the dancefloor for critique; you go because it’s one of the few places where the social body still pulses with collective time. And so, by moving between these spaces — between Tate and Nocturn — I’m not just shifting registers. I’m drawing a line between two economies of attention: one that demands coherence, and one that allows for breakdown, distortion, fugue. Sometimes the most sentient space is the one where no one is explaining themselves - especially when we’re wrapped within a sound system that is second to none.

SB: A bespoke Martion Audiosysteme from Berlin.

AZ: Yes, Martion Audiosysteme is among the most respected in the world — signaling what’s still possible when sound is taken seriously, as a spatial force capable of shaping collective experience. In a space like that, you don’t just listen — you tend to submit. The sound moves through you, and overrides your individual signal. It’s less like being at a performance, and more like being wired into a communal nervous system.

That’s why I installed the visual feedback discs in the ceiling — or what becomes the ceiling once we’re below ground. When you descend, spatial logic inverts and that inversion felt crucial. These discs act like externalized organs — tracking breath, heat, environmental data — and translating that into visual signals that mirror the crowd’s presence. It’s a diagram, but also a monitoring system — visualizing a space that is never still, and then outputting breathwork patterns that can help you to attune to the shifting vibe of the club.

This is where the cybernetic language enters: not as a techno-fantasy, but as a recognition that everything in that room is responding to everything else. The people are modulating the system; the system is modulating the people. The room becomes a kind of social sensorium — elastic, reactive, and alive. And this isn’t just about signal feedback in the engineering sense — it’s behavioral, emotional, and spatial. A club like this hosts experience, and it metabolizes it. In an age where most social feedback is flattened into algorithms and metrics, to be part of a living loop — one that breathes with you is no small thing. It’s a reminder that even in the depths of our mechanized moment, we’re still relational creatures, still looking for resonance in the dark.

Film credit:,Abbas Zahedi, courtesy of Nocturn and 17 Little Portland St.

SB: How would you describe your reactive discs placed just above eye level?

AZ: They’re the size of a vinyl—12 inches—and I hand-carved each one from transparent Perspex, etching grooves into the surface so they act as textured lenses. The distortion they create is visual and spatial. As projections hit them, the image bends, warps, and layers itself, generating a tactile atmosphere. Each disc becomes both a sculptural object and a live interface—something not just to be seen, but felt.

Unified Respiration Device (URD prototype), installation view, NOCTURN [03] it’s your turn to be, feat Abbas Zahedi, curated by Bianca Chu, at Little Portland Street, London. Prototype Fabrication & Programming: Tom Pain. Photo: Graham Turner.

SB: You’ve linked them to sensors all around the club

AZ: Yes, they’re connected to a network of sensors —tracking everything from sound levels and BPM to room temperature and crowd density. We even factored in data like drink orders. All of this feeds into the visuals, turning the discs into live responders to the mood and motion of the space. It’s not just reacting to music—it’s attuning to the full atmosphere.

SB: Ha!

AZ: Mapping the vibe means registering more than just sound—it’s the heat, the density, what people are drinking, how they move. It becomes an ambient portrait of the crowd’s collective state. I wasn’t aiming for precision but for a system sensitive enough to respond to the emotional and energetic shifts as the night unfolds.

SB: Your idea of vibe-metrics

AZ: The whole idea of “vibe-metrics” came out of conversations with Bianca and the team—it was a shared inquiry into how we might embed responsive anchor points that could shift with the energy of the night. My decision to incorporate breathwork patterns came from that same impulse: tuning into subtle, often overlooked rhythms.

The algorithm behind the visuals was loosely inspired by ecstatic breath rituals—particularly the Sufi concept of the seven ascensions, which use the breath to move toward transcendence. There are overlaps with Buddhist practices too. I translated aspects of that into a non-linear system that could read shifts in the environment. So, the discs don’t just respond—they invite a kind of atmospheric meditation. You can engage consciously or just absorb it. Either way, it holds space for movement between presence and drift, which felt right for that context.

SB: So, you’re shaping the immaterial, the intangible, treating it as a material in itself.

AZ: There you go!

SB: The art you are creating within spaces such as at the Tate, looks deceptively simple, but it's not. It feels part of a wider conversation that's been going on for a while, especially in the US, asking, ‘What are art museums for? How are they evolving to meet mixed societal needs?

AZ: Yes. The idea of ‘pure’ art—of a disinterested aesthetic experience detached from social or material conditions—is not some neutral ideal; it’s the outcome of a particular historical and institutional construction. It assumes a viewer who is autonomous, contemplative, and somehow removed from the entanglements of life. But that figure is a fiction—one rooted in specific traditions of modernity that tend to erase the social, economic, and emotional structures that make any experience possible in the first place.

I don’t make art in that lineage. My work isn’t trying to rise above the world—it’s embedded in it. It’s shaped by grief, tension, collective presence, and the need to find or build meaning in conditions that don’t always support it. I see aesthetics as lived processes—something that happens between people, in time, through relation, friction, care, and participation. It’s not about crafting a spectacle, but creating situations that can hold people differently, even if only for a moment.

That’s why I’m often indifferent to the intellectual, academic, or market logics that dominate contemporary art spaces. These systems can isolate the work from the energies and communities that gave rise to it. They convert culture into content, and content into capital. So, for me, the question isn’t just what a museum is for, but what kind of time and attention it makes possible. What kind of bodies it expects, what kinds of needs it allows in, and what forms of care it can sustain. That’s what I’m working with—whether through breathwork, sound, collective silence, or support structures. I want to create spaces that don’t just present art but hold people. That doesn’t just show culture, but allows something cultural— live and shared—to actually take root.

SB: And with that opening up and re-purposing old hierarchical or didactic-based spaces.

AZ: Yes, the fact that these two works unfolded in parallel—one at Tate Modern, the other in a London nightclub—captures something essential to how I try to think about space, power, and presence. They operate at opposite ends of a cultural spectrum, but for me, they’re tuned to the same frequency: how can a work reshape the atmosphere it enters, not by imposing meaning, but by surfacing what might already be latent?

When Catherine Wood said to me, “It feels like this has been here forever,” I took it as something deeper than praise. It wasn’t about permanence—it was about resonance. That sense that a work has folded itself into the architecture, into the institutional memory of a space, without needing to declare itself. It’s a sign that the tuning has worked. That the piece is not just housed by the institution but has started to hum through it.

The Tate, of course, is part of a long lineage of museums shaped by Enlightenment ideals—spaces built to organize knowledge, instruct the viewer, and stabilize value. And while that scaffolding persists, the team there, particularly Helen O‘Malley, sees an opening—or maybe a fracture—where different kinds of engagements can surface. What I’m trying to do isn’t about confrontation. It’s more of a slow bend. A re-tuning. Like taking a familiar instrument and playing it in a way that unsettles its original pitch.

The club work was the counterpoint, and not just in form. In London right now, post Covid, club culture is under real threat. Spaces like the one we worked with are becoming rare and difficult to access. What’s at stake isn’t just nightlife, but a whole infrastructure of embodied sociality. These are places where people gather not to consume, but to enter a different consciousness. That mode of being together is disappearing—and with it, one of the few remaining architectures for collective attunement outside of market logic or institutional gatekeeping. For me, these two projects weren’t opposites. They formed a kind of feedback loop. At Tate, the work emerges from listening, from the long arc of emotional time. In the club, it emerges from the effect of bodies in motion, from temporary suspension. But both are asking: how do we come together? What kinds of spaces allow for resonance, for the slow metabolizing of our moment? And what happens if we lose them?

Whether through sculpture, sound, breath, or algorithm, I’m trying to create thresholds—zones where the gallery and the club, the contemplative and the ecstatic, the structured and the emergent can speak to each other. Not as binaries, but as intertwined conditions of cultural life.

Abbas Zahedi. Photo: Constantine Spence

Abbas Zahedi: Begin Again

Tate Modern

London

January 29, 2025 — January 4, 2026

NOCTURN [03] it’s your turn to be

17 Little Portland Street

London

November 7, 2024 — April 20, 2025

Abbas Zahedi is a London-based artist and poet whose work centres on reciprocity, renewal, social connection, and care. With a background in medicine and training in psychiatry — both as a practitioner and patient — he brings scientific, philosophical, and poetic insights to bear on fixed narratives around art, history, and institutional life.

Selected shows include: Holding a Heart in Artifice, Nottingham Contemporary, Nottingham, 2023, Frieze Artist Award commission, London, 2022; Metatopia 10013, Anonymous Gallery, New York, 2022; The London Open 2022, Whitechapel Gallery, London, 2022; Postwar Modern, Barbican, London, 2022; How To Make A How From A Why?, Fire Station, South London Gallery, 2022, Diaspora Pavilion, Venice Biennale, 2017.

Awards include: Stanley Picker Fellowship, 2024; Artangel: Making Time, 2023; Paul Hamlyn Foundation Awards for Artists, 2021; the Serpentine Galleries’ Support Structures for Support Structures, 2021; Jerwood Arts Bursary (2019).

Zahedi is an associate lecturer at the Royal College of Art, London, and teaches at universities both in the UK and abroad.